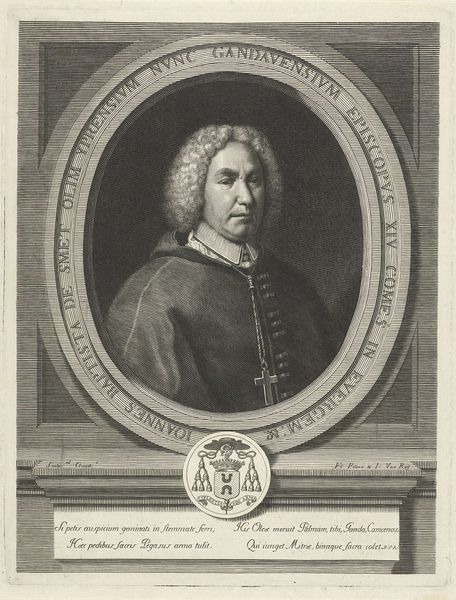

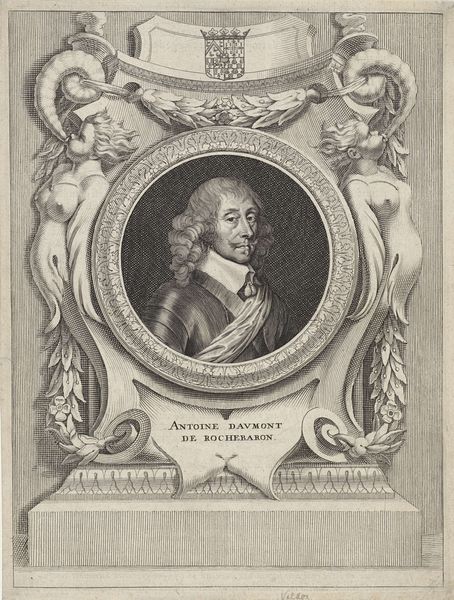

engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

#

academic-art

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 449 mm, width 364 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at this stately engraving, "Portrait of Claude de Saint-Georges" by Gérard Edelinck, circa 1652 to 1707 and held at the Rijksmuseum, the first thing that strikes me is the subject’s weighty presence. The texture achieved through engraving is fascinating – particularly the rendering of fabric and flesh. Editor: Indeed, there’s a tangible gravitas. And let’s not forget the political landscape, this is a portrait of an Archbishop, during a period marked by enormous social upheaval and religious reformation. The symbols, the clothing, even the stern look on his face, they all reinforce his authority, yet hint at a subtle underlying anxiety. Curator: The materiality of printmaking in itself offers so much – consider the deliberate choices in line and density, which elevate the Archbishop, giving form to the vestments. Think too about the means of distributing his image across the French Kingdom; the social implications for who could view, and then, by proxy, acquire it. Editor: Precisely, and considering the print's reproducibility is a key factor. This artwork provides a window into questions about power dynamics and religious structures during that epoch. The print suggests the image was created and used as a tool for upholding the existing hierarchical structure, for propaganda. Saint-George appears stoic, determined. But is that simply because of the conventions of Baroque portraiture? Or might he be feeling the squeeze, sensing an alteration to that historical hierarchy? Curator: An important thought. Consider too the role of the engraver, Edelinck; his studio, the economic factors dictating material costs, workshop apprentices, how prints moved across borders… each aspect influences meaning, even feeds into questions of authorship. Did the commission stipulate the symbols? What did Saint-Georges think? Editor: And what message does this broadcast about French national identity and spiritual authority? To the largely illiterate masses, such icons were often a form of religious education, or political endorsement of aristocratic figures. Saint-Georges projects power, his regalia reinforces class divides, his very image serving as a reminder of strictures against deviation. Curator: True. Examining these production practices reveals fascinating tensions between craft, high art and wider social status. This piece also challenges our notions of artistic value: How should we price the labour of printing and reproductive artworks like this portrait? Editor: Ultimately, these dual layers - of process and societal weight, intersect, challenging the ways art can reflect and reinforce power. Considering Edelinck and Saint-Georges in light of historical dynamics highlights both creative innovation and social pressures embedded within this Baroque image. Curator: Exactly, considering how printmakers shape the perceptions of powerful leaders through material form reminds us of artistry that's always involved and responsive to culture, even centuries on. Editor: Indeed. Thinking critically about these intersectional narratives enriches how we engage with works like this, adding depth to how they communicate power.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.