drawing, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

classical-realism

#

figuration

#

form

#

pencil drawing

#

pencil

#

line

#

portrait drawing

#

academic-art

#

nude

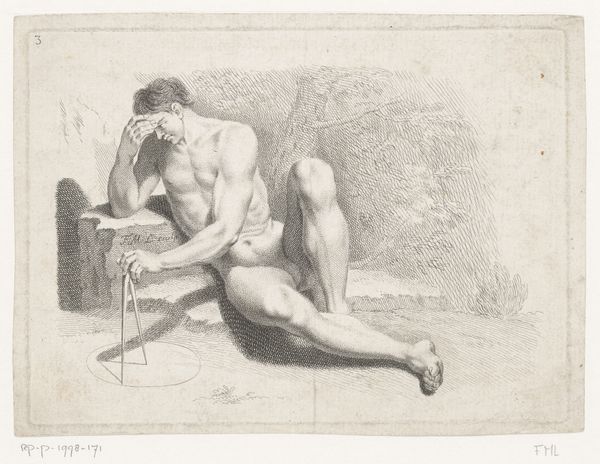

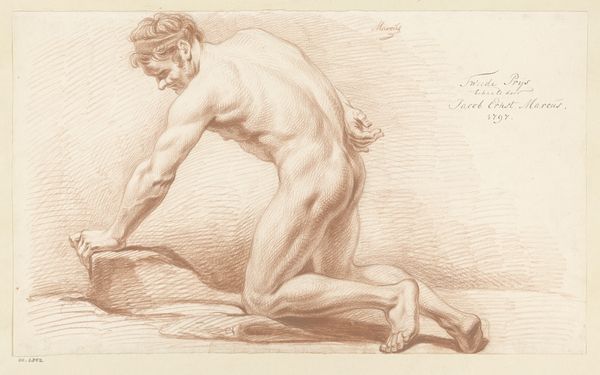

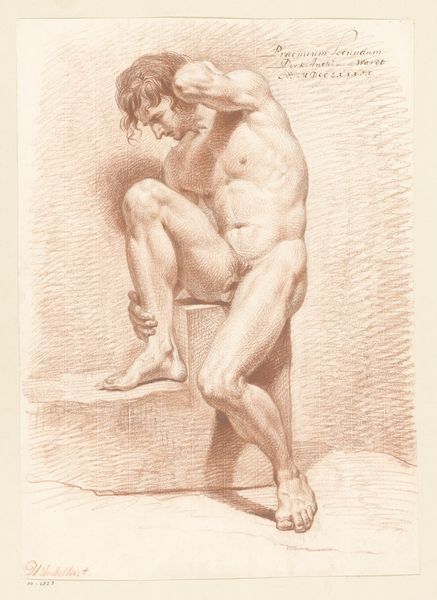

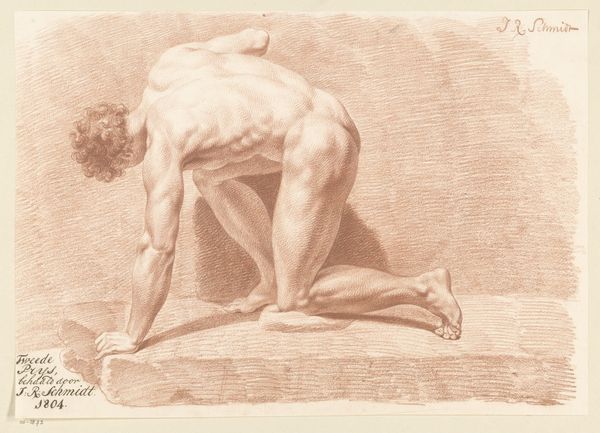

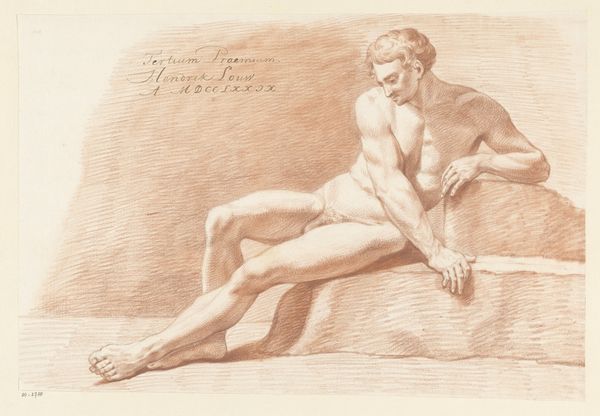

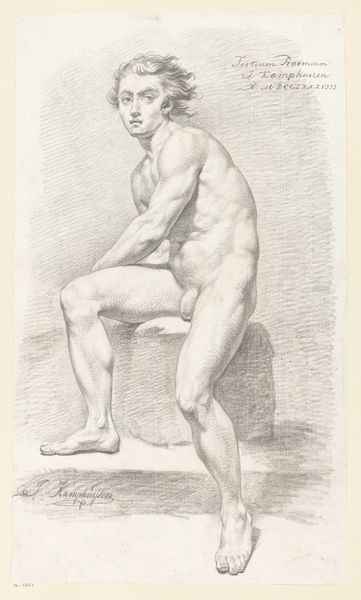

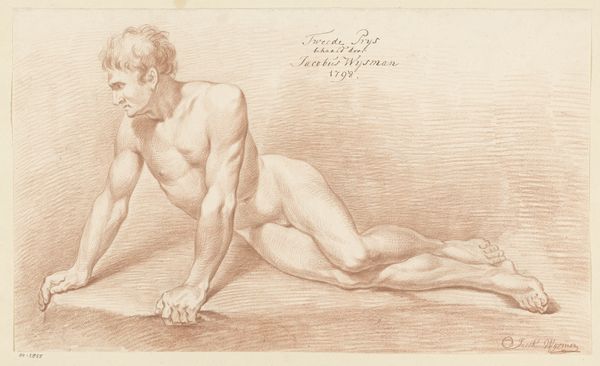

Dimensions: height 340 mm, width 542 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is Arend Alans’ “Zittend mannelijk naakt, van opzij gezien,” or “Seated Male Nude, Seen from the Side,” likely from 1789. It's a pencil drawing and feels so grounded and weighty, in part due to the subject’s pose, the angle of his head, and the presence of that architectural element. How do you interpret this work, especially given the time it was created? Curator: This drawing speaks volumes about the academic structures in place at the time. Note the inscription “3e prijs 1789,” meaning "3rd prize, 1789." It exemplifies the values of academic art—precision, idealized form, and a clear mastery of anatomy, elements often tied to a privileged, patriarchal view. But consider this: who was afforded the opportunity to study the male nude, and who was excluded? Editor: That's a great point. It's easy to see the classical influence and admire the technique, but I hadn’t immediately considered the socio-political dimensions of accessing and depicting the nude figure. Curator: Precisely! The male nude in art has a long and complex history, frequently used to convey power, beauty, and heroism, concepts laden with societal biases. We should examine the context: was this a progressive stance embracing naturalism, or simply reinforcing existing power dynamics? Who was Alans, and what was his position relative to these structures? What narrative might a female artist of the same period have produced? Editor: So, it's important to look beyond the surface and consider whose perspectives are amplified and whose are suppressed. That makes the act of observing the artwork itself a critical one, right? Curator: Absolutely. By interrogating these historical biases, we can gain a more nuanced and critical understanding of both the artwork and the society that produced it. I am drawn to consider its contemporary echoes: How do current social inequalities and power imbalances influence artistic creation and appreciation today? Editor: This has really opened my eyes. I’ll never look at another classical nude without considering the larger social and historical context. Curator: Wonderful! I learned something myself through this conversation. Let's continue thinking about who holds the power to create, depict, and interpret art throughout history.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.