print, photography

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

cityscape

#

academic-art

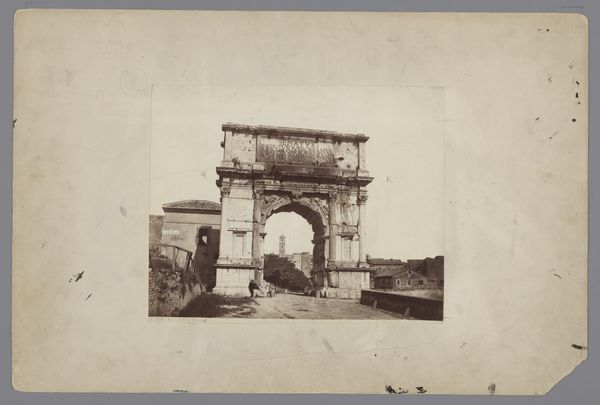

Dimensions: height 253 mm, width 189 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

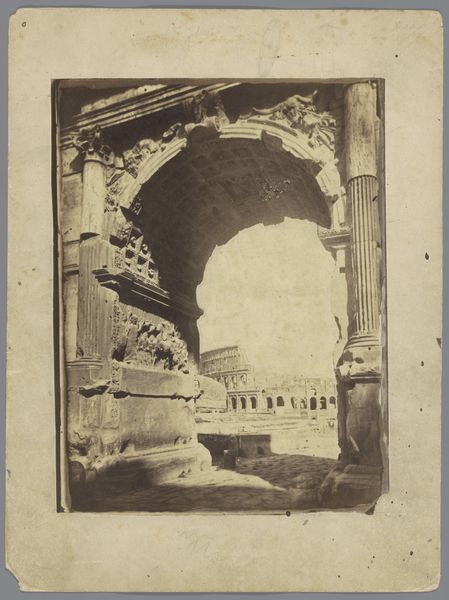

Editor: So, this photograph by Giacomo Brogi, taken between 1870 and 1881, depicts the Arch of Titus in Rome. It's a powerful image, a stoic cityscape frozen in time. What social dynamics might be in play when this photograph was created, and how do they speak to Rome's power then and now? Curator: An interesting question. I'm immediately drawn to considering how photography itself functioned as a tool of power and representation in the 19th century. The act of capturing the Arch of Titus, a symbol of Roman imperial triumph, becomes a way of possessing and disseminating that historical power. Think about who had access to photography at that time, who was controlling the narrative? Editor: That makes sense. So, the choice to photograph this specific monument speaks volumes? Curator: Absolutely. It’s not just a landscape; it's a deliberate framing of history through a specific lens. We have to consider the political context of Italy during this period. The country was in the throes of unification – the Risorgimento – that wanted to lay claim to its Roman past, which becomes this sort of a legitimizing narrative. This imagery helps visualize and popularize that agenda. What do you make of the absence of people in the image? Editor: It almost feels staged, doesn’t it? Like the photographer wanted to present this idealised image of Rome's past, without the messiness of contemporary life. Is it also fair to assume that by framing it in its isolation, there’s almost a glorification of ancient patriarchy, and how it impacts identity and our modern gaze? Curator: That’s insightful. It highlights how even seemingly straightforward documentation is imbued with choices that reflect power dynamics and influence perceptions. Understanding photography, or really any art, as cultural product forces us to constantly interrogate not just *what* we see, but *why* and *how* we're seeing it. Editor: I will definitely keep that in mind when studying historical imageries from now on! Thank you!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.