print, intaglio, engraving

#

portrait

# print

#

intaglio

#

figuration

#

italian-renaissance

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 213 mm, width 140 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

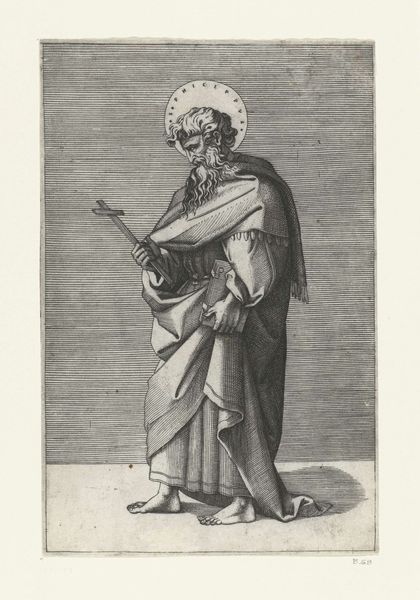

Curator: What strikes me immediately about this print, "Apostel Petrus met sleutels" (Apostle Peter with Keys) by Marcantonio Raimondi, made sometime between 1517 and 1527, is the striking textural variation he's achieved in what is, at heart, an intaglio print. Editor: My first impression is of its severity. It's imposing, almost monumental, despite its small scale, and the lines are incredibly clean and precise. You immediately understand the visual power the Catholic Church would leverage later through dissemination. Curator: Exactly! It’s an engraving, meaning the image is incised into a plate, likely copper, using a burin. Then, ink is forced into those lines, and the surface is wiped clean before being pressed onto paper. Think about the controlled pressure, the angle of the burin to create varied line weights and densities to render the apostle’s robes! The varying levels of pressure required is skillful craftsmanship. Editor: And look at those keys! They practically gleam, dominating the lower half of the image. The keys of Saint Peter are an overt reference to papal authority—to Christ giving Peter, and thus the Church, the keys to Heaven. It's not subtle messaging! Curator: The hatching and cross-hatching—how the artist uses those intersecting lines—creates depth and volume in the drapery and evokes a sense of tactile richness using this intaglio. Considering the labor involved, from preparing the plate to making the final impression, the print wasn't just about artistic expression but also about production, consumption, and how images circulated. Editor: And circulated they did! This image would have served a devotional function, certainly, but also reinforced the Church’s narrative during a period of great religious and social upheaval—the early years of the Reformation! Seeing a piece like this here at the Rijksmuseum encourages contemplation of art as a vital tool in the construction and maintenance of power. Curator: It makes you wonder about the different hands that handled this piece across centuries. Who produced the paper, and what kind of press was used to create the image? How many impressions were made, and how much would one have cost? Editor: This reminds us that artworks aren't just objects of aesthetic appreciation but also complex actors in history, each with a story that impacts its own place within a community. Curator: Precisely! And studying how Raimondi uses such specific tools can also shift how we understand artistry in that particular cultural and political landscape.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.