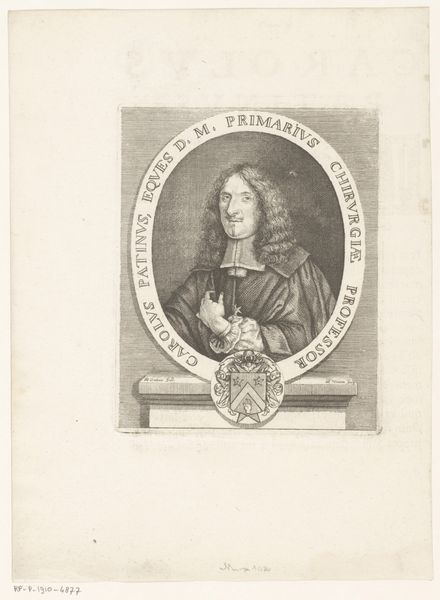

print, engraving

#

portrait

#

baroque

# print

#

engraving

Dimensions: height 150 mm, width 105 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

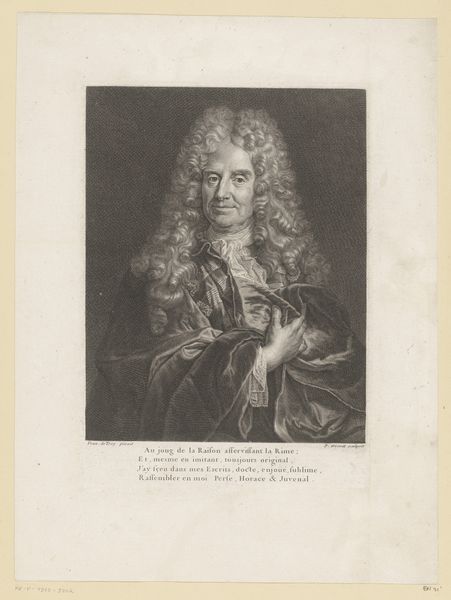

Curator: Looking at this print, "Portret van Charles Patin," made between 1704 and 1765 by Johann Friedrich Schmidt, a striking formality immediately comes to mind. The gentleman exudes wealth, authority, and...dare I say... perhaps a touch of boredom? Editor: It’s the hands, I think. They’re so meticulously rendered in the engraving; you can practically feel the texture of the gloves, but their stillness also implies a certain leisure class. What were the socio-political factors influencing the subject matter chosen by printmakers at that time? Was there a thriving market for disseminating images of notables like Charles Patin? Curator: Absolutely. Schmidt capitalized on the expanding print market. Engravings like these served not only as portraits, but also as assertions of social standing, consumed by those aspiring to the depicted lifestyle or connected with learned circles like the one Patin belonged to. Notice the subtle gradation of tone achieved by Schmidt in rendering the details of the sitter’s voluminous wig. The quality of line speaks volumes about the skill and labor required to create the matrix and print edition. Editor: The lines really define everything. The cross-hatching gives depth to the velvet robe. But it's important to understand the cultural impact this type of portraiture had on shaping public perception. We’re not simply observing an individual; we're witnessing a constructed image meant for widespread distribution and consumption, influencing and reinforcing societal norms about status. How was someone like Schmidt compensated for his labor? Was it piecework, or was he subsidized by powerful patrons? Curator: Research suggests it was often a combination, perhaps driven by commissions but with scope for commercial sale beyond, granting Schmidt economic freedom and creative license in presenting his subject for broader social appreciation. These prints weren't disposable; they represented investments in material culture. The ink, the paper—even the act of collecting testified to the owner’s social awareness and aspirations. Editor: So, more than just depicting Charles Patin, this portrait performs social work. And understanding the context of its creation and dissemination highlights the politics embedded in early modern imagery. Curator: Precisely. And it’s a perspective that deepens our appreciation for the artwork beyond its aesthetic qualities. Editor: Indeed. Analyzing art from these viewpoints allows a much richer exploration of not only the artist, but the sitter and its impact to viewers near three centuries ago.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.