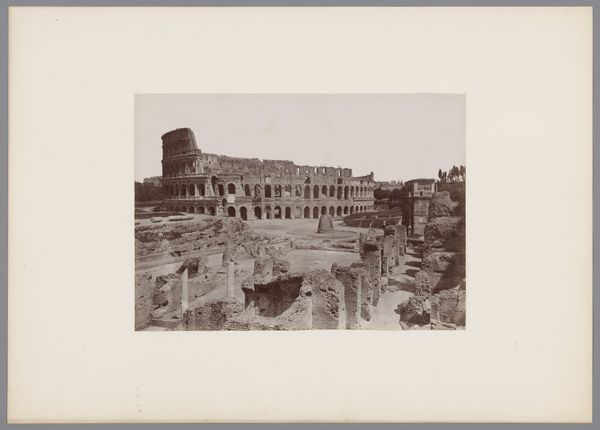

daguerreotype, photography, architecture

#

landscape

#

daguerreotype

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

cityscape

#

architecture

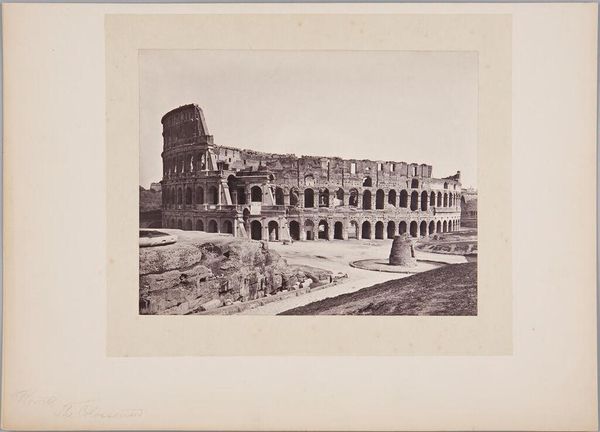

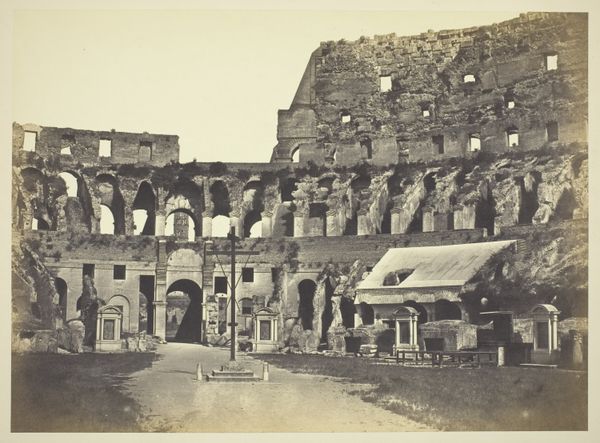

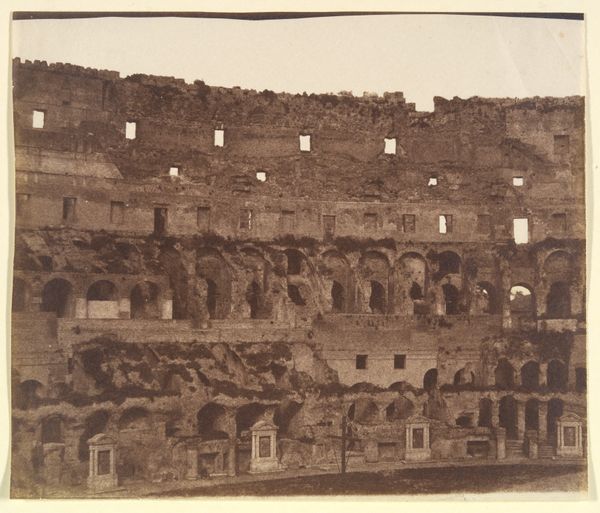

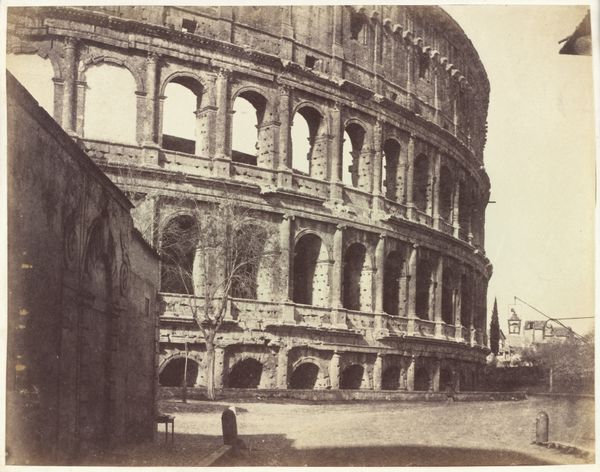

Dimensions: Image: 6 7/16 × 8 11/16 in. (16.3 × 22 cm) Sheet: 12 1/8 × 18 1/2 in. (30.8 × 47 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: This daguerreotype, "Colosseo (Anfiteatro di Flavio)", was captured by Eugène Constant between 1848 and 1852. It's part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art's collection. Editor: It’s strikingly desolate, isn't it? The warm sepia tones give it a ghostly feel, almost as if the Colosseum is a forgotten relic, emerging from the dust. Curator: Indeed. The image acts as a potent symbol of time's relentless march and the grandeur of a fallen empire. The Colosseum's image persists, laden with collective memories of spectacles and power. Editor: I'm immediately drawn to the materiality itself. Look at the crumbling facade, the uneven surfaces of the stone – the daguerreotype perfectly captures the texture, showcasing both the impressive scale of construction and the signs of degradation over centuries. Think about the labor, the quarries, the transportation of the stone… all part of the making of this iconic structure. Curator: That layering of meaning is vital, though. For someone viewing this photograph in the mid-19th century, after waves of neoclassicism, seeing the actual ruin holds powerful resonance. It is a tangible link to the perceived virtues of Roman society but also as a symbol of decline and mortality, issues ever-present in the mind of its public. Editor: Absolutely. But let's also consider Constant’s process: a daguerreotype in the mid-19th century demanded expertise, both in terms of technical and logistical efforts. You needed precise equipment, careful handling of chemicals… Curator: It's intriguing to consider how this image might have been understood differently at the time compared to how we see it today, especially in terms of what it symbolizes. Editor: True, then it was capturing “the real” in a revolutionary way. Now, its age and tones give it its particular atmosphere, making us consider time, work, labor… it becomes its own symbol of a specific historical period in photography. Curator: The visual language remains very poignant today, allowing us to see the intersection of a bygone empire with nascent technologies of image making. Editor: And highlighting the lasting human connection to materials, processes and, inevitably, ruin.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.