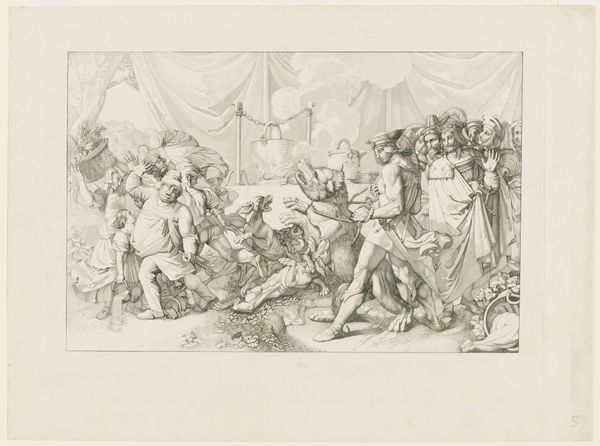

drawing, print, engraving

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

narrative-art

# print

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

line

#

history-painting

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 532 mm, width 657 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: What a flurry of action! Honestly, it's almost dizzying at first glance. Editor: Indeed! We are looking at “The Rape of the Sabine Women” by Pieter Franciscus Martenasie, executed in 1763. This print, employing the linear precision of engraving, throws us right into the chaotic heart of a foundational myth. Curator: "Rape" feels like such a loaded word now for what, mythically speaking, boils down to ancient matchmaking. Look at their faces, though – it’s less terror and more...operatic indignation, maybe? Editor: That indignation, that "operatic" quality, is carefully staged. This isn’t just any brawl; it’s history painting. It aims to ennoble and instruct through classical narratives. Martenasie positions it as a founding moment, the Sabine women destined to be the mothers of Rome. Consider the societal message encoded in this imagery— the role of women, conquest, and nation-building, and the public consumption of the Roman aesthetic, typical of the Neoclassical period in Western European visual culture. Curator: Founding a nation on abduction, though... Ironic how neatly that gets swept under the rug. Visually, I am caught by the composition - figures piled upon figures with incredible line work. Did everyone study that horse in art school? It seems so ubiquitous, rearing and regal. Editor: The horse is practically a genre of its own, an artistic trope denoting power. Martenasie's skill as an engraver, his control of line, that creates movement but also reinforces hierarchy and control, both in subject and in composition. The lines define the subjects for their gendered role within the narrative and create an emotional hierarchy, defining those who lead versus those who follow. Curator: Well, it certainly worked. I still get swept up in the theatrical drama. Editor: I see it too. The work serves a stark reminder. Even images that appear distant in history reflect and reinforce contemporary values and cultural power dynamics. It compels us to ask: Whose stories get told, and how? Curator: Exactly! Art, then and now, is always speaking volumes, even in the silence of black and white lines. Thanks for unpacking all of this with me.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.