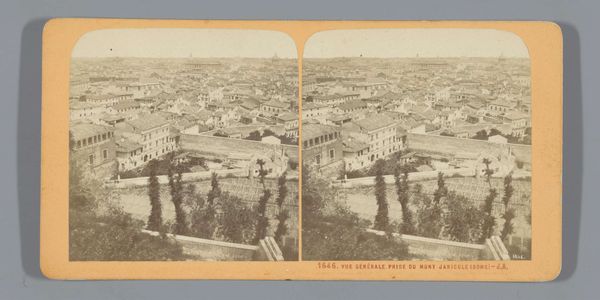

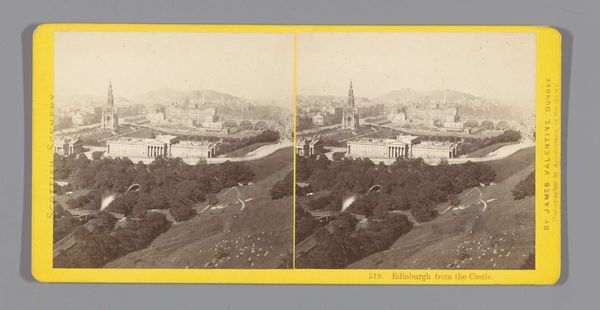

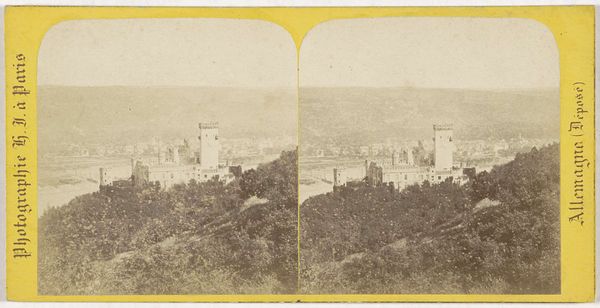

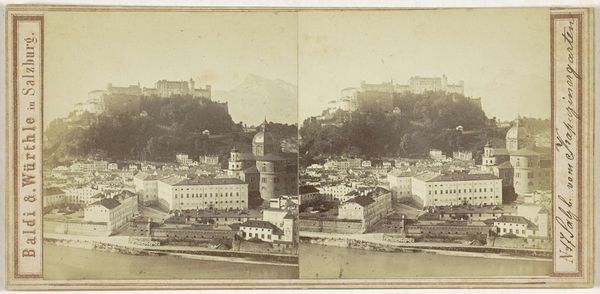

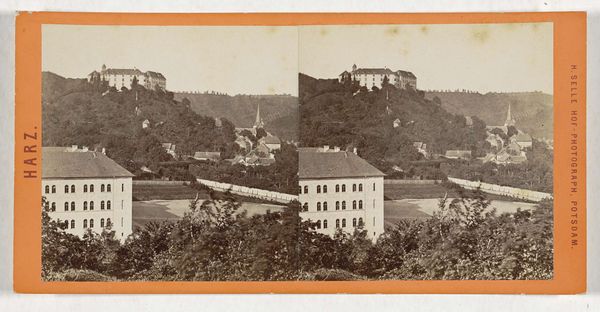

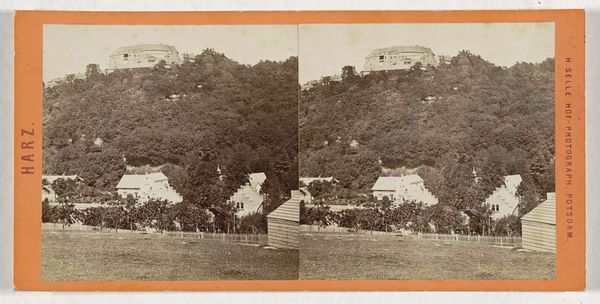

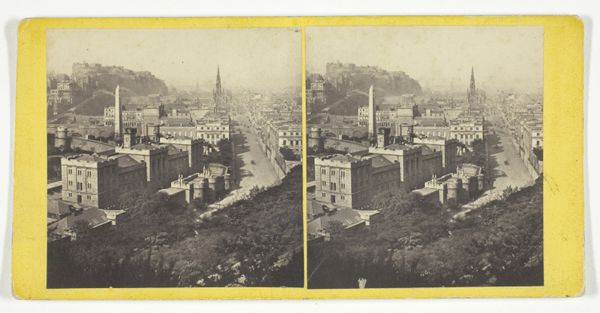

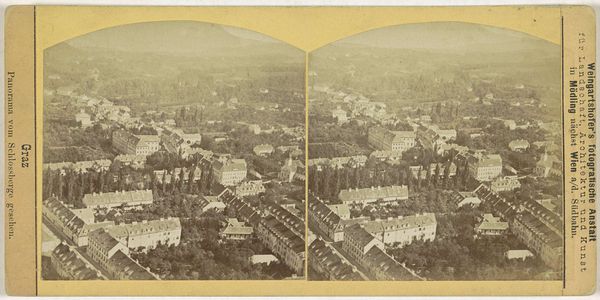

print, photography, albumen-print

# print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

cityscape

#

albumen-print

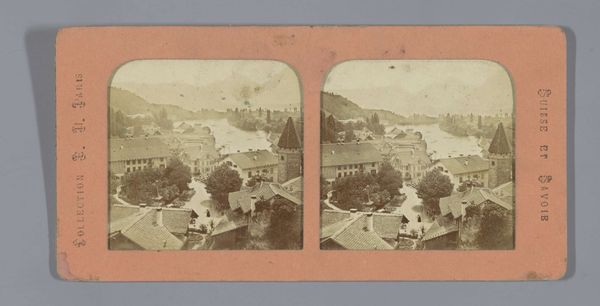

Dimensions: height 84 mm, width 174 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

