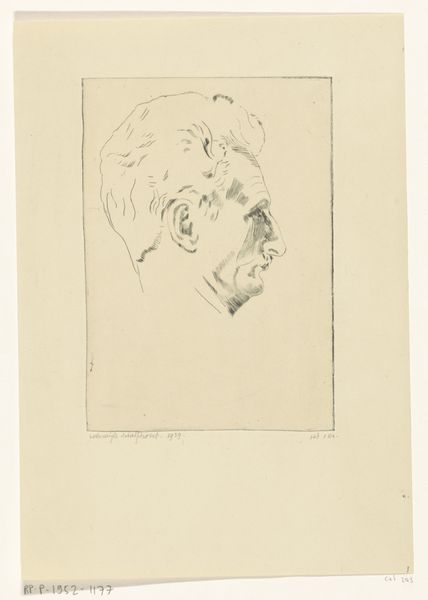

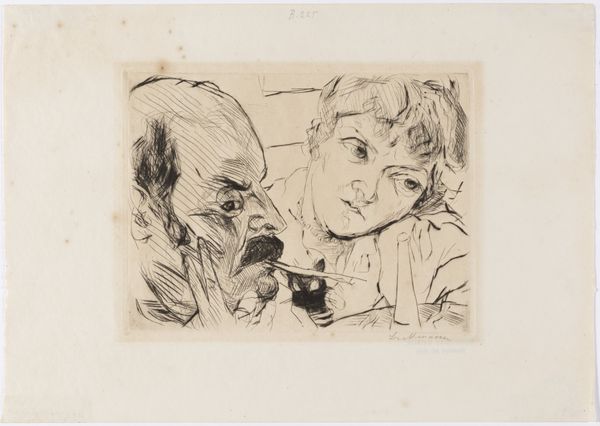

drawing, print, etching, engraving

#

portrait

#

17_20th-century

#

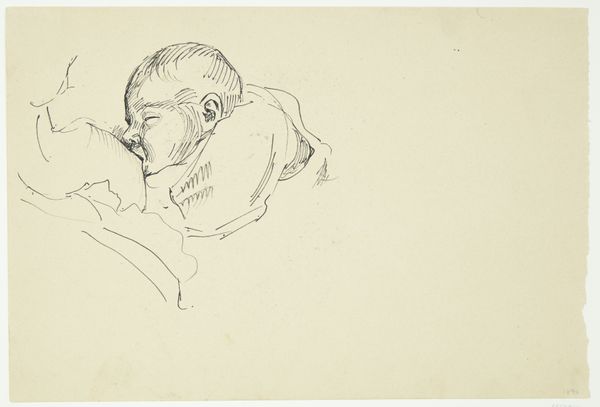

drawing

#

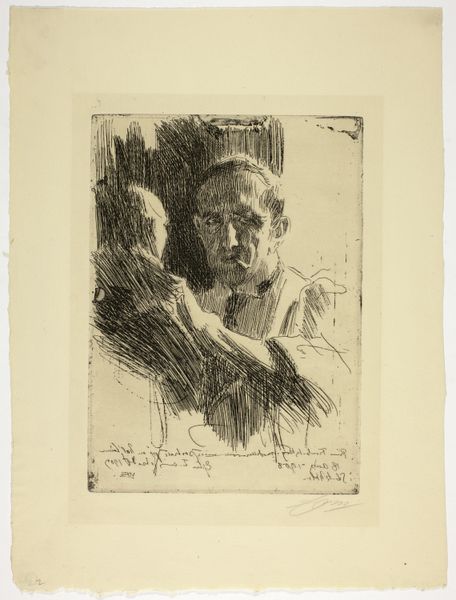

self-portrait

# print

#

pen sketch

#

etching

#

pencil sketch

#

personal sketchbook

#

expressionism

#

engraving

Copyright: Public Domain

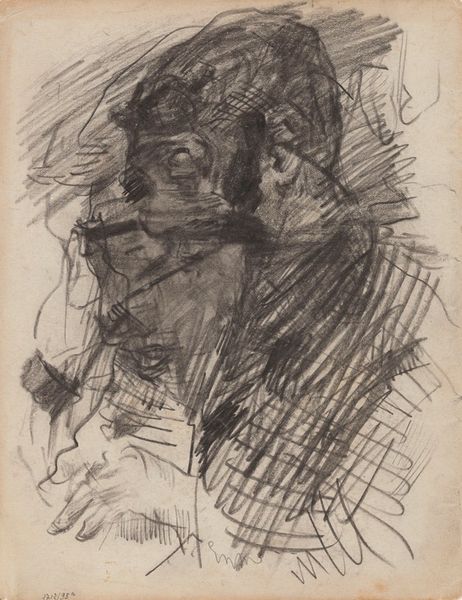

Curator: Let’s discuss Max Beckmann’s "Self-Portrait, Hand to Cheek," created in 1916. It's currently housed at the Städel Museum. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is the stark rawness of the etching. The intense, almost frantic lines feel like they are clawing their way off the paper. It’s immediate and unsettling. Curator: I see that, and I think it resonates powerfully with the historical context. Beckmann created this during World War I, a time of immense societal upheaval. His service as a medical orderly on the front lines exposed him to horrors that deeply affected his worldview, leading to his well-documented depression. This print should not be seen as simply an artistic endeavour, but a profound statement on his psychological condition during a period of societal trauma. Editor: Absolutely, the weight of that experience seems almost physically imprinted on the work. But what’s interesting to me is how the very technique – the harsh etching process – mirrors this psychological burden. The lines, the way the acid bites into the metal, it’s almost a violent process, reflective of the violence experienced by those who participated. The material aspect is vital to its success. Curator: Indeed, and it raises interesting questions about masculinity during wartime. He's not depicting himself in some heroic pose, but rather vulnerable, thoughtful, perhaps even despairing. That challenges traditional notions of masculine stoicism expected at the time. Moreover, this introspection can be seen through a lens of a post-war re-evaluation of men's roles. Editor: Yes, there’s a distinct lack of idealisation. We're not seeing a glorified warrior. It's a raw portrait of a man grappling with internal turmoil, rendered through laborious process. The deliberate use of the etching and engraving techniques reflects the sheer struggle, or 'labor,' necessary to produce an image of the self under such distress. Curator: Precisely. The hand against the cheek can be read as both a gesture of contemplation and of profound weariness, suggesting a deep disillusionment that challenged patriotic narratives of the era. The self-portrait, then, turns into something bigger - a quiet criticism. Editor: Ultimately, it becomes a potent reminder that the tools and materials used by an artist aren’t neutral, they're integral to understanding both the work and the moment in which it was created. Beckmann, in etching his trauma, shows the world it through a visual equivalent to what was happening in society, and within him. Curator: Absolutely, it shows how close and yet, far from these feelings and concepts that, hopefully, most will never feel nor realize. Editor: Agreed, hopefully its ability to engage emotions, without relying on an accurate translation is powerful enough.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.