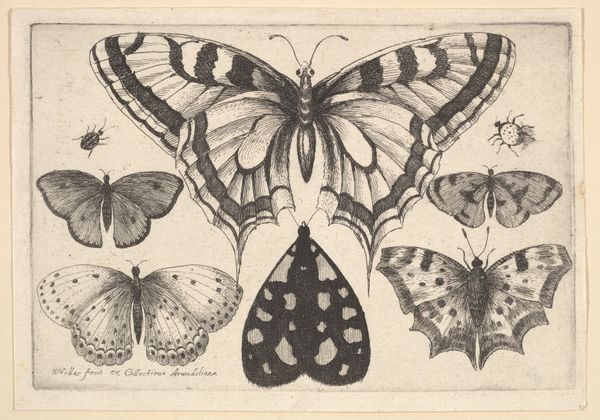

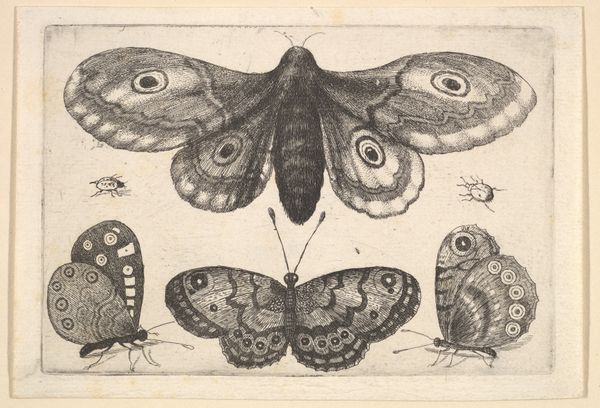

print, engraving

#

animal

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

old engraving style

#

form

#

11_renaissance

#

personal sketchbook

#

line

#

engraving

#

realism

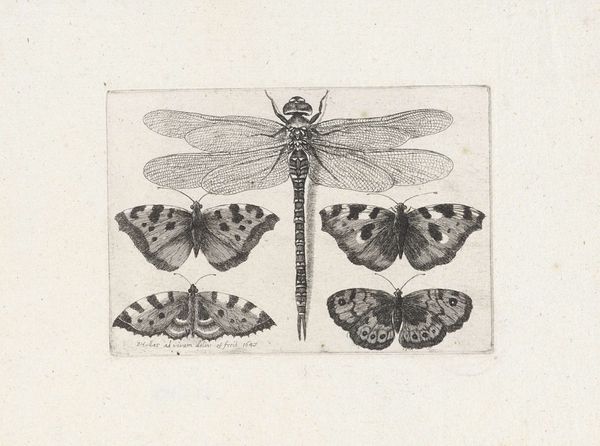

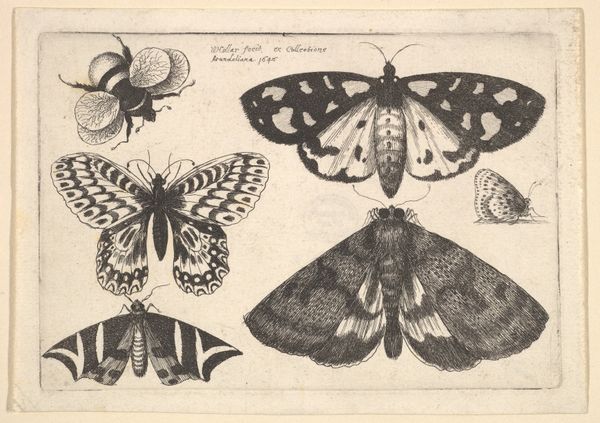

Dimensions: height 79 mm, width 119 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, here we have Wenceslaus Hollar’s "Four Butterflies, a Moth, Two Beetles, and a Fly," made in 1646. It's an engraving, a print, with a lot of focus on realism. The insects feel very accurately observed. I’m struck by how still everything seems. What do you see in this piece? Curator: Beyond the surface of realistic depiction, consider this engraving as a form of early scientific documentation. Hollar's detailed work reflects the 17th-century's burgeoning interest in the natural world, driven by figures like Maria Sibylla Merian. However, access to such scientific study was restricted; how do we understand Hollar's work within the context of gendered knowledge production and societal constraints of the time? Did his prints democratize information, or did they reinforce existing power structures through the lens of a male-dominated scientific gaze? Editor: That's an interesting perspective. I hadn't considered it in terms of power. I was just seeing them as, like, pretty pictures of bugs. Does that connection to science mean we should interpret each insect symbolically? Curator: Symbolism certainly existed. Butterflies, for instance, often represented transformation and the soul. However, within a scientific context, the symbolic readings might have taken a backseat to precise observation. Ask yourself, what does it mean when observation, scientific study, is the realm and the domain of a specific kind of person, mostly European men during this era? Editor: So, the image exists at an intersection of scientific progress, and also of how power dynamics worked then. I suppose, looking closer, I see how even a seemingly neutral image like this can be so embedded in the social context of its time. Curator: Exactly. It encourages us to critically analyze not just *what* is depicted but *who* gets to depict it, and for what purpose.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.