Dimensions: image: 965 x 1919 mm

Copyright: © William Kentridge | CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

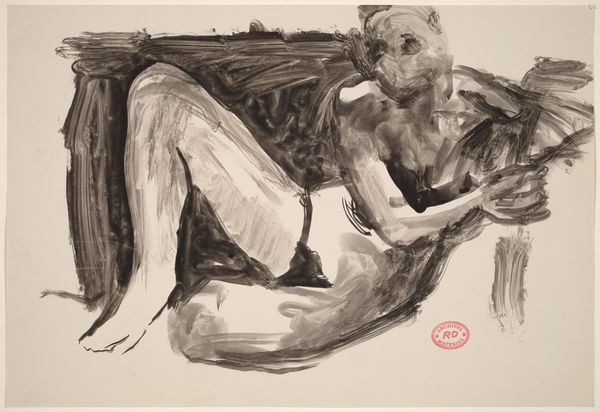

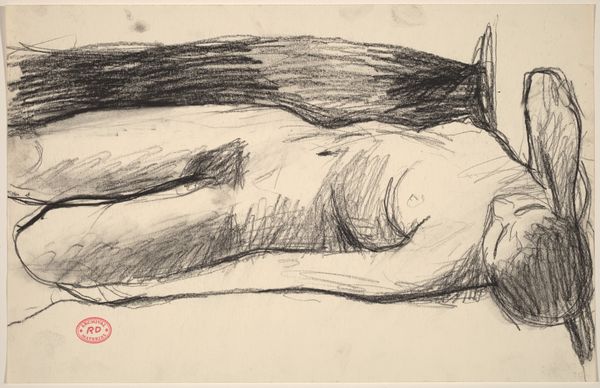

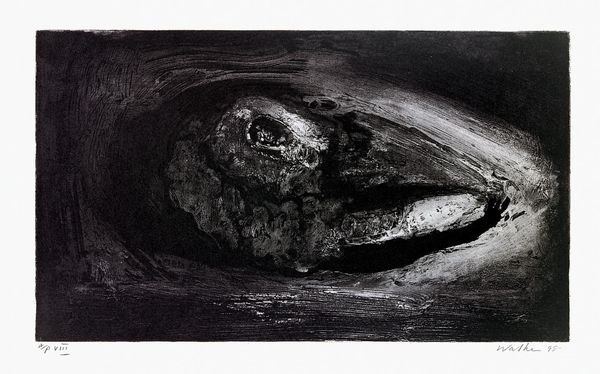

Curator: William Kentridge's Sleeper - Red just exudes a powerful, haunting stillness. It's so raw. Editor: It really is striking. The red background alone, like dried blood, speaks volumes before you even register the figure. Curator: Yes, and the figure itself, stretched out, seemingly vulnerable but also defiant. That pose, almost classical but rendered with such rough, urgent lines. The table, like a stage or a slab… Editor: It reminds me of those pre-Christian funerary effigies, except drained of any hope of afterlife. The face turned away, the limbs heavy. Sleep as oblivion. Curator: Or perhaps a forced rest. Kentridge often wrestles with South Africa's history, doesn't he? Maybe this is a momentary respite from some unnameable struggle. Editor: The pose is not that of a restful sleep. It is more like a dream disturbed by traumatic memories. Curator: Traumatic, yes. But also, maybe, a dream of resistance, etched in the red earth of memory. It’s hard to look away. Editor: Indeed. A haunting vision that lingers.

Comments

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

tate 10 months ago

⋮

Sleeper is an etching produced by the intaglio process in an edition of fifty. It was made at 107 Workshop, near Bath, and published by David Krut, London, during a visit Kentridge made to England. The recumbent naked male figure depicted is very similar to one which appears in a slightly earlier etching, titled Act IV scene 7, from Kentridge's portfolio of eight etchings called Ubu Tells the Truth 1996-7. It is also thematically related to drawings made for his film Ubu Tells the Truth in 1997 (Tate T07481), which was produced in 1997. Kentridge mainly makes short animated films created typically from several large drawings, on which he draws and erases the developments of his narrative. Frequently the films are shown accompanied by the drawings which have gone into their making, providing frozen moments in the history of the film. In his film Ubu Tells the Truth he mixed other media, such as footage from documentaries, photographic stills and moving puppets, with his drawings for the first time. Sleeper, like further series of etchings Kentridge went on to make in the late 1990s, crystallizes some of the major issues of his work. One of Kentridge's fundamental themes is the desire to forget, or to remain oblivious to, difficult and unpleasant aspects of reality and history. More specifically, his films depict the struggle of the white South African psyche with its conscience over the exploitation and abuse of the African land and people, during the period in which the system of apartheid was first challenged and then dismantled. Characters in his films are locked into a state of denial in which preoccupation with personal relationships (such as love affairs) provides a means to ignore the increasingly loud and insistent calls for political change. Sleeping, in Kentridge's work, is a metaphor for a state of blissful ignorance, a return to the internal world of the imagination, which conveniently allows the external world to be forgotten. However, the sleeper must always wake up, at some point, and this moment of awakening and recognition is continually approached in Kentridge's films. It is usually an experience of painful but fertile self-knowlege, in which various types of loss bring the films' Western protagonists to an increased connection to their African landscape and heritage and to their own humanity. Further reading:Dan Cameron, Carolyn Cristov-Barkagiev, J.M. Coetzee, William Kentridge, London 1999Carolyn Cristov-Barkagiev, William Kentridge, exhibition catalogue, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Brussels 1998 Elizabeth Manchester March 2000