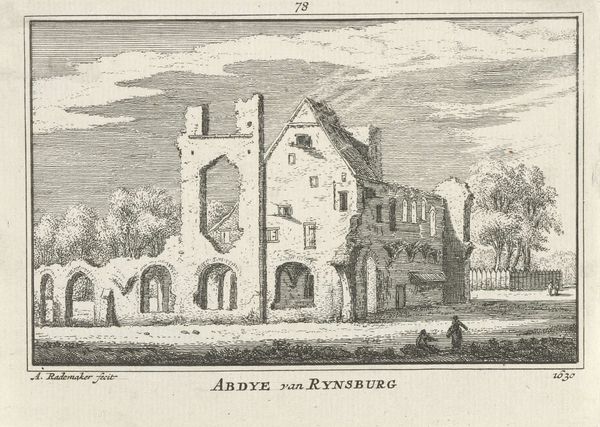

Gezicht op de abdij en de Buurkerk te Egmond-Binnen, 1680 1727 - 1733

0:00

0:00

abrahamrademaker

Rijksmuseum

print, engraving

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

# print

#

landscape

#

cityscape

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 80 mm, width 115 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Abraham Rademaker’s “View of the Abbey and the Buurkerk at Egmond-Binnen, 1680,” dating from 1727-1733, presents us with an engraving of a haunting scene. Editor: Haunting is definitely the word. The ruins of the abbey really dominate the print; they stand as a stark reminder of destruction and time's passage. You immediately note the textures, and the meticulousness of the engraving, even capturing the roughness of the broken stone. Curator: Rademaker made a career out of documenting places and buildings, a sort of topographical portraiture, if you will. The ruins, while physically crumbling, carry immense symbolic weight – perhaps reflecting the tumultuous religious and political landscape of the Netherlands at that time. We can draw parallels between these ruins and, say, the fractured social structures that characterized this early modern period. Editor: It makes me wonder about the engraving process itself, which certainly mirrors a broader labor division during the Dutch Golden Age, you know? Here's Rademaker meticulously transferring the physical reality, mediating it via skilled artisans—it raises questions about value, authorship, and the consumption of these images. Curator: Exactly! Think about how these images circulated. They weren't merely aesthetic objects; they were commodities that reinforced specific ideologies and class structures. Did the ruins represent something lost? Or, were they instead viewed as symbols of resilience, echoing the way Dutch identity was being constructed and reconstructed after periods of conflict? Editor: Well, maybe both? It’s interesting how the artist uses this elevated view, and the linear nature of engraving, almost mass-producing history, standardizing the visual consumption of Dutch heritage in ways we might link with contemporary mass tourism and production. Curator: This image speaks to layers of Dutch history – war, religion, economic development – and its place within art history is no less layered. The landscape is infused with these meanings, becoming almost a theater for the drama of national identity. Editor: Indeed, it gives us a lot to think about how material realities like engravings helped form abstract concepts of heritage and history, not to mention that buildings aren't eternal, everything degrades under specific materials and making conditions. It's something contemporary artists might play with today. Curator: Ultimately, reflecting on these visual echoes from centuries ago allows us to reexamine and reinterpret, questioning everything including the ways art interacts with the political and social contexts that mold it.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.