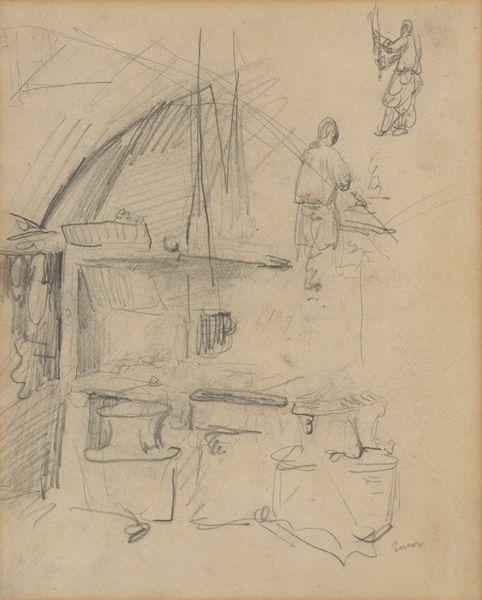

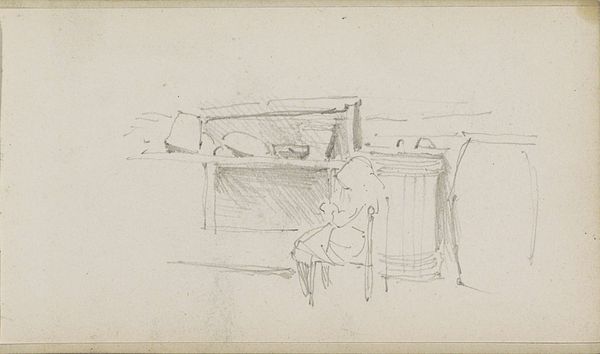

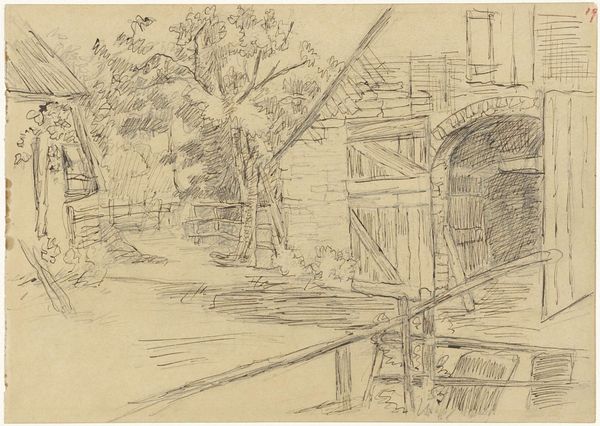

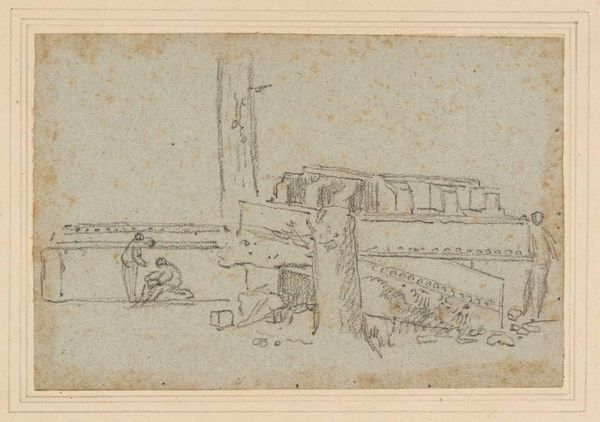

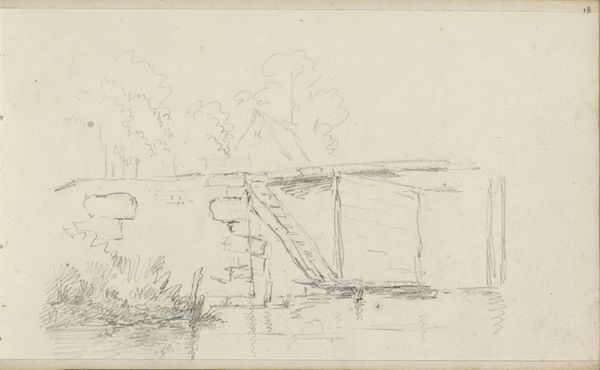

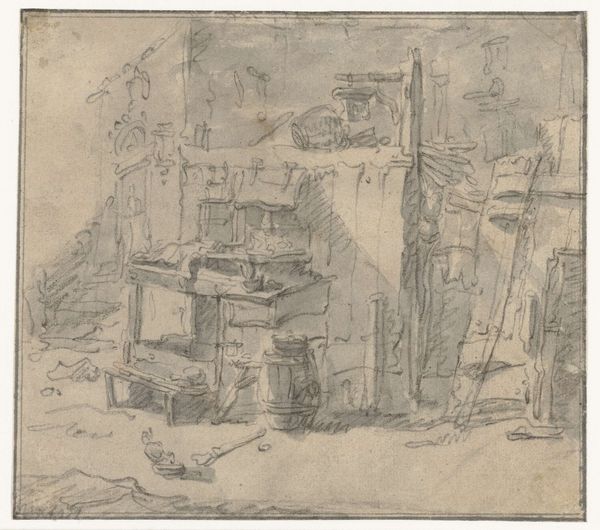

drawing, pencil

drawing

landscape

romanticism

pencil

Dimensions: height 79 mm, width 102 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is Georges Michel’s “Waterput,” a pencil drawing dated sometime between 1773 and 1843. It feels incredibly raw and immediate. I’m curious about how it fits within the artistic and cultural landscape of its time. What can you tell me about its historical context? Curator: It's fascinating how Michel captured this seemingly mundane scene, isn’t it? Consider the era: late 18th and early 19th century. What were the predominant artistic movements influencing artists at the time? Where and for whom might these sorts of images have been consumed? Editor: Well, I know Romanticism was big, valuing emotion and the power of nature. And it seems like those sorts of art were generally accessible through exhibitions and the art market that was developing then? This work's location, though, seems very humble for romanticism... Curator: Precisely! The accessibility is key. Romanticism often involved grand landscapes and dramatic historical scenes exhibited publicly to promote certain ideas. Now, think about this unassuming drawing. Its intimate scale suggests it might be intended for private contemplation. Does this drawing reinforce the established socio-political narrative, or perhaps present an alternative viewpoint through the common, workaday activity depicted? Editor: Hmmm, that perspective makes me wonder if he saw something beautiful and powerful in ordinary life, not just dramatic events. The focus is not some king or important battle; it’s a water well! Maybe a silent critique through visual language of what society and museums prioritized? Curator: An interesting counterpoint, certainly. This work can definitely be understood in relationship with the rise of "the common man" ideal spurred during this period of French social upheaval. What message about its historical period do you feel that the image can provide to today's viewers of Michel's work? Editor: I hadn't considered it that way before. Thank you! I think what really stands out for me now is seeing art not as just reflecting but as actively shaping the way we understand history and values. Curator: And hopefully, you will keep these kinds of questions in mind when assessing how socio-political power relates to image making going forward.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.