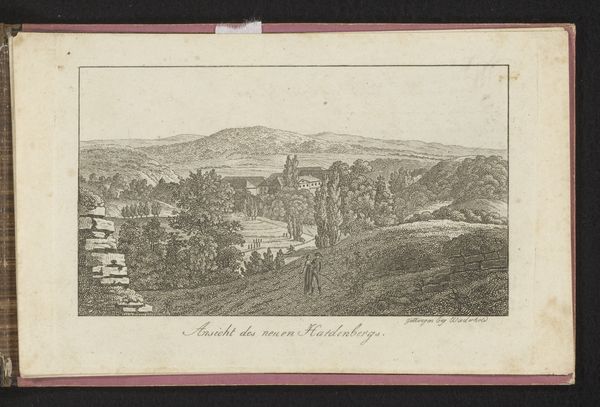

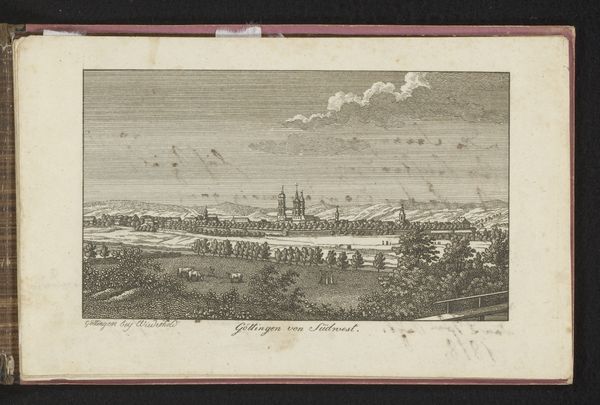

print, engraving

# print

#

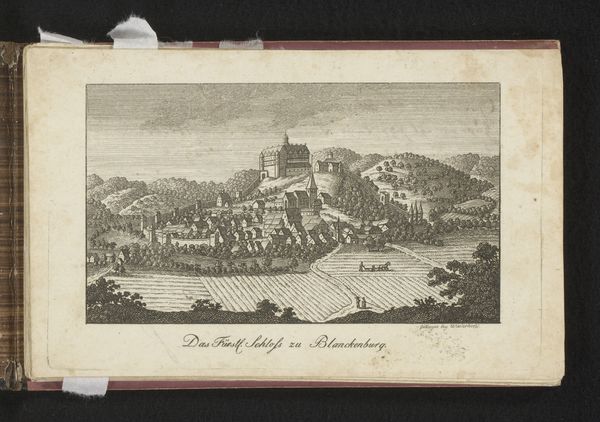

landscape

#

coloured pencil

#

romanticism

#

cityscape

#

engraving

#

realism

Dimensions: height 105 mm, width 171 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: I am drawn in by the tranquility—there is such a stillness in this cityscape. Editor: That’s quite astute. Let me introduce “View of Kiel and the Baltic Sea”, a print dating from possibly 1770 to 1818, made using engraving techniques. Curator: The engraving gives it a delicate, almost fragile quality. The linear detail emphasizes the labor needed to cultivate this landscape—look at the farmers harvesting the field and preparing the wheat. Editor: Indeed, the placement of labor in the foreground immediately historicizes it, placing Kiel within an early industrial and economic framework that supported not just local activities, but global commerce, considering that access to the Baltic Sea supported trade networks and exchange. It reminds us to interrogate traditional divisions and consider the work necessary to shape land and cities. Curator: Absolutely, the texture, both real and implied by the linear perspective, tells a story of transforming land—what materials were used, and to what end? We also get to see a cross section of local professions through its depiction of working life! Editor: Right, by situating working life front and center, it invites reflection on identity and labor practices within a growing Baltic seaport town in the late eighteenth century. How does it capture the tension between tradition and progress? I’m wondering who produced these engravings, for whom, and under what social and economic circumstances? Curator: Excellent questions. Someone was handling copper, engraving the details… how did that production intersect with social hierarchies and labor relations of the time? What tools were available and who had access to those tools? Editor: Exactly. When examining landscapes and cityscapes we also want to see them as reflections of cultural values, power structures and social dynamics. Curator: I’m glad you connected us with the context outside the frame. It truly shows us that no object or landscape exists in isolation, but within systems and histories. Editor: Yes, and seeing its place helps to appreciate art that prompts ongoing examination.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.