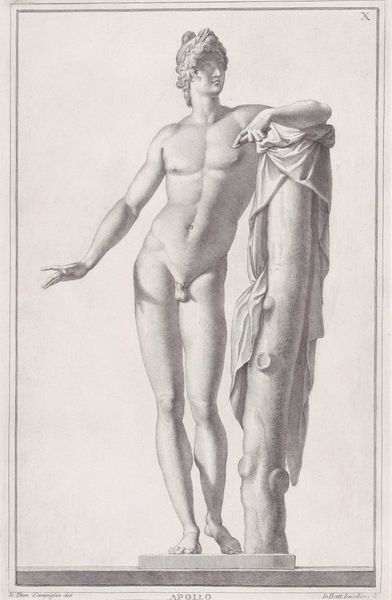

drawing, ink, pencil, engraving

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

baroque

#

pencil sketch

#

figuration

#

ink

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

nude

#

engraving

#

realism

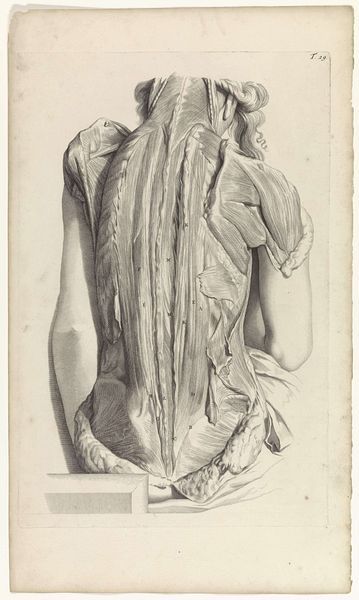

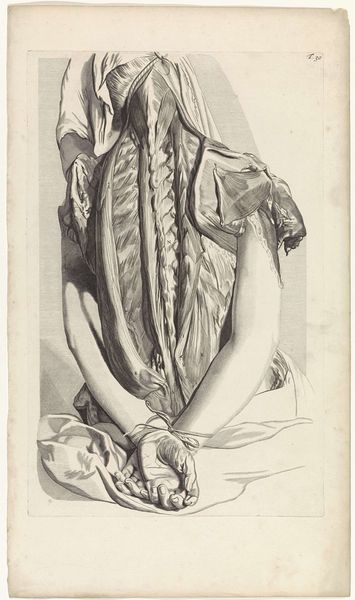

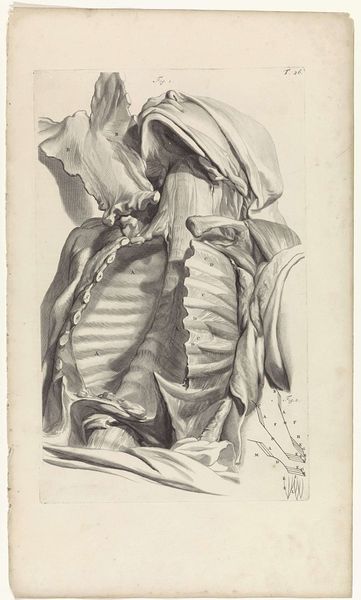

Dimensions: width 274 mm, height 444 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is Pieter van Gunst's "Anatomische studie van de geopende borstkas," from 1685. It’s a pencil, ink, and engraving drawing currently held at the Rijksmuseum. My initial impression is how unsettling yet strangely elegant it is to see the interior of the human chest so meticulously rendered. What’s your interpretation? Curator: The unsettling elegance you describe speaks volumes, particularly when viewed through a critical lens. Think about the context: 17th-century anatomical studies were often shrouded in secrecy, tied to the social power structures of medicine and scientific inquiry which at the time often excluded or marginalized women and people of color from these fields. Who was being studied, and who was doing the studying? What social hierarchies are at play here? Editor: So, beyond the surface-level scientific accuracy, you're suggesting there's a power dynamic embedded in the artwork itself? Curator: Precisely. The gaze, the objectification inherent in dissecting and displaying the body – these actions weren’t neutral. Whose bodies were readily available for study? Often the poor, the incarcerated, the marginalized. Also, notice the draping fabric: how does that contribute to the artist's vision of the body and morality? Editor: I hadn't considered that the body itself may belong to somebody from the margins of society...I wonder, then, how do we look at such an image today, recognizing that complicated history? Curator: By acknowledging that history. By questioning the visual language, the power dynamics, and how they continue to inform our understanding of bodies, science, and art. And crucially, by amplifying marginalized voices and perspectives often missing from these historical narratives. What has struck you most as we explored it further? Editor: Definitely that the drawing becomes more meaningful – more disturbing, and more engaging– when we recognize how intertwined knowledge is with historical power and social justice. Curator: Agreed. Art invites dialogue with the past, yes, but more importantly, to ask, what can it do for us now?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.