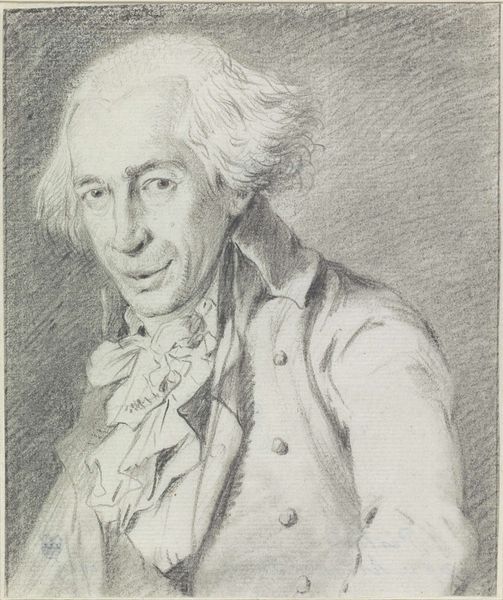

drawing

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

neoclacissism

#

portrait

#

figuration

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

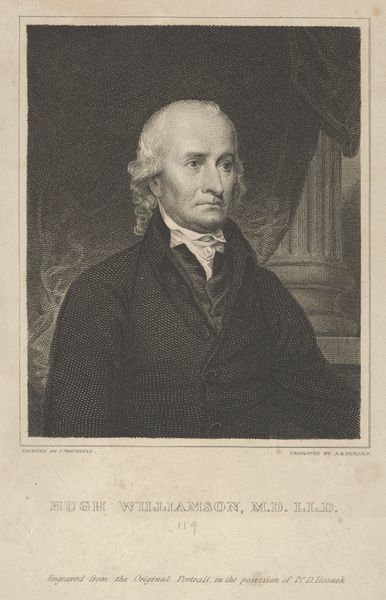

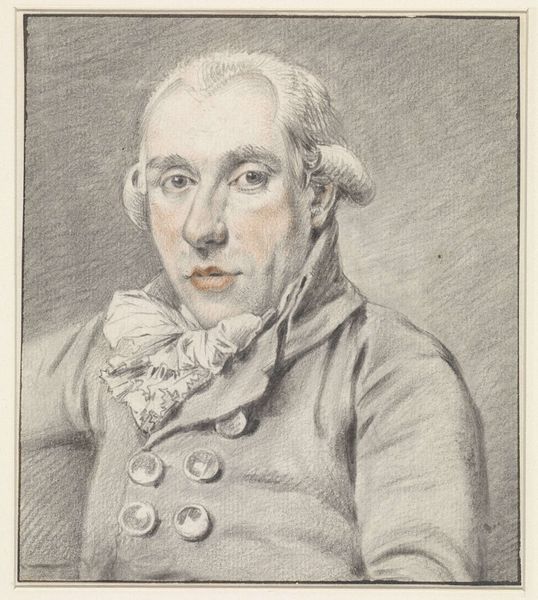

Dimensions: 10 3/4 x 8 1/2 in. (27.31 x 21.59 cm) (image)13 x 10 in. (33.02 x 25.4 cm) (sight)

