drawing, paper, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

figuration

#

paper

#

11_renaissance

#

pencil

#

genre-painting

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

italian-renaissance

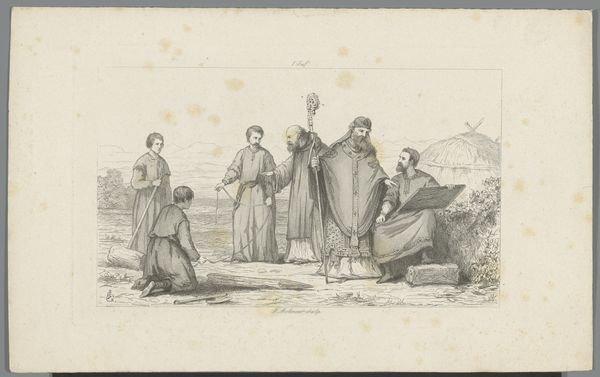

Dimensions: height 365 mm, width 510 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

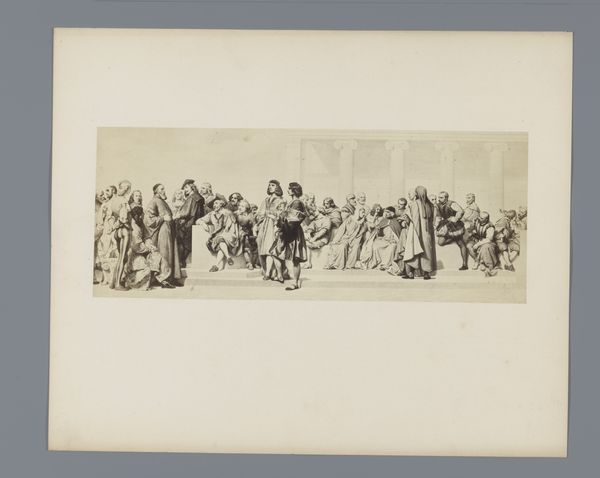

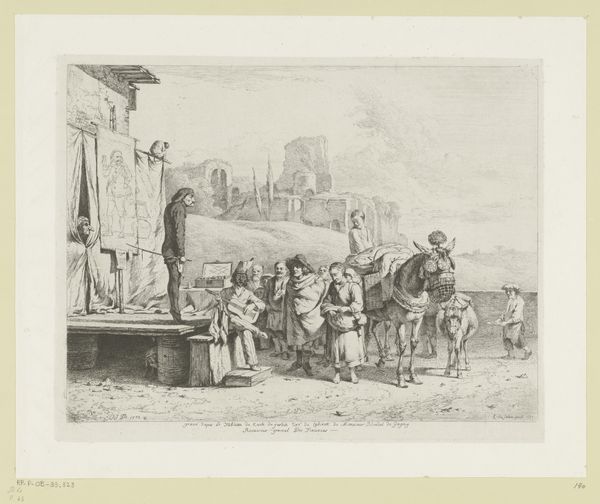

Curator: Okay, so stepping into the realm of historical representation, here we have Wilhelmus Petrus van Geldorp’s drawing from 1873, aptly named "Beeldhouwkunst in de zestiende eeuw"—Sculpture in the Sixteenth Century. It's a pencil on paper piece depicting a rather busy studio scene, buzzing with artistic creation in what looks like the Renaissance period. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is the sense of industry and study – figures clustered around models and statues. Despite the subdued grayscale, it's a lively composition! Are we to understand this drawing as documentation, as a celebration of creative exchange, or what's going on here? Curator: Wilhelmus probably aimed for a nostalgic revival of history painting with his academic style. It evokes a romantic vision of the Italian Renaissance, that golden age, perhaps seen through the lens of nineteenth-century idealism. You have got that almost performative recreation, or rather, his version of a classroom, a meeting. The Renaissance becomes this space for all genders, but especially, a space for men to learn. Editor: Right, so it's both an homage and perhaps an idealized representation of Renaissance workshops, but from a distinctly later, and very different social and political point-of-view. And look at how the black figures stand out as objects for painting practice as a white person paints the figures. This immediately frames questions regarding labor, visibility, and access that weren't universally accessible within that specific timeframe. We see Renaissance practices, and academic ones much later. It seems crucial to explore that relationship... Curator: Yes! It reminds us how art historical depictions are so often loaded with the perspectives of their own time. The figures here aren't just Renaissance artisans; they're filtered through the gaze of 1873. Geldorp is almost reconstructing his past as he sees fit. Editor: Indeed. By showcasing the construction of art, Wilhelmus also gives us a way to reflect on art-making as a constructed discourse, full of gendered power dynamics. But beyond history and representation, this artwork is a reflection on visibility, power, and influence... who gets remembered, whose gaze we prioritize, and what futures we imagine by celebrating this sort of the art. Curator: Absolutely, it adds another layer for us to see. A glimpse, a drawing from paper, back in the day. We need to add other voices to see it completely. Editor: Exactly. Only through recognizing these various angles and limitations can we genuinely learn. And with this historical reflection, we need other pieces from the past, to contrast its views.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.