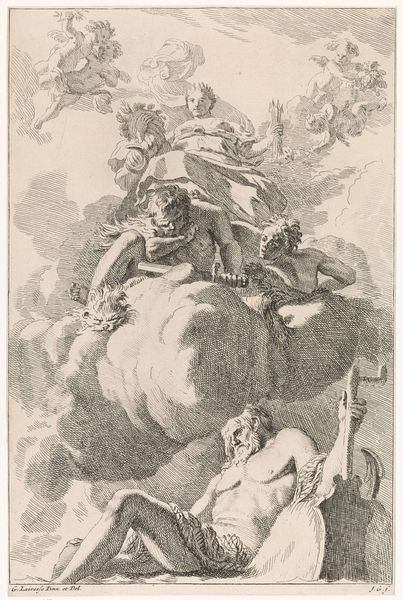

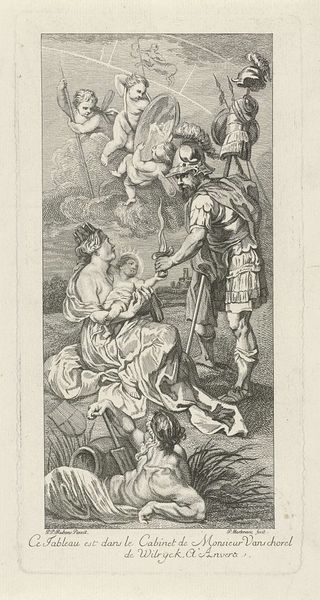

engraving

#

allegory

#

baroque

#

classical-realism

#

figuration

#

line

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Dimensions: width 141 mm, height 391 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This is Valentin Lefebvre's engraving, "Juno schenkt de kroon van de doge aan Venetië," made in 1682. A fairly grand allegorical subject, wouldn’t you agree? Editor: It’s dramatic, that's certain. The scale and line work emphasize this transfer of power; Juno seems almost burdened by the weight of the crown and Venice has her face tilted heavenward as if beseeching for more gifts to be granted to her. Curator: Indeed. Consider the materiality; Lefebvre created this print after an original painting by Paolo Veronese. The engraving process inherently flattens Veronese's Venetian colorism into stark black and white lines. Editor: But this emphasis on line, achieved through skilled labor, gives us another kind of wealth to appreciate, the craft of engraving itself. How do you interpret the allegorical weight? Venice as the recipient of Juno’s gift? Curator: The iconography positions Venice as heir to divine favor and legitimate rule, specifically referencing its Doge through that ornate crown. Note how Juno is depicted with such flowing drapery, her form nearly dissolves into the celestial sphere. Lefebvre uses that softness to suggest the power that is given, not held by Venice. Editor: The coins dropping between them speak volumes about material power. Considering Venice's dominance in trade during that time, this heavenly crown becomes entwined with earthly commerce. Even the seemingly simple act of distributing largesse through money is loaded with economic meaning. What do you suppose Lefebvre suggests when making it so blatant with falling riches? Curator: That power comes from somewhere. This allegory is designed to illustrate both the divine right of Venice and, perhaps, its obligation to higher ideals. The composition encourages a vertical reading: celestial grace flows into the earthly sphere. Editor: Yes, the arrangement underscores not only Venice’s right to rule but the methods and the divine or ideological basis that are entwined in all the means of production. Fascinating, it’s so much about Venice wanting a place to validate the labor and product through symbolic association to gods that have nothing to do with it. Curator: Indeed. It is interesting how he transformed a painting of great spectacle into something so fundamentally based on structure, even in its lack of coloration and flatness. I think our discussion truly elucidates the work’s interplay between visual aesthetics and conceptual grandeur. Editor: And reminds us that material things—crowns, coins, even engravings—always exist in a network of social relations and labor processes. An excellent analysis.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.