drawing, print, etching

#

drawing

#

baroque

# print

#

etching

#

landscape

#

figuration

#

history-painting

Dimensions: Sheet (trimmed to picture line): 7 1/4 × 5 5/8 in. (18.4 × 14.3 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

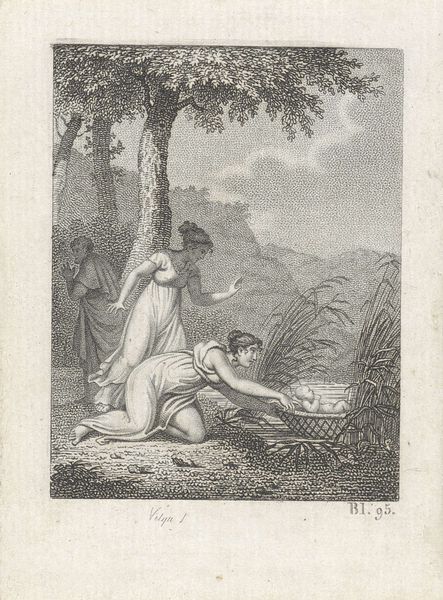

Curator: Here we have "The Temptation of Jesus," an etching by Wenceslaus Hollar, created between 1644 and 1652. It’s part of the collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Editor: That’s a very formal way to meet such a desolate scene. The overall tone hits me as lonely, isolated, and maybe even claustrophobic—and it’s not just the rocky outcrop boxing in Jesus. It’s the oppressive amount of detail filling the scene, an anxious etching… Curator: The density of detail definitely aligns with the anxieties of the period. Hollar, living through the Thirty Years' War, often used his art to reflect the instability and suffering around him. Landscapes, often backdrops in religious scenes, became stages for the drama of human events and faith. Editor: So, even the peaceful river winding into the distant landscape feels troubled because the landscape has always got politics simmering under the surface. But in Hollar’s landscapes, you can read these turbulent times—or try to, anyway. I also find the interaction itself compelling: the tempter pointing, but almost pleading… while Jesus is unmoved. There's something hauntingly familiar. Curator: That's a key element of this moment: the quiet resistance against worldly temptations. The image highlights themes popular in Baroque art during the Counter-Reformation, stressing the importance of moral strength. It's important to remember this print would have circulated widely, influencing beliefs and behaviors during its time. Editor: Yes! In a way, these scenes work in both personal and collective ways. Jesus looks inwardly but does so on behalf of the entire world; while temptation whispers privately in the ear, even as it manifests publicly as worldly glory. It all seems connected, but untouchable. And the contrast with the world makes him all the more… divine? I am just speculating... Curator: And speculating keeps the conversation moving and helps us reimagine the period in question. By examining works such as this, we come to new interpretations, making sure that their meaning resonates across the ages. Editor: Totally, there's no final say with artworks and images like this. I suppose our role now is merely to share these whispers across centuries and add some of our own along the way.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.