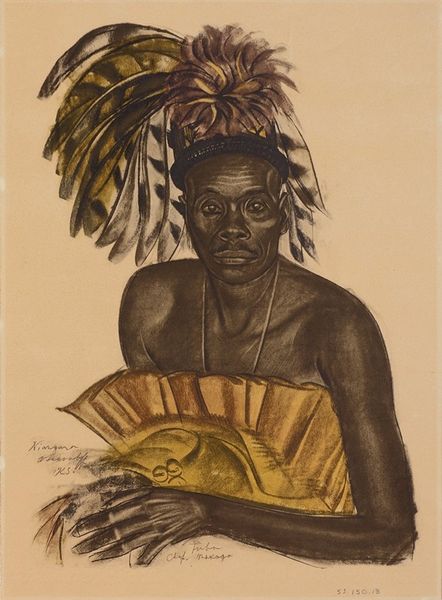

drawing, charcoal

#

portrait

#

pencil drawn

#

drawing

#

figurative

#

pencil sketch

#

charcoal drawing

#

figuration

#

pencil drawing

#

portrait drawing

#

charcoal

#

academic-art

Copyright: Public Domain: Artvee

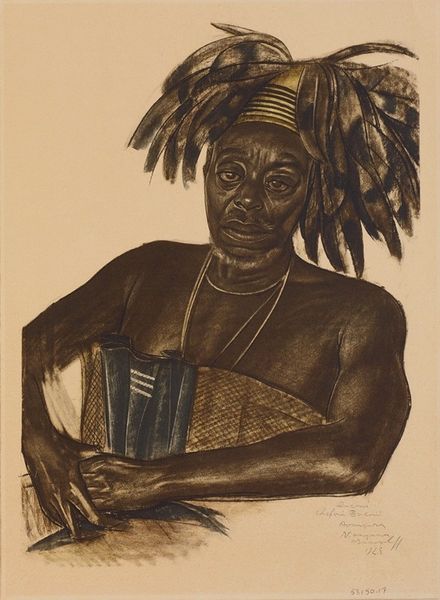

