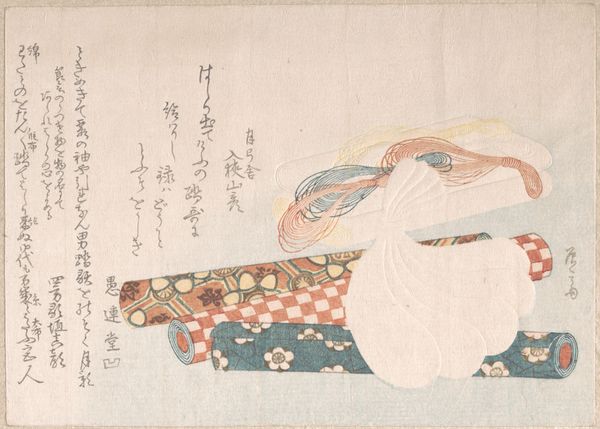

Hama-yumi and Buriburi-gitcho; Both Ceremonial Toys of Boys for the New Year 19th century

0:00

0:00

print, woodblock-print

# print

#

asian-art

#

ukiyo-e

#

woodblock-print

Dimensions: 5 1/2 x 7 7/16 in. (14 x 18.9 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

Curator: I am struck by the delicate, almost ephemeral quality of this 19th-century woodblock print. Ryūryūkyo Shinsai's "Hama-yumi and Buriburi-gitcho; Both Ceremonial Toys of Boys for the New Year" is, at first glance, deceptively simple. Editor: I agree, initially unassuming. Yet there’s an immediate sense of festive calm, the gentle tones hinting at quiet winter celebrations. A world away from today's consumerist frenzy during the holidays. Curator: Absolutely. Consider the techniques inherent in its crafting; each line, each block of color requires carving and precision, demonstrating skill that elevates the commonplace, children's toys no less, into high art, destined for bourgeois domestic settings. Editor: And speaking of those toys, observe the powerful cultural messaging within them. The hama-yumi, or demon-breaking bow, and buriburi-gitcho, a kind of spinning toy, are not mere playthings. They embody aspirations for protection, health, and good fortune, laden with symbolic weight and reflecting desires for a prosperous year to come. Curator: And this reveals interesting connections: we see production that requires skilled hands, an artistic process involving labor and a desire that reflects popular Japanese culture, but with elite appreciation in mind. There is tension. Editor: Precisely, and these connections point toward ritual acts beyond childhood whimsy. New Year festivities involve cleansing and renewal, ridding the past year of bad luck while heralding good fortune. Here are toys that play symbolic roles in those rituals. They evoke folk practices designed to protect against illness and disaster. The craftsmanship adds reverence, transforming the ephemeral into something significant. Curator: What the composition reveals is an interesting point—look closely at Shinsai’s materials, though they have changed color and aged slightly over time, this does tell us the composition and type of paper employed for reproduction were intentionally chosen for their texture and the way they would pick up the ink. It speaks of thoughtful production and access to select resources. Editor: Considering its placement at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a global art institution, it also highlights its cross-cultural reach. Objects carrying such symbolic weight connect generations with visual cues for how families have imagined hope. Curator: Right. The making, after all, speaks of the movement of knowledge and expertise in artisan industries—laborious hours embedded in festive iconography, reflecting shifting perceptions of value over time. Editor: Ultimately, Shinsai's humble still-life quietly whispers of profound cultural narratives embedded in objects and how they bridge art, ritual, and memory.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.