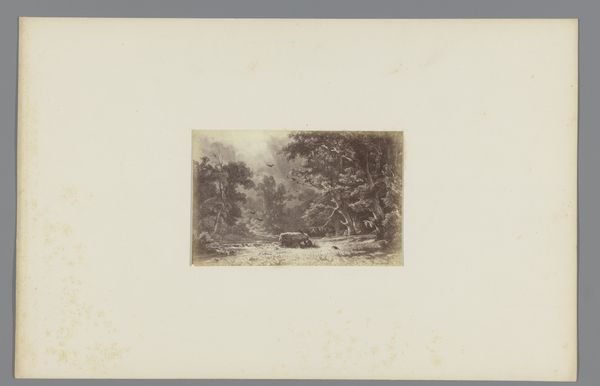

Dimensions: height 222 mm, width 280 mm, height 328 mm, width 399 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: Here we have a gelatin silver print entitled "'Käsegrotte', Bad Bertrich, Rijnland-Palts" from around 1890-1910, attributed to Léon & Lévy. The photograph has this incredibly dreamy, almost staged quality. What are your initial thoughts looking at this landscape? Curator: It’s tempting to simply see it as an idealized vision of nature, neatly framed for bourgeois consumption, a souvenir of a visit to a health spa. But let's think critically. The Romantic era’s obsession with nature was never apolitical. Whose nature are we looking at? Who had access to it? Consider that rapid industrialization at the time forced a lot of people to seek respite and health elsewhere. And who benefited from *that*? Editor: That’s interesting. I hadn't thought about that dynamic. So, you're saying that images like these can mask inequalities? Curator: Exactly. The sublime, untamed wilderness was frequently presented in stark contrast to the industrialized world. This image may encourage that type of sentimentality, obscuring the exploitation inherent to both systems, romanticizing one over the other. Also consider: who took the photograph, and who were they selling it to? Were they part of a colonial enterprise that valued owning images? Editor: So, looking closer, we can read the photograph not just as a picture, but as a cultural object implicated in socio-economic systems of power. Curator: Precisely. The very act of representing nature in this way served specific cultural agendas, impacting our own understanding of both "nature" and "progress". These images, at the time of their making, offered the false belief that these worlds existed independent of one another. What do you take away from that? Editor: I think that unpacking those complexities is important. It encourages a more responsible engagement with images. Thanks for the insights!

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.