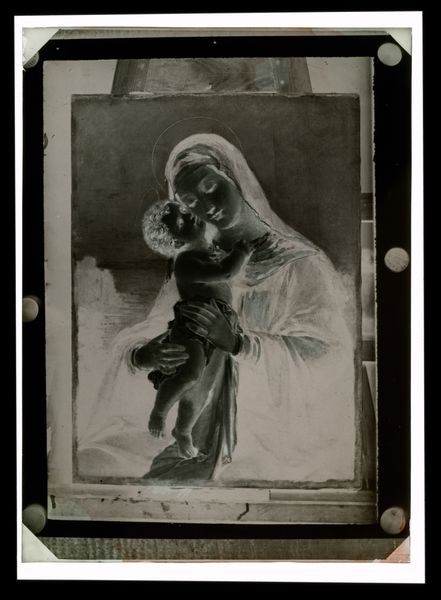

relief, bronze, sculpture

#

portrait

#

art-nouveau

#

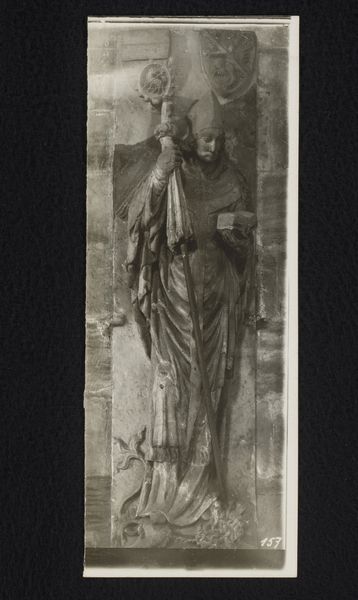

sculpture

#

relief

#

bronze

#

figuration

#

sculpture

#

decorative-art

Dimensions: Overall: 10 × 6 5/8 in. (25.4 × 16.8 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: Before us is Alexandre Charpentier's "Motherhood," created in 1899. The bronze relief is currently held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: It evokes such tenderness. The figures emerge subtly from the bronze; there’s a softness despite the material's inherent rigidity. Curator: Exactly. Charpentier’s work participates in a broader, burgeoning discourse around the fin-de-siècle mother figure—one often steeped in anxieties regarding women's roles and societal expectations, but also reflecting the growing social agency and activism among women in the public sphere. It subtly questions patriarchal structures, too. Editor: Interesting. To me, though, it’s about the physicality, the skilled manipulation of the bronze itself. Look at how the textures vary, creating an almost tactile experience. The draping of the mother’s clothing, contrasted with the smoothness of the child’s skin—it’s a study in materials and labor. Bronze-casting would have been intensely communal in those days too, an art shaped as much by human relationship and expertise as it was individual vision. Curator: I'd like to add that the choice to portray motherhood so intimately, especially at the time, also subtly challenged societal norms. Public art then often glorified war, religion or the wealthy elite. Here is something vulnerable and universal instead, placing importance on maternal labour and the foundational work of women in raising citizens of the republic. Editor: And don't overlook the method: Relief sculptures such as this often featured on the surfaces of ordinary consumer goods like furniture, playing into decorative function over solely high art ones. It underscores how art was intended to enter homes and lives on a granular, quotidian level, thus blurring what we now think of as strictly categorized boundaries between “art” and the wider world of everyday labor and material consumption. Curator: Yes, there is that double perspective, simultaneously pushing back while drawing in and grounding into commonality. This perspective also gives resonance in the way the child finds a resting position within her arms, so calm and still in what must have been tumultuous social times. The work operates both as a sentimental embrace of prevailing concepts of womanhood and a quiet subversion thereof. Editor: For me, thinking about bronze as a material also calls forward connections with craft, skilled labour, and how making art itself entails deeply interwoven practices, far removed from ideals around individual genius alone. Curator: Absolutely. This conversation enriches our understanding by adding new dimensions in looking. Editor: Definitely. Material history is as important as traditional narratives.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.