Copyright: Public domain

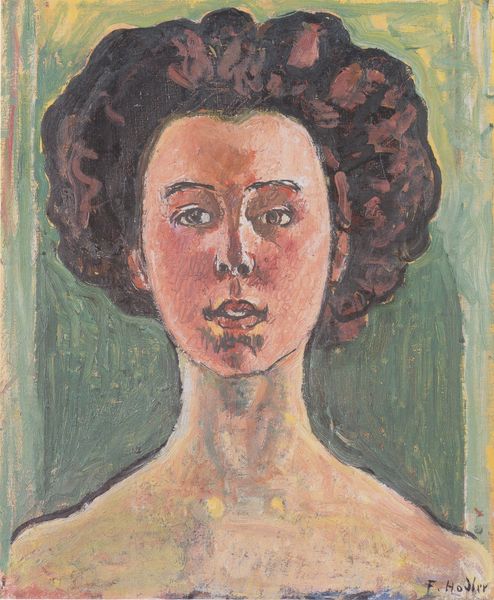

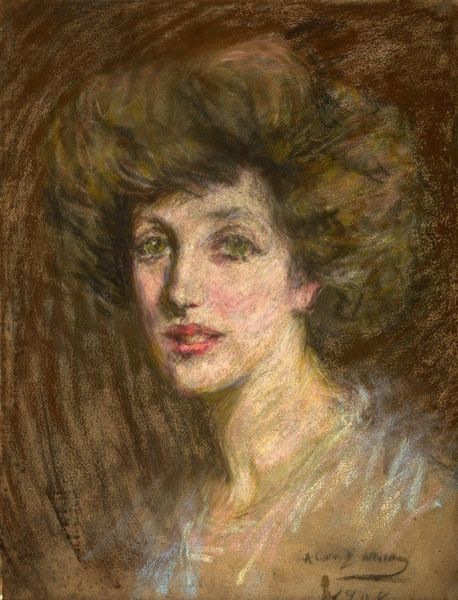

Editor: Here we have Ferdinand Hodler’s “Portrait of Giulia Leonardi,” painted around 1910. What strikes me most is the visible texture of the paint; you can really see the individual brushstrokes, even the way he's layered colors on her face. How do you approach this work? Curator: It's important to consider the context of its production. Hodler, associated with symbolism and art nouveau, used industrial produced paints but defied the growing dominance of the art market. Notice the impasto technique, the thick application of oil paint. It's not merely decorative. Editor: It does make the painting feel very… tactile. But how does the materiality connect to Hodler's other concerns? Curator: Think about the burgeoning industries and consumerism of the time. Hodler's thick paint is a conscious assertion of the hand, a refusal to erase the labor involved. It becomes a statement against mass production, embedding a history of the artist’s process into the work itself. Also, what does this mean about labor? Was he alone in the studio, or were there assistants who also participated? Editor: So the physical qualities of the painting become a kind of record of the artistic process and resistance against industrialization? Curator: Exactly. The very 'stuff' of the portrait conveys a powerful social commentary, critiquing emerging consumption trends. Hodler doesn't just depict Giulia, he presents a crafted object imbued with values. Editor: That’s really shifted how I see this painting. I was focused on the face, but now I realize that the materials tell a deeper story. Thank you for illuminating these points. Curator: Absolutely. Always remember, what things are *made* of, is key.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.