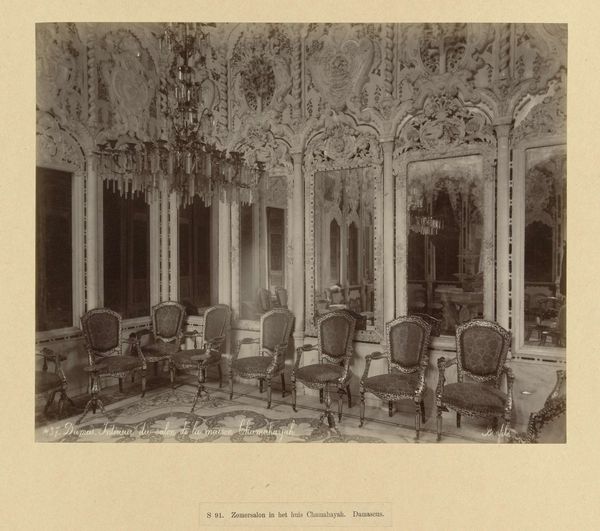

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

orientalism

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

islamic-art

Dimensions: height 222 mm, width 278 mm, height 469 mm, width 558 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

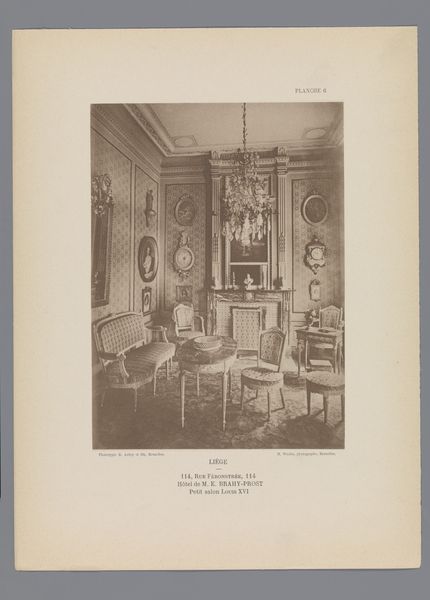

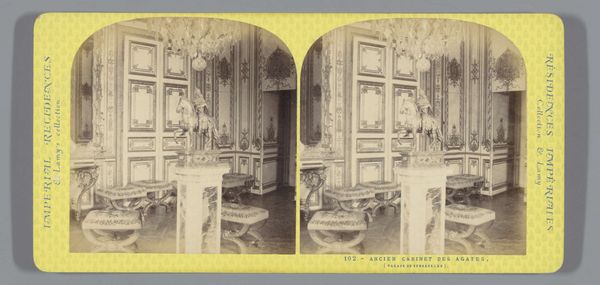

Curator: This gelatin silver print, taken sometime between 1867 and 1877, captures the "Interior of the Chamahayah House, Damascus," by Félix Bonfils. It's a stunning example of Orientalist photography held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: The first thing that strikes me is the material richness. All that marble – you can almost feel the cool, smooth surfaces. The abundance feels…well, performative. Curator: That’s precisely it! Bonfils, like many photographers of his time, presented a vision of the "Orient" that catered to Western expectations. It’s carefully staged to evoke luxury and exoticism. Editor: The meticulous detail in the carvings is compelling; those lion figures supporting the fountain. Who were the artisans? And what was their role in shaping this image for the foreign gaze? Curator: The political context is impossible to ignore. The increased presence of Westerners in the Levant during this period created a demand for images that reinforced notions of power and difference. These photographers became complicit in shaping those perceptions. Editor: Complicit, or canny entrepreneurs? It’s worth thinking about the economics involved: the sourcing of materials, the workshop labor required to create this dazzling interior, and ultimately, the distribution networks that brought images like this back to Europe. This room—itself a site of craft production, really—became subject matter for further material distribution, to new audiences, by photographic means. Curator: Absolutely. And it’s fascinating how the photograph itself, as a mass-produced object, played a part in popularizing a very specific understanding of Islamic art and culture within European society. It cemented orientalist perceptions and prejudices. Editor: Well, and while some view that through a critical lens, maybe others back in Europe felt some form of appreciation. Either way, considering the exploitation involved in making these goods is always a helpful perspective. The image has become almost secondary to its complicated past, which certainly changed the way I'm viewing this photo. Curator: Indeed. Thinking critically about how institutions such as the Rijksmuseum acquired such objects is paramount. It forces us to confront our past, encouraging ethical conversations that lead to a better future.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.