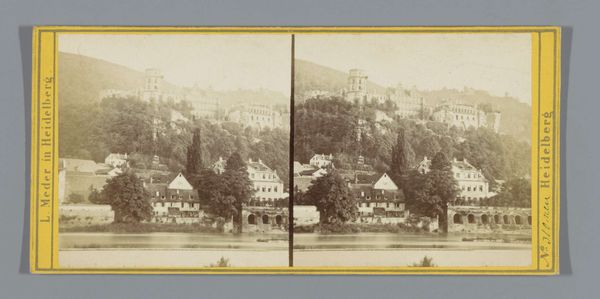

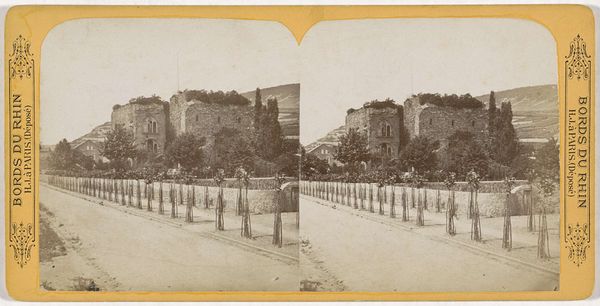

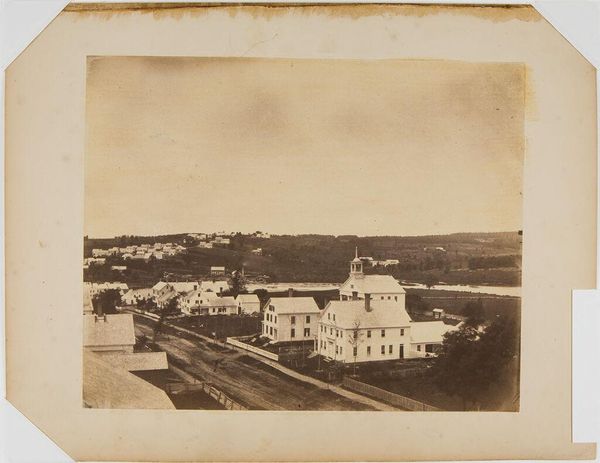

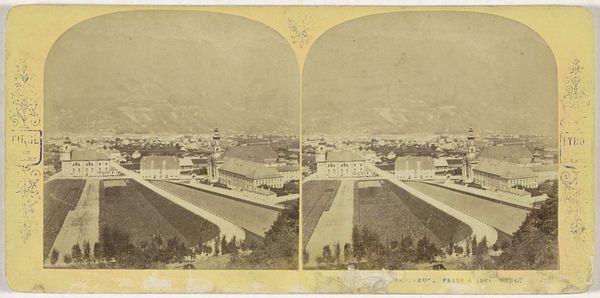

Curator: Here we have “Dolmabahçepaleis in Istanboel,” a photograph dating from 1861 to 1870, attributed to Charles Gaudin. It’s an albumen print presented as a stereoscopic image. Editor: It’s remarkable, this layering of buildings cascading down towards the water. You can almost smell the sea air. The sepia tones give it such a sense of history. Curator: Indeed. What strikes me is how this image captures the burgeoning interest in Istanbul during the Ottoman Empire’s modernization. The Dolmabahçe Palace itself, meant to showcase imperial power, becomes a focal point of European fascination, reproduced here for a stereoscope, bringing faraway places into the Victorian home. Editor: The method of production itself speaks volumes. The albumen print, made from egg whites, demands skilled labor, while the stereoscope hints at a developing culture of mass image consumption. Was it trying to make a foreign land appear real and reachable to average people? Curator: Absolutely, consider the context. This was the height of Orientalism in Western art. Gaudin's image participates in constructing a particular vision of the Ottoman Empire, packaging exoticism for a European audience. Editor: But there's also the materiality to appreciate: the textured quality of the albumen, the way the light catches the architecture. I am curious to understand what this photograph leaves out, regarding who performed the work and under which working conditions. Curator: And who had access to it. How this palace functions in relation to public spaces around it or local life. What sort of politics are going on when it comes to photography and imperial legacy in Europe at the time, that should be our focus. Editor: Both the exoticized vision and the tactile experience are bound by the photographer’s material process and social perspective in Paris. Curator: Quite so. Seeing Gaudin's work from both vantage points offers a more rounded picture. It helps reveal the complex layers that comprise our historical experience and its portrayal through material means.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.