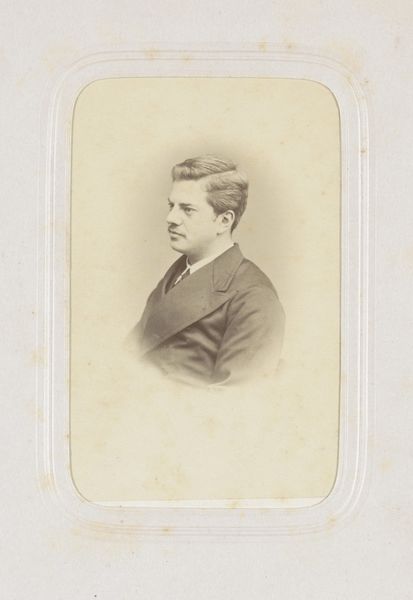

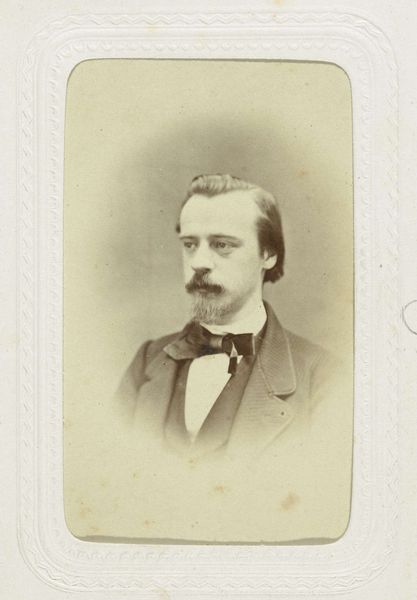

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

portrait

#

16_19th-century

#

photography

#

historical photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

19th century

#

realism

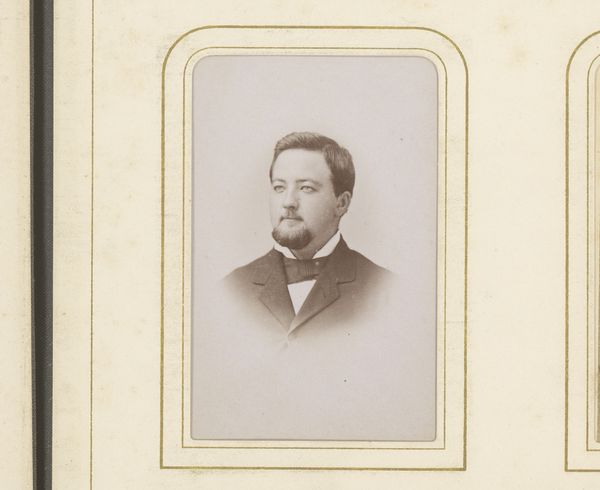

Dimensions: height 84 mm, width 51 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: A touch mournful, wouldn't you say? The way the light almost... swaddles him in a sepia melancholy. Editor: Yes, the effect is somber. This is listed as "Portret van een man," or "Portrait of a Man," an exquisite gelatin-silver print taken sometime between 1860 and 1880, presently housed in the Rijksmuseum collection. There's an inherent poignancy to these 19th-century portraits. Curator: Precisely! Photography was still finding its visual language then. The somberness, the posed stillness – these all contributed to the weight an image carried. It's interesting how the artist blurs the background, as though fading the material world in comparison with what lies in front of the camera. The framing seems to indicate its original context within an album page too, like one image among many other collected memories. Editor: That's a astute reading, yes. What I find fascinating is the leveling effect photography had—and continues to have—on class. Though only the burgeoning middle classes could readily afford photographic portraits at this time, their aspiration to gentry style—which he certainly adopts here, though conservatively—becomes accessible through this emerging technology. Look at the precise framing and the subject's meticulous composure—how powerful it was, I imagine, to capture oneself like this! Curator: Indeed. And perhaps there's a trace of that revolutionary potential visible here? In that confident—almost defiant—stare, a hint of a man claiming his own image, his own narrative in a world that might prefer he remain unseen. Note too how the light brings out so much more life on his face than is reflected from his starkly colorless suit and bow tie. Editor: A fascinating point. That said, photography in its earliest iterations very quickly served the burgeoning needs of the nation state. Think of ethnographic catalogs used in service of colonialism, for example. This more private context provides a gentler glimpse into how these tools become instruments of social aspirations. Curator: And that's why this piece holds my attention—it allows so much space for personal interpretation despite its rather simple composition. Editor: Absolutely. It reminds us that even seemingly straightforward images are entangled with complex histories and human aspirations.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.