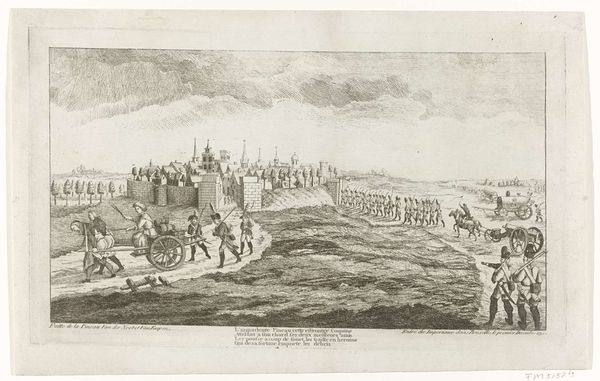

Dimensions: height 222 mm, width 322 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: So, this is "Processie van flagellanten," or "Procession of Flagellants," an engraving made by Caspar Jacobsz. Philips sometime between 1752 and 1789. The scene feels, I don’t know, a little unsettling given its repetitive figures. What do you see in this piece that stands out in terms of the visual language used? Curator: It is indeed a powerful, if disturbing, image. Notice how Philips uses the procession, snaking its way into the distance, not just as a depiction of an event, but as a potent symbol. Flagellation, the act of whipping oneself, carries heavy emotional and psychological baggage across cultures, signifying penance, purification, and even ecstatic religious experience. What feelings are evoked for you by the long winding line of these figures? Editor: It's bleak, I think? They seem almost dehumanized. A faceless mass… Were flagellants always viewed this way? Curator: Consider that public flagellation was a recurring phenomenon in Europe for centuries. Often connected to times of crisis, perhaps plague or famine. In these contexts, such public displays took on layers of meaning beyond simple penance. It’s catharsis. Community, in a time of isolation. Think about the ritualistic aspects – the repetitive motion, the physical suffering shared publicly. How does that shift your perspective on the symbolism here? Editor: So it's not *just* about the punishment? Curator: Not at all. It becomes about cultural memory. About shared trauma and seeking solace through collective, visible suffering. Think about how the artist uses the engraving medium itself – those fine lines creating the illusion of both detail and distance – to reinforce this idea of a collective, almost endless act. It really makes me think about the cyclical nature of history, and how these intense emotional displays keep resurfacing across generations. Editor: That’s a great point; viewing this image is a window to those recurring expressions of communal grief. Thank you. Curator: Indeed. Understanding these historical contexts, even just a little, enriches our engagement with this powerful, evocative print.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.