Copyright: Public Domain

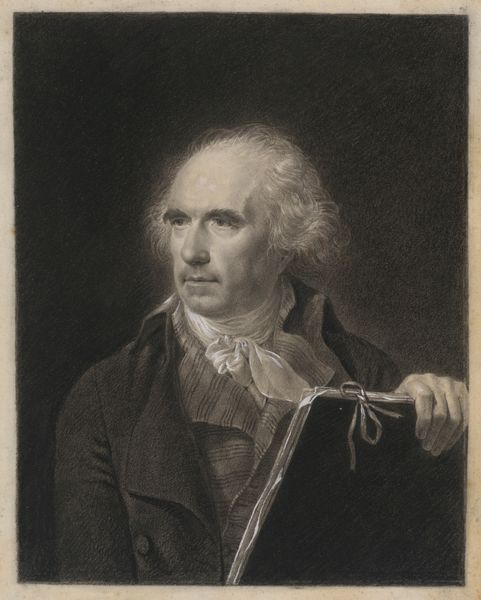

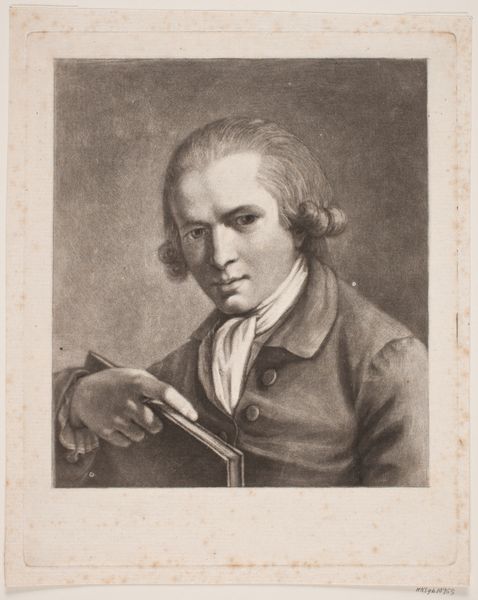

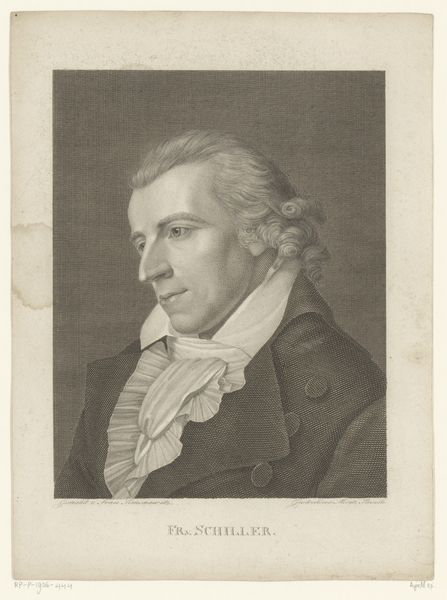

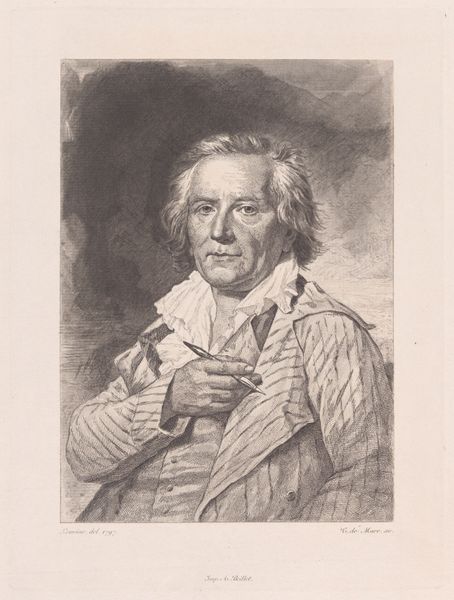

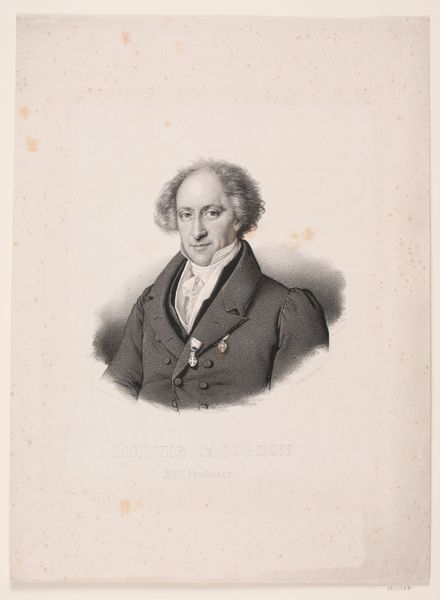

Curator: Editor: Here we have an intriguing drawing, "Portrait of Hubert Robert," created after 1799 by an anonymous artist. It's currently held at the Minneapolis Institute of Art. I’m immediately drawn to the sitter's expression and the soft, almost hazy quality of the drawing. How should we approach our understanding of this artwork? Curator: Considering a materialist perspective, it’s critical to look beyond simply *who* is portrayed, but instead to analyze the means of production. It’s a drawing—what sort of paper? What type of charcoal or graphite allowed for these tonal variations? These decisions speak to available materials, and, in turn, systems of trade. It begs questions: was this drawing commissioned or produced speculatively for sale? Editor: That's a really interesting way to look at it! The artist, and even Robert, participated in material exchanges. Curator: Precisely! Think also of the cultural context. Neoclassicism saw a renewed interest in the handmade object, yet drawings like this were often reproductive – a means of disseminating images more widely. What is the impact of its existence as a drawing instead of painting? What social classes had access to this sort of imagery? Editor: So, it is accessible, in that the materials, paper and drawing tools, were probably less expensive than paints. Curator: And what does it mean that an *anonymous* artist made this? Think about that, it is critical! Editor: I see your point. Focusing on anonymity reveals the means of artistic labor itself. It forces a perspective that moves away from the cult of the artist in favor of broader forces around production and the role of artistic goods. Curator: Indeed! Looking closely at the materials and the process by which they were deployed encourages us to question the societal structures supporting art. Editor: Well, I am beginning to grasp materiality in art history, and thanks for guiding me through it. Curator: The pleasure was mine.

