engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

#

figuration

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 134 mm, width 88 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

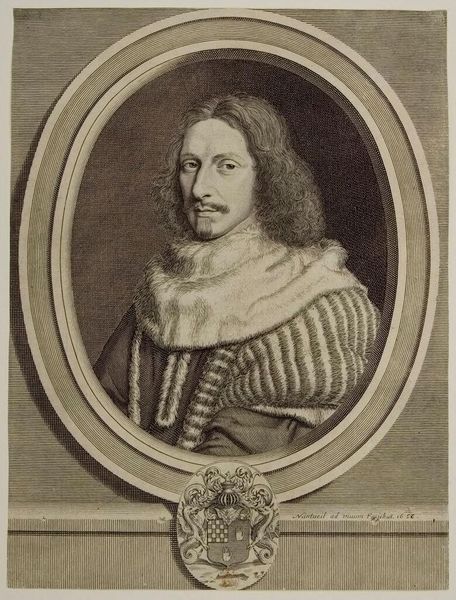

Curator: Oh, he looks intense, doesn't he? This is "Portret van Cornelis van Overstege," an engraving from 1661 by Gerrit Gerritsz van Fenaem. There's something very serious, very still about his expression, isn't there? Editor: Yes, absolutely. The precision of the engraving lends itself to capturing the gravity of the sitter, a sense of the importance this man holds, both in his own eyes and presumably in the eyes of society at the time. The attire reads status; he's very much a figure of authority. Curator: Authority definitely emanates. I find myself wondering about the folds of his cloak, the way light and shadow dance across them. There’s a touch of theatricality there, maybe even a hint of the baroque's flair for the dramatic. But his face is far more reserved than that. Editor: That contrast is interesting. Dutch Golden Age portraiture, though often categorized as baroque, had its own distinct sensibility. This portrait seems to underscore that tension – the baroque's opulence subdued by Dutch pragmatism and a rising merchant class defining new forms of power. Curator: Exactly! You know, there’s something almost secretive in his gaze. Like he’s pondering a solution to a great conundrum or maybe scheming for a competitive advantage. The very detailed style of engraving suits this idea somehow, by showing the world both literally as it appears to the eye and, through art, an intimation of unseen thought and motivation. Editor: The text below his image refers to his “sharp tongue.” I see the intersectional dynamics here: the use of language and the capacity to articulate incisive observations were themselves a source of power during the Dutch Golden Age. Access to education and means to develop that critical, 'sharp' insight became more widespread. To portray him that way acknowledges those cultural shifts in that moment of early modernity. Curator: Well, regardless of his “sharp tongue” – that caption hints at something of a raconteur, almost. Makes one wonder what he’d make of us analyzing him centuries later. Editor: Indeed. Portraits are always fascinating because they're not just representations of people, but documents reflecting shifting social dynamics and ideas around power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.