#

portrait

#

baroque

#

oil painting

#

history-painting

#

watercolor

Dimensions: height 218 mm, width 161 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

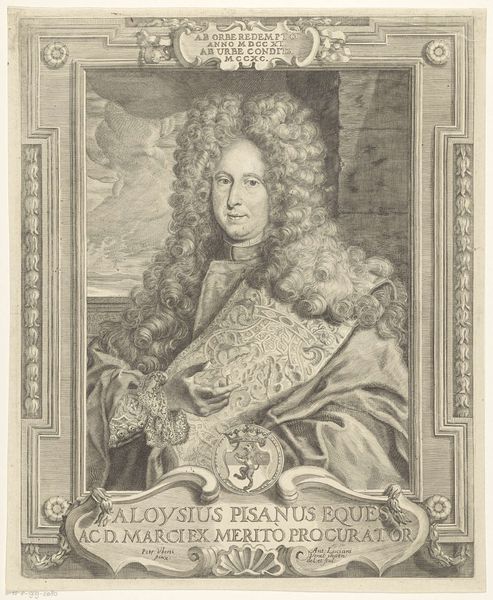

Curator: Before us, we have "Portret van Romeyn de Hooghe," created sometime between 1730 and 1750. The piece is held here at the Rijksmuseum. Editor: It possesses such a captivating, dream-like quality. The soft watercolors create a beautiful luminous effect. The composition draws the eye directly to the sitter's face. Curator: The oval frame immediately imposes order, providing a visual hierarchy that spotlights de Hooghe and the carefully arranged heraldic details above, while anchoring the subject via the inscription. Editor: True, I note that the inscription describes him as a "pictor, incisor, autor et poeta." That’s quite the billing for a man who’s basically unknown today. Tell me about Romeyn de Hooghe’s historical context. Who was this man and why did the museum choose to spotlight him now? Curator: Romeyn de Hooghe was an important late Dutch Golden Age etcher, caricaturist, and political propagandist. A multi-faceted talent. He had the unique perspective of bridging the 17th and 18th centuries as he became widely renowned for his detailed allegorical prints, chronicling the Dutch Republic and beyond. Editor: I wonder, how effective could caricature be, in such times? The political power must have greatly shifted after a piece like this went up. Curator: Caricature served to solidify the views held by the already converted—creating more fervor, which had long-lasting effects on both commerce and power relations of the Dutch Republic. However, this piece deviates somewhat from de Hooghe’s widely acknowledged satirical repertoire. Instead, this subdued rendering attempts to canonize him through emblems of personal virtues that were crucial at that historical juncture. Editor: That artistic choice feels decidedly like propaganda then; more of a public service than art at times. The use of iconography can never be divorced from the intentions of those funding or controlling it. Curator: Precisely, though such close readings sometimes can obscure an object's undeniable power and careful craftsmanship in imbuing Baroque aesthetics. I am particularly drawn to the tactile interplay of cherubic figures alongside what could otherwise be cold, heraldic emblems—resulting in such uniquely vibrant rendering in a period when the engraver began losing social capital within the Dutch republic. Editor: What I am more taken with is its accessibility. It’s remarkable how the personal story becomes the larger canvas on which culture, art, and political forces engage. It truly transforms one's understanding.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.