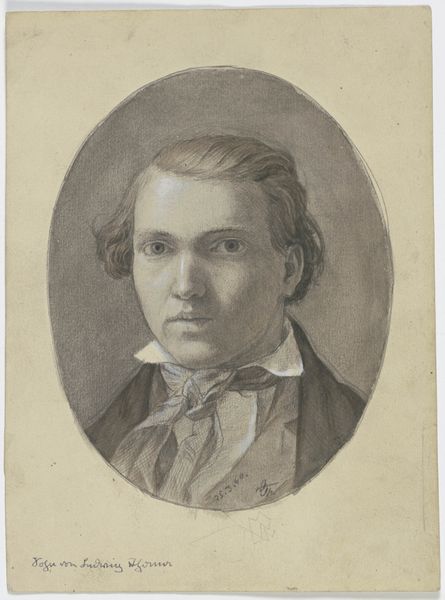

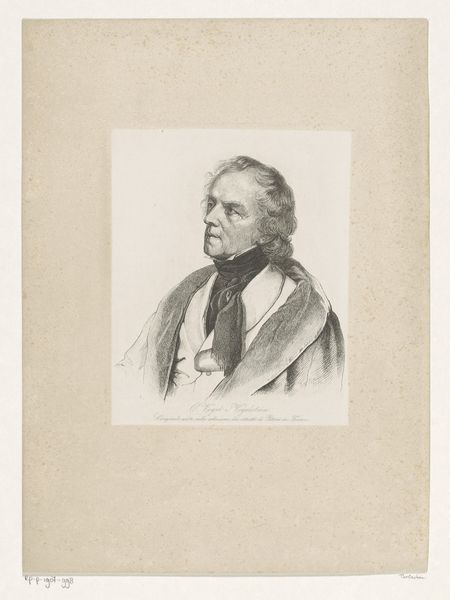

drawing, graphite

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

romanticism

#

graphite

#

portrait drawing

#

academic-art

Copyright: Public Domain

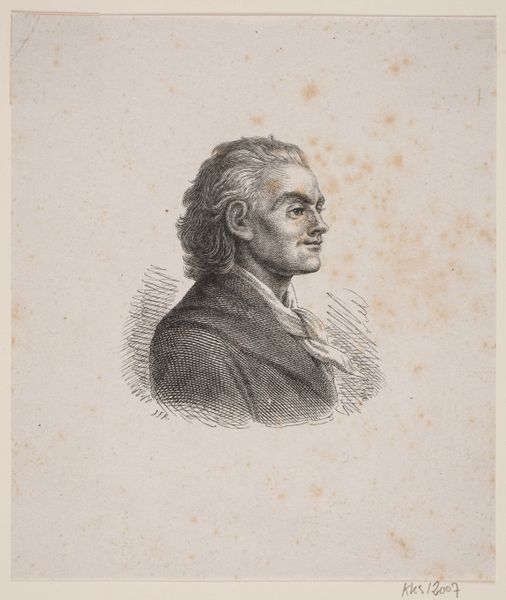

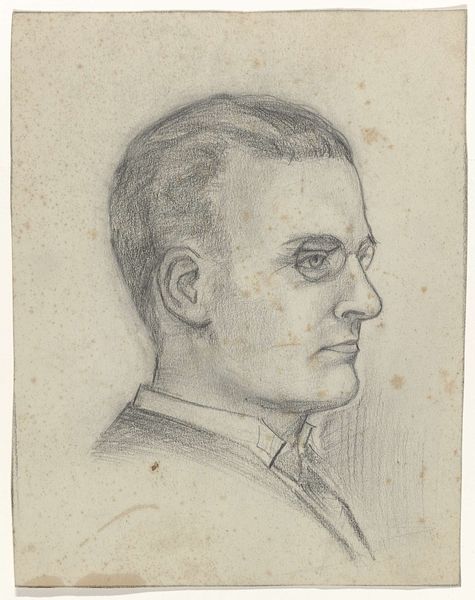

Curator: This is Carl Hoff’s “Portrait of the Frankfurt Clockmaker Johannes Hoff,” rendered in graphite around 1848. It's currently held in the Städel Museum. What strikes you about it? Editor: Well, first, it's quite understated. A straightforward portrait with a serious, almost contemplative mood. The lines are incredibly fine, precise, yet there's a certain warmth, too. I'm curious about the conditions in which it was produced, the paper quality, and the availability of graphite at that time. Curator: Absolutely. Hoff's meticulousness aligns with the Biedermeier aesthetic prevalent in the period. Think about the rise of the middle class; detailed portraiture like this served a new function of solidifying status outside traditional aristocratic circles. This was a new type of social contract. Editor: That’s interesting because, in its depiction of a craftsman, doesn't the work itself elevate labor? By producing such a likeness, is the artist not equally enshrining the importance of the material contributions made by the common worker? It appears the labor of portraiture has aligned itself with, and has become synonymous with, the craftsmanship it is trying to reflect. Curator: A pertinent point. This was Frankfurt at the cusp of industrialisation. Hoff’s piece showcases a fascinating shift. There's a growing interest in depicting individuals not just for their lineage or power, but for their trade, for their role in a developing economy. It subtly challenges the hierarchy within art production as well, acknowledging the sitter's significance beyond mere patronage. The clockmaker and the artist find common ground in producing commodities for the public good. Editor: The clockmaker’s trade, by nature, also intersects with our measurement and understanding of time, an implicit collaboration with history, perhaps? His contribution exists as a form of slow violence against entropy. I can only guess how Johannes’ work would be measured and received by current society in light of a constant desire to quantify human actions as algorithms and big data. Curator: Certainly a resonant notion, and a critical way of thinking. We can consider it alongside the role of the Städel Museum as an institution itself – How does its stewardship today continue to shape, reshape, or potentially obscure the portrait’s intended cultural meanings for modern viewers? Editor: Yes, context continues to evolve. The piece's enduring simplicity is perhaps its greatest strength. Curator: Indeed, providing layers of rich social commentary alongside a tangible understanding of the conditions of labor under which portrait and timepiece were produced.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.