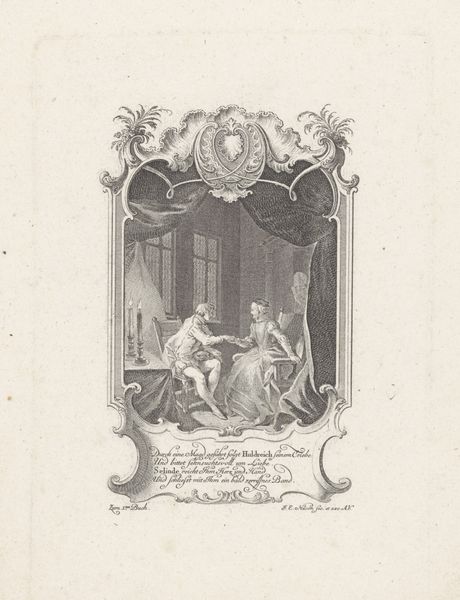

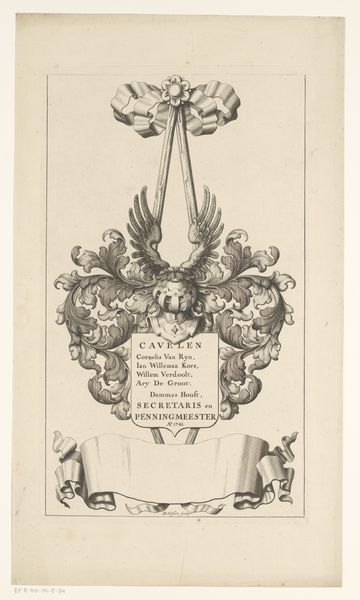

Dimensions: height 265 mm, width 182 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

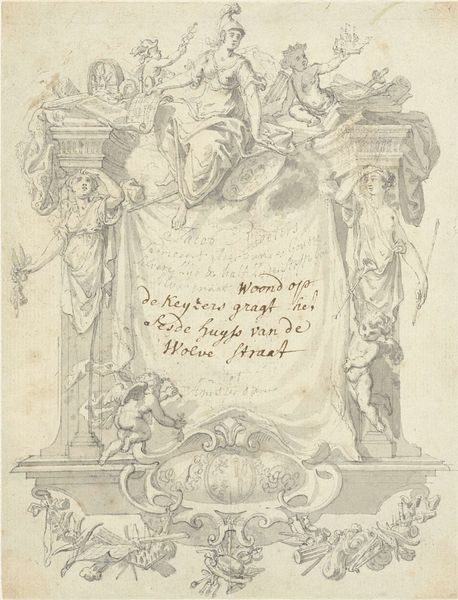

Curator: Welcome. Here we have a print titled "Cartouche met portret J.E. Holzer" made around 1765-1770 by Johann Esaias Nilson. It's currently housed here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: My first thought is how ornate the design is. So many flourishes, swirling lines, and these little cherubic figures give it a really whimsical feel, even though it's a portrait. The linear detail is fantastic. Curator: Indeed. Nilson was known for his decorative prints, and this exemplifies his style perfectly. It's interesting how the allegorical figures – Father Time at the bottom, cherubs around the edges and a bust on top – are framing this portrait dedication, merging the genres of portraiture and symbolic representation. Consider the implications of placing Holzer within such a constructed, almost theatrical space. Editor: Right, it begs the question: Who was this Holzer, and what kind of labor underpinned such an elaborate dedication? Engravings like this were often collaborative efforts. What role did workshops play in churning out such complex designs? I want to understand what this engraving was printed *for* rather than simply admiring its detail. Curator: An important point. These prints circulated amongst a wealthy clientele. It functioned as a means for artists to promote themselves, connecting their name to erudition and the classical past, which brought status in 18th-century European society. Editor: The materials and means of production are also something to keep in mind. The availability and cost of copperplates, inks, and paper dictated who could participate in this kind of artistic production, both as makers and consumers. This print visually presents itself as one thing while potentially concealing inequalities of access and skill involved in bringing such a work to completion. Curator: The Latin inscription, "Ars longa, vita brevis," or "art is long, life is short," highlights the lasting nature of art versus human existence. How would it have affected its initial audience? Editor: Knowing that prints could be endlessly reproduced allows such work to proliferate; considering the social and labor contexts around these types of portrait pieces helps in better understanding it as an artwork. Curator: Absolutely. These prints offered artists and patrons a vehicle for claiming their place within a wider historical and cultural narrative. Editor: Viewing these works with all considerations—both their immediate sensory details as well as the material realities from which they were forged and exist—reveals new interpretations of the artist's work.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.