painting, watercolor

#

water colours

#

painting

#

asian-art

#

landscape

#

ukiyo-e

#

japan

#

oil painting

#

watercolor

#

watercolour illustration

#

genre-painting

#

watercolor

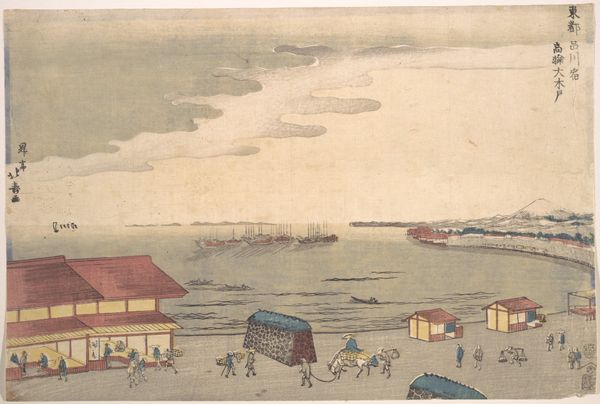

Dimensions: 12 5/8 × 27 3/16 in. (32.07 × 69.06 cm) (sight)

Copyright: Public Domain

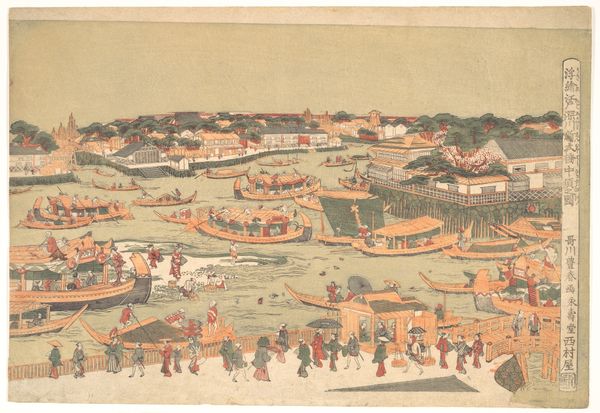

Curator: Look at this evocative genre scene. It's titled "Dutchmen Unloading Cargo at Dejima" and it dates from around the 19th century. The medium appears to be watercolor on paper. Editor: My first thought is of division, starkly visualized. On one side, European ships anchored in the bay, symbols of potential exchange, and on the other, that long, imposing wall of Dejima, a physical barrier and a political one. Curator: Exactly. Dejima was an artificial island specifically created to confine Dutch traders during the Edo period. It represents a carefully controlled site of trade—where the act of unloading those goods becomes deeply symbolic of a monitored interaction. The material reality here is about access and control. Editor: The figures carrying goods emphasize the exploitation inherent in trade relationships. What were the labor conditions of these workers? This image serves as a potent reminder of the inequalities perpetuated by colonial structures, doesn't it? The wall itself is also an emblem of exclusionary policies. Curator: I agree. You can see the artist's meticulous brushstrokes outlining the shapes of goods. Their labor created and maintained these economic pathways; consider the tangible realities involved. Where did those specific goods come from? How did they get here? Editor: It makes me question the narratives of mutual benefit. Who truly benefitted? The vibrant colors of the Dutch ships stand in such contrast to the more subdued palette of the landscape around Dejima, emphasizing the otherness and the carefully regulated position of the Europeans within the tightly controlled Japanese world. Curator: What I find interesting is how the very act of painting itself reflects a sort of labor—translating the seen and experienced world into pigment on paper. This act itself involved the purchase of the pigments, of the brushes, the paper; this is all a material investment. Editor: Absolutely. It highlights how images were complicit in reinforcing specific ideologies of power, creating a visual record of these unequal transactions and solidifying narratives of the colonizer and the colonized. Curator: Yes, thinking about how the materials of art are mobilized for representing economic relations allows me to consider how art serves as a physical reminder and a testament to socio-economic structures. Editor: This artwork encourages us to delve beyond the surface to expose underlying structures of power and acknowledge art as a complex social practice interwoven with histories of colonialism.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

In the sixteenth century, Nagasaki, in far southwestern Japan, was transformed from a remote fishing village into a bustling harbor city frequented by Portuguese, Chinese, and Southeast Asian visitors. A century later, the Tokugawa shogunate designated Nagasaki as one of Japan’s only official international ports. This painting portrays a group of Dutchmen carrying cargo into a walled compound at Dejima, a fan-shaped, artificial island in Nagasaki Bay that served as a trading post reserved for use by Dutch traders until the mid-nineteenth century.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.