print, etching

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

etching

#

cityscape

Dimensions: height 80 mm, width 110 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

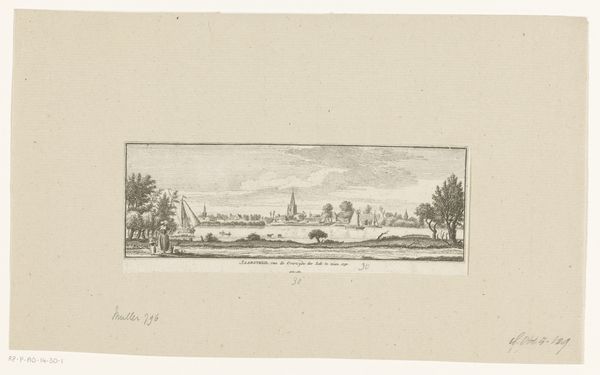

Editor: This etching, "Gezicht op Dordrecht, 1650," by Abraham Rademaker, from between 1725 and 1803, captures a cityscape. The intricate line work gives it a very serene, almost idyllic feel. How do you see it? Curator: The labor involved in producing this print intrigues me. Etching, unlike painting, is an indirect process, involving acid, wax, and intense control over materials. We can appreciate the hand of the artist through the lines he chose, the pressure applied. It’s mass producible, but also intensely individual. Does the labor reflected here tell you anything about Dordrecht at the time? Editor: That’s interesting. I hadn’t thought about it like that. Well, seeing the windmills depicted in such detail makes me consider the importance of wind power, so vital to their economy then. Were there specific social classes benefitting from this etching process and its accessibility? Curator: Certainly. The accessibility of prints fostered a growing art market, benefiting the artist and the print seller, as well as the consuming middle classes, even as the creation relied on other laboring trades for paper, inks, tools and more. And note Rademaker included his signature as a maker's mark, further blurring those lines between artisan, art and craft. Editor: I suppose it prompts questions about who could own art, and who could *make* art. It’s made me consider how something that appears picturesque actually reflects very practical, material conditions of its time. Curator: Exactly. By examining its means of production and consumption, we uncover the hidden socioeconomic narratives. Thanks, that's helped me understand the print better! Editor: Absolutely, thinking about how art gets made definitely changes how I view the finished product.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.