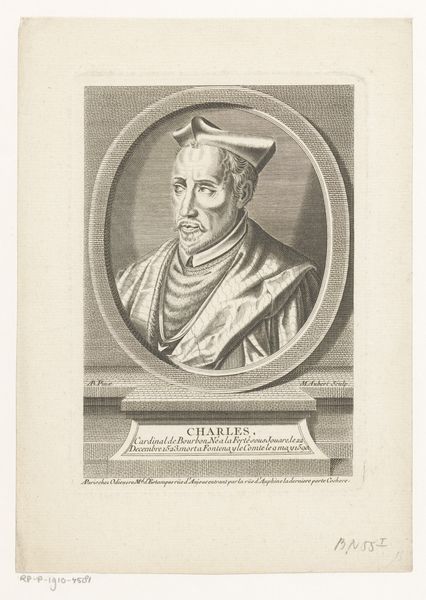

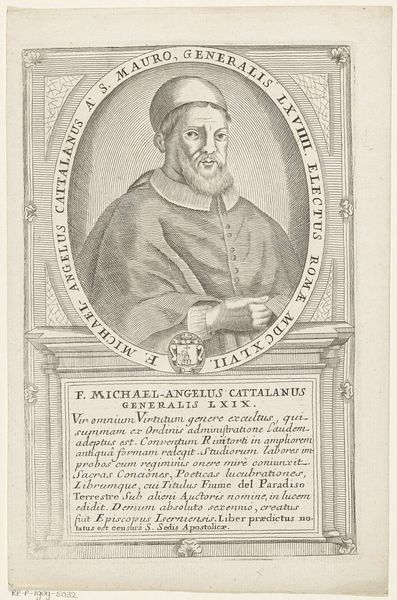

Portret van Miguel Misserotti, 66ste Minister Generaal van de franciscaner orde 1710 - 1738

0:00

0:00

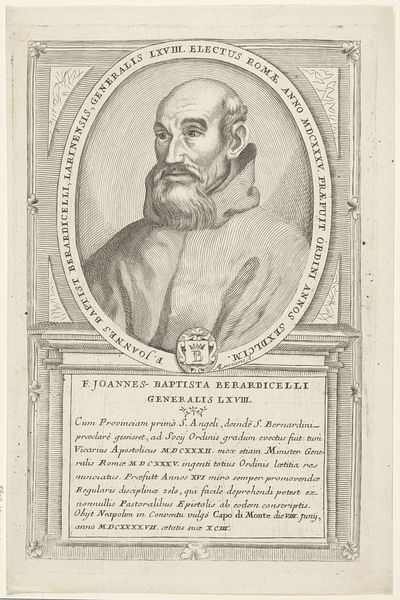

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 248 mm, width 163 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This engraving presents a portrait of Miguel Masserotti, 66th Minister General of the Franciscan Order. It's dated sometime between 1710 and 1738 and made by Antonio Luciani. Editor: The overwhelming feeling I get is…institutional. Everything seems so tightly controlled in its representation, from the stiff pose to the meticulously etched lines of his robes. What exactly do you think it's made from? Curator: It's a print, so we’re looking at the mechanical reproduction and distribution of imagery in the service of promoting someone important. The artist would have started with a metal plate, carving the image using various tools and acids, it's all part of a commercial artistic enterprise. Editor: That commercial element really emphasizes the intended audience, then, doesn't it? This isn't just art for art's sake; it's designed to project authority and convey Masserotti's status to a broad viewership. Notice the elaborate cartouche and the Latin text celebrating Masserotti's titles! Curator: Absolutely. Think about the workshops involved. Someone is preparing the printing plate, others pulling prints, distributors getting it into circulation—there's labor connected to the image. Also the use of engraving as a technique – a signifier of prestige and skilled craftwork. Editor: It definitely tells us something about power dynamics and image control during that era. It seems interesting that the written descriptions of Masserotti include not just religious accolades, but reference to "heretics"... what does this artwork do, visually or materially, to assert a counter position? Curator: Well, this image becomes part of a wider visual rhetoric within the Church. You know, similar prints would circulate, building up an image, a brand if you will, aligning him within established structures of power. It speaks of this constant production, constant reproduction and reaffimation, too, of religious doctrine through materiality. Editor: Thinking about it this way opens up the print beyond just a portrait, to thinking of it as evidence. The act of producing this image reflects institutional self-regard and preservation. Curator: Exactly, this kind of analysis shifts our focus from the image alone to considering labor and capital that went into making the portrait available. Editor: This piece gives us such a tangible peek into the processes by which authority was constructed and broadcast in early 18th century religious circles.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.