photography

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

photography

Dimensions: height 99 mm, width 59 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

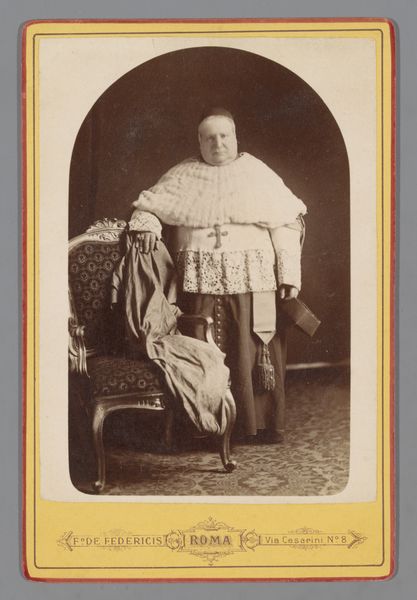

Editor: Here we have a photograph by Bisson Frères, taken between 1852 and 1863, entitled "Portret van Mr. Hamors, pastoor van de Saint-Sulpice te Parijs," which I believe translates to “Portrait of Mr. Hamors, Pastor of Saint-Sulpice in Paris.” There's a real sense of quiet dignity about him. Given that photography was a relatively new medium at the time, what can you tell us about the public's perception of such portraiture? Curator: It’s important to remember how revolutionary photography was becoming at this time. Portraits, once exclusive to the wealthy who could afford painted versions, became far more accessible. Consider the impact on social representation. How do you think this accessibility affected social structures and visibility, particularly for someone like a parish priest? Editor: It democratized the image, didn't it? Making it possible for figures beyond nobility to assert a presence in the visual culture of the era. It feels as though displaying such images in public spaces might cement a degree of trust, wouldn’t you agree? Curator: Precisely. Also, notice the priest's clothing and ornamentation, typical of his era. This wasn’t merely capturing an individual likeness; it was solidifying the church's role as a moral compass in Parisian society, especially following periods of immense social and political turmoil. Consider the Saint-Sulpice itself – it held significant historical and religious importance within the city. Editor: It makes you think about how power structures embed themselves in seemingly simple things like portraiture. Did people actively choose how to represent themselves based on how they wished to impact societal perception? Curator: Undoubtedly. The staging, the props - like the books hinting at erudition, the luxurious shawl denoting his high rank within the church. The Frères were very aware of curating an impression of authority, even within this new medium. The very act of having their portrait taken was a calculated exercise. What are your thoughts on its lasting significance for our understanding of 19th-century France? Editor: I suppose, by studying the visual rhetoric present in portraits like this, we are given tangible insight into the complex dynamic of power, religion, and evolving public representation. Thank you for this interesting approach to portraits; it provides a wider scope to explore!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.