Comments

minneapolisinstituteofart about 2 years ago

⋮

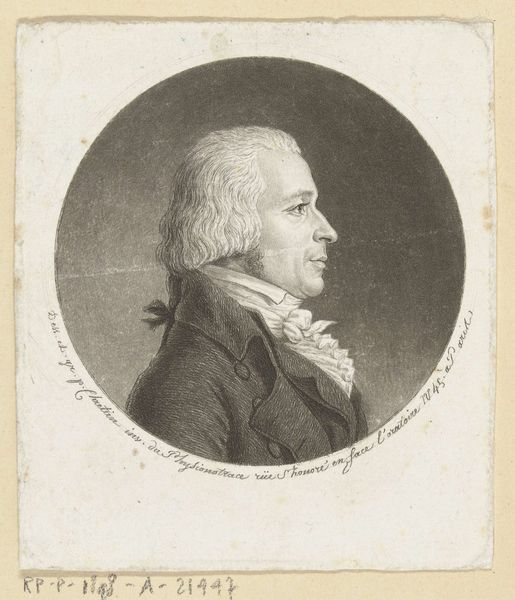

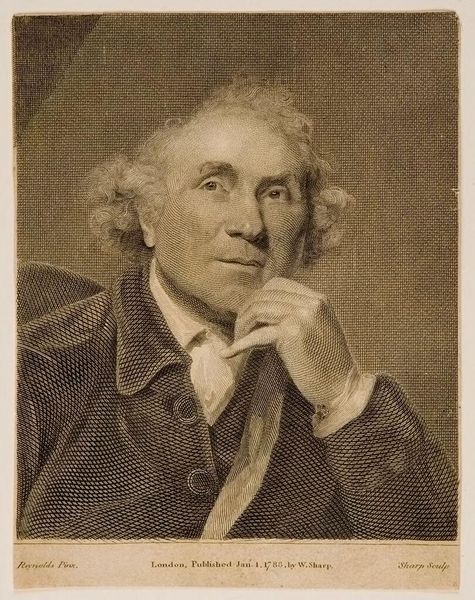

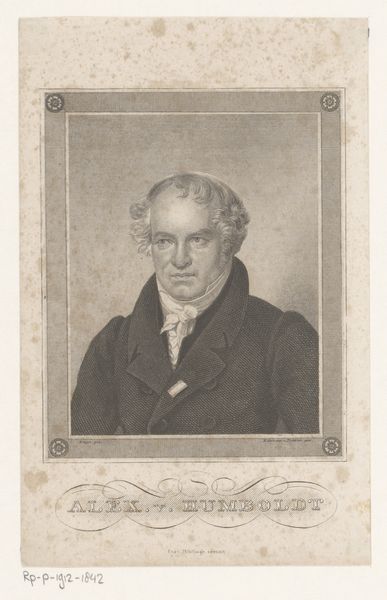

Jean-Baptiste Isabey was the most fashionable miniaturist and portrait painter in France between 1790 and 1830. An intimate friend of Maire-Antoinette and later Napoleon, Isabey also served as painter to the empress Josephine and drawing master to the empress Marie-Louise. Hubert Robert (1733-1808), the subject of the portrait, was an esteemed painter of landscapes and ancient Roman ruins. Young Isabey and Robert were friends, despite their 34-year age difference, and became neighbors right around the time he executed this portrait, as Isabey was granted lodgings at the Louvre probably sometime in 1799. Isabey’s diary makes clear his admiration for the older artist. Isabey's portrait drawing is well known from a 1799 engraving after it by Simon Charles Miger. Many versions of the drawing exist—at least seven can be identified now—and the Minneapolis version was long considered Isabey’s original work. The impressive provenance certainly buttressed its case for priority. But comparison with two other versions of very high quality (NGA, DC and private collection, New York) brought subtle weaknesses in Mia's drawing glaringly to light--namely the eyes, which appear on the verge of going cross, the hand, which lacks weight as does the ribbon tying the portfolio, and the touches of white heightening are purely decorative in the Minneapolis sheet. In Isabey's hand, instead, the white chalk makes the paper and fabric crinkle, and moistens Robert's eyes and lips to appear lifelike. The number of surviving drawings of this portrait is a testament to the polularity of the image, with students copying it and also perhaps collectors requesting drawn copies.

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.