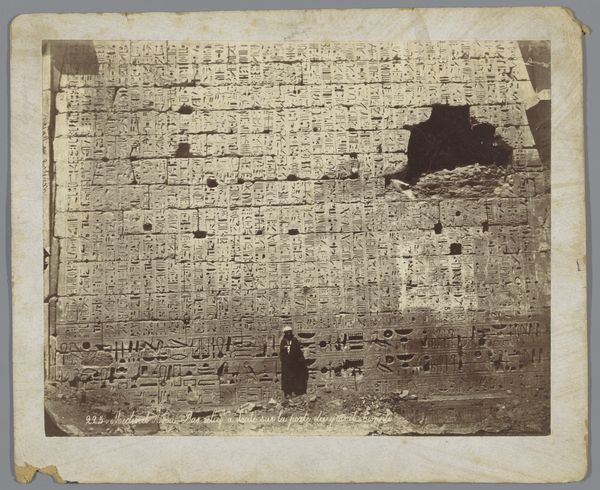

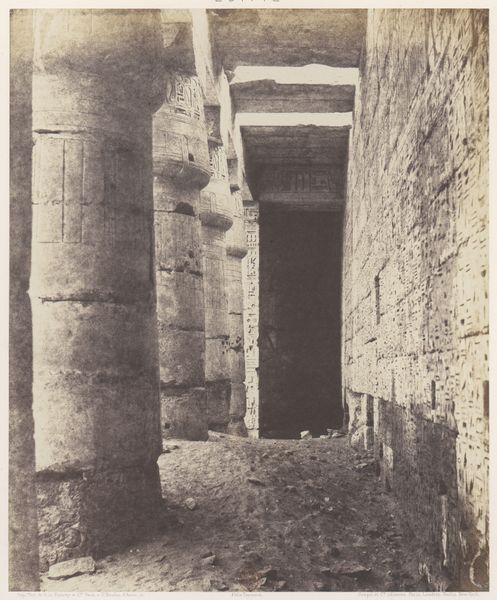

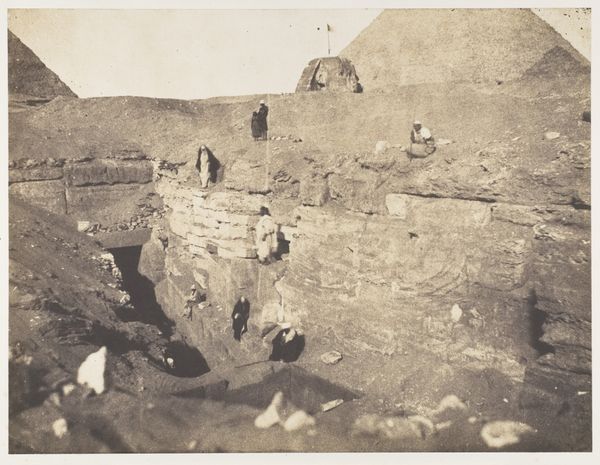

Ile de Fîleh (Philæ), Premier Pylône, Inscription Française Gravée Sur L'Ébrasement Oriental, En M 1851 - 1852

0:00

0:00

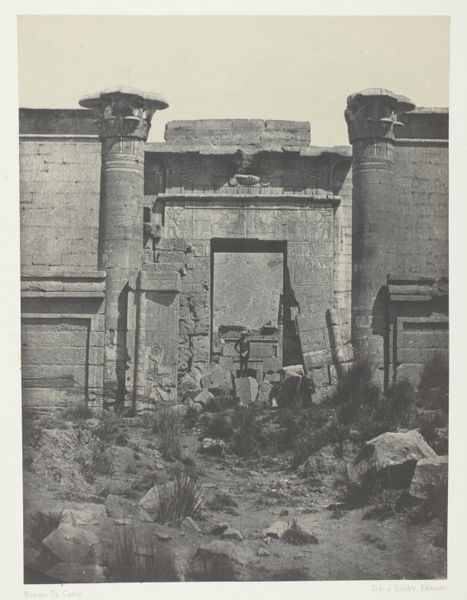

photography, gelatin-silver-print, architecture

#

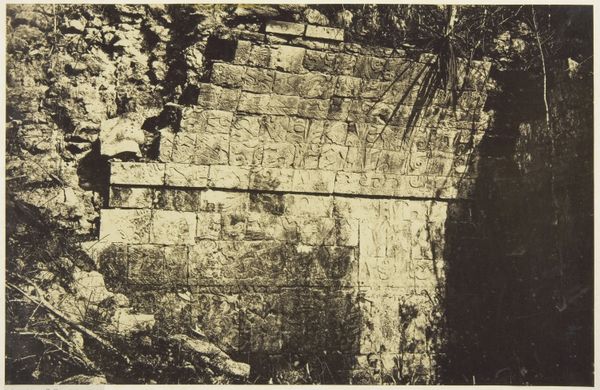

landscape

#

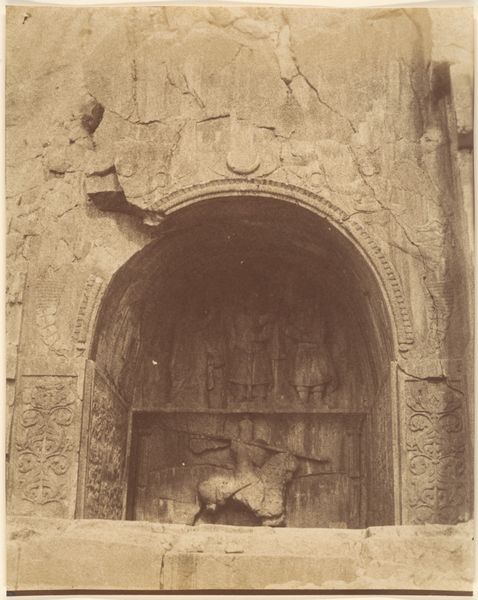

ancient-egyptian-art

#

photography

#

ancient-mediterranean

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

history-painting

#

architecture

#

monochrome

Dimensions: Image: 23.7 x 30.6 cm (9 5/16 x 12 1/16 in.) Mount: 39.9 x 51.7 cm (15 11/16 x 20 3/8 in.)

Copyright: Public Domain

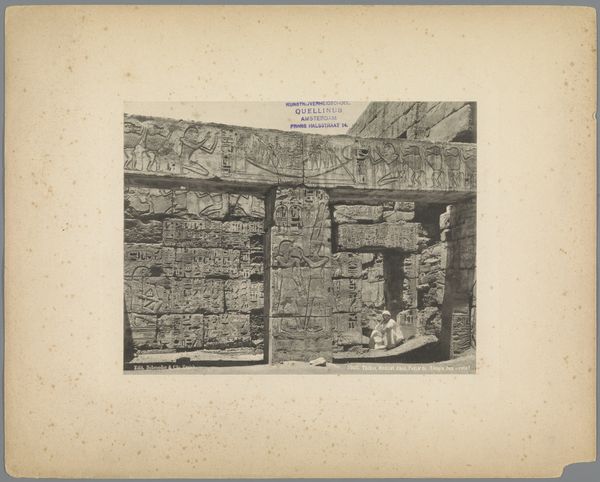

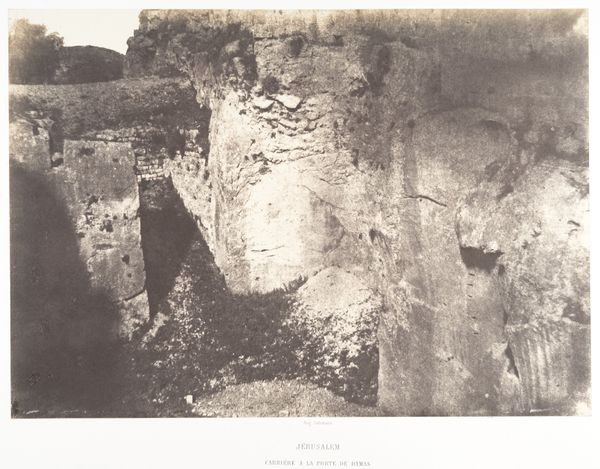

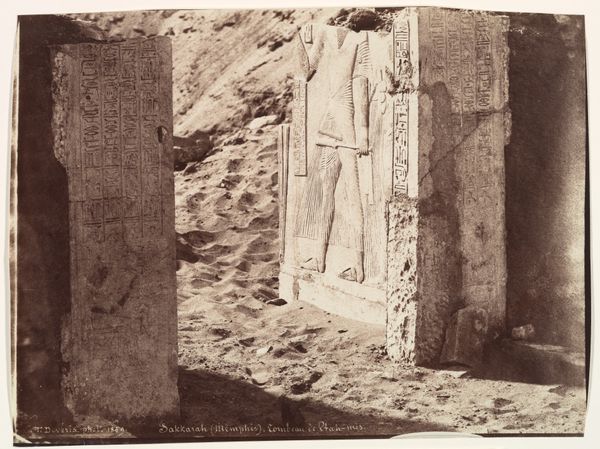

Editor: This photograph, "Ile de Fîleh (Philæ), Premier Pylône, Inscription Française Gravée Sur L'Ébrasement Oriental, En M" by Félix Teynard, was taken sometime between 1851 and 1852, using a gelatin silver print. The image features monumental architecture and what appears to be extensive relief carvings, all rendered in monochrome. The photograph’s subject matter really evokes a sense of antiquity. How do you interpret this work, given its historical context and photographic processes? Curator: For me, this piece speaks to the material and social aspects of image-making. Think about Teynard’s photographic expeditions: they required significant resources and labor. The journey to Egypt, the developing of the photographs, and the subsequent dissemination, all speak to the industrialized processes starting to take hold at this time. How does the presence of the French inscription complicate this, considering issues of colonialism and the consumption of culture? Editor: That’s an interesting point. I hadn’t considered the colonial undertones of the French inscription and the extraction of culture it seems to imply. So you're saying it highlights not just the art itself, but also the means by which it was obtained, circulated, and, in a way, consumed? Curator: Precisely. Consider the relationship between the photographer, the photographed, and the eventual consumer of the image. The gelatin silver print becomes a commodity, stripped from its original context, furthering an imperial narrative through photographic means. What labour went into extracting and transporting stone from its quarry to erect it to be recorded and repatriated for study? The means of making is just as vital to examine as what’s made. Editor: I see. So it really makes you think about who is doing the telling of this story. Thanks for pointing out the deeper layers of meaning within this photograph. I will never see it the same way. Curator: Exactly! It is key to understanding how an image can reflect material conditions of production, class, and power dynamics.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.