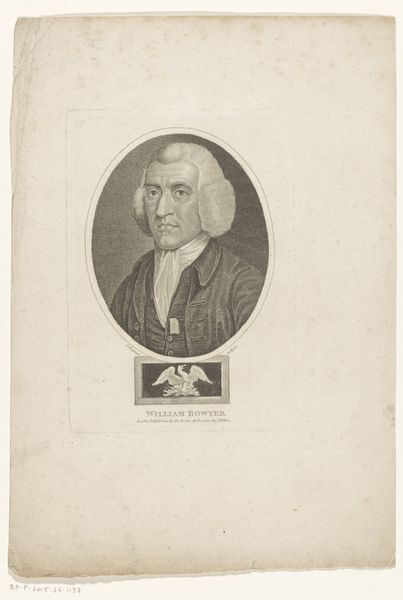

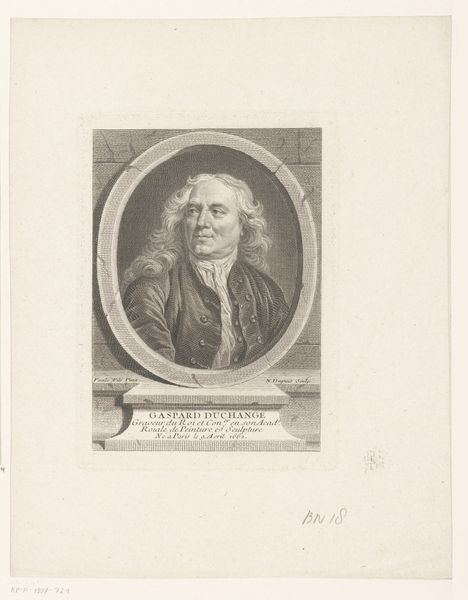

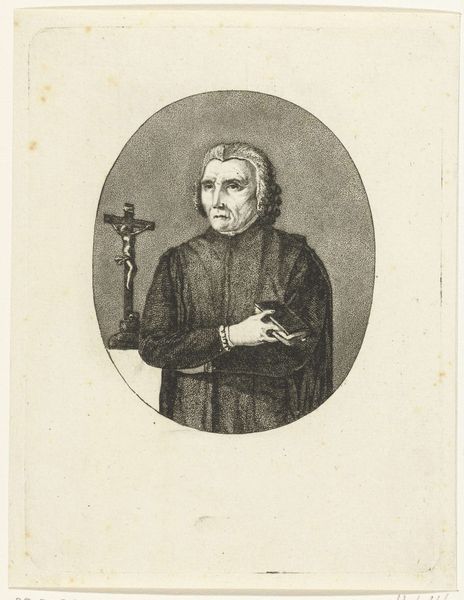

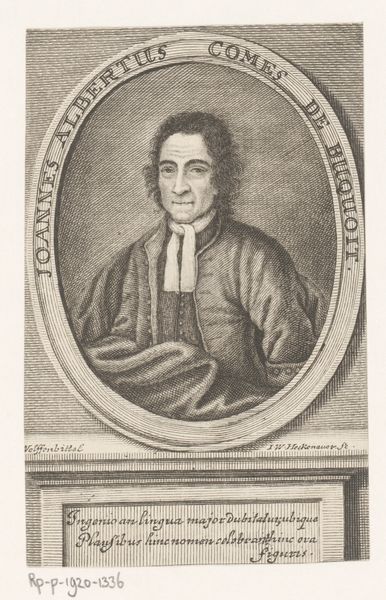

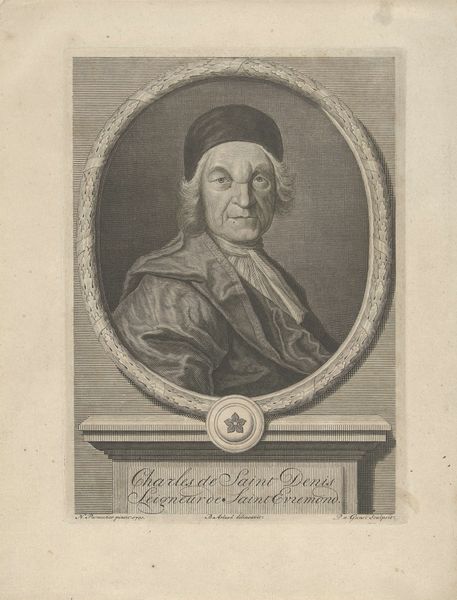

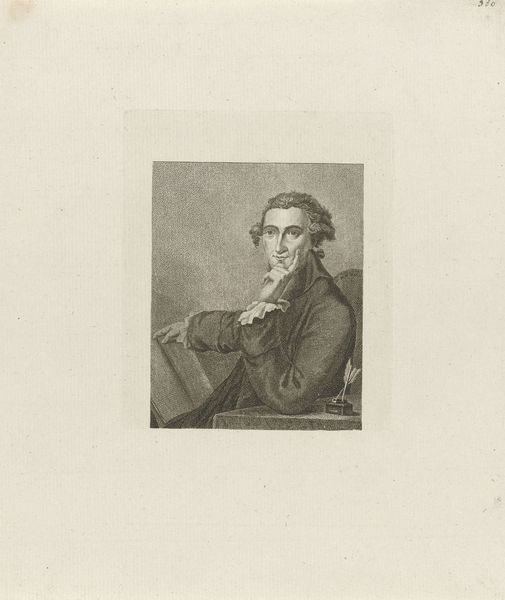

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

neoclacissism

# print

#

old engraving style

#

19th century

#

portrait drawing

#

history-painting

#

engraving

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

Curator: This print is titled "Leonard Euler," likely created around 1804. It's attributed to John Chapman, executed in the Neoclassical style as an engraving. I always find these historical prints so compelling. Editor: My immediate thought is how meticulously crafted this portrait is! You can practically feel the texture of the paper it's printed on. The hatching and cross-hatching gives such incredible detail. Curator: Absolutely. And what I find so captivating is the implied narrative within. Euler is, of course, prominently featured, but underneath there's a smaller scene: Euler dictating mathematical equations. I wonder about the process by which images of scientific labor were disseminated. Editor: Ah, that gets to the heart of it, doesn't it? We often think of art in terms of solitary genius, but this print shows how collaborative knowledge production really is, dependent upon various kinds of labor. Look at the line quality achieved through engraving, then reproduction and distribution through print media. The small image suggests the conditions in which scientific breakthroughs take place! It adds layers of value by making that work visible. Curator: Exactly. It is also evocative of that historical moment. The fur collar, for example, provides an excellent point of entry into the past and reminds us of material comforts during the period of Neoclassicism. There's also the matter of social mobility reflected in how Euler came to be a prominent figure. Editor: Right, you see both intellectual prestige and access to production intersecting here. Think about the communities that would form around prints like this, and the intellectual and material investment that created networks across the sciences and arts. How do we account for that social life? Curator: A crucial question, indeed. What’s especially revealing is the artist's aim to present science through a classical lens. There’s an interesting paradox here, reflecting perhaps how novel Enlightenment sciences are nonetheless framed. Editor: Well said. It demonstrates a shift where new sciences, supported by new kinds of production, were presented to the masses in familiar modes of representation. The act of studying or understanding in Euler's time might seem quite remote to contemporary observers. Curator: True, seeing the intersections, as we have, encourages a greater sense of nuance. Editor: Yes. Thank you for pointing out how this particular work bridges between social labor, high intellectualism and novel techniques for visual circulation.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.