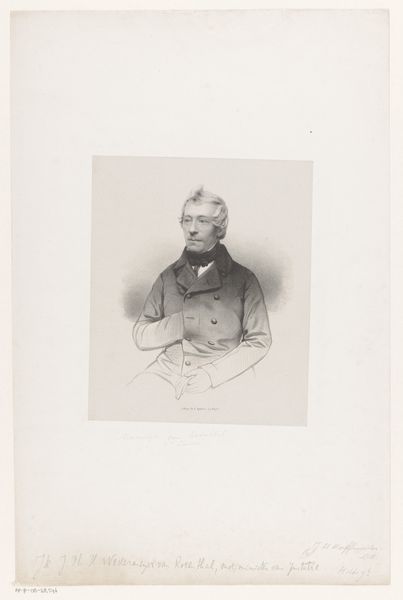

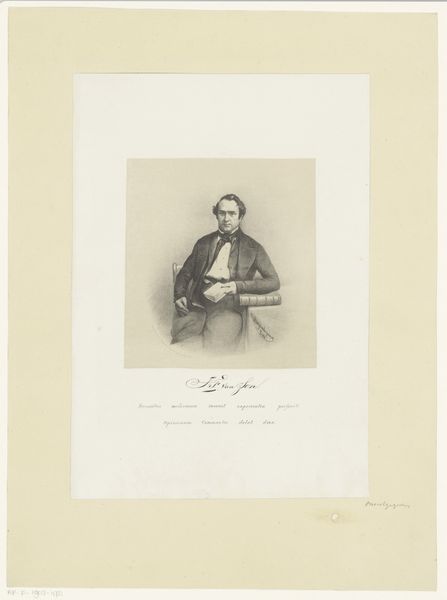

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

aged paper

#

toned paper

#

light pencil work

# print

#

academic-art

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 447 mm, width 312 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is Frederik Hendrik Weissenbruch's "Buste van Johannes Cornelis de Jonge," dating from around 1858 to 1862. It's an engraving, so a print, on what looks like aged paper. The detail achieved with the engraving is quite impressive. How would you interpret this portrait, thinking about the process and materials used? Curator: This piece intrigues me because of its very construction. It's not just an image; it’s an object born from labor. Consider the engraver, meticulously carving into a plate – likely copper, given the period – reversing the image to then be pressed onto paper. That act of reproduction is itself a statement about accessibility and the dispersal of images, shifting from unique object to a commodity. The tonal variations also depend on the engraver's skill, the pressure applied. Does this challenge the hierarchy often imposed between artistic concept and manual skill? Editor: That’s interesting. I hadn’t thought about the social implications of printmaking as challenging hierarchies, I was stuck more in its classical aesthetic! Does the realism tie into that accessibility? Curator: Precisely. Realism, here, isn’t just about visual accuracy, but also about a certain truth-telling achievable through mass production. It is made of humble materials: metal and paper. Do you notice how different it would feel as an oil painting? Editor: Yes, the engraving lends itself to a sort of reproducible authenticity that is intriguing given the social context you explain. I understand better how the meaning lies within both the material and the production process. Curator: Exactly! The material itself communicates something about the changing role of art and its place within society. It's about how art *becomes*, as much as what it depicts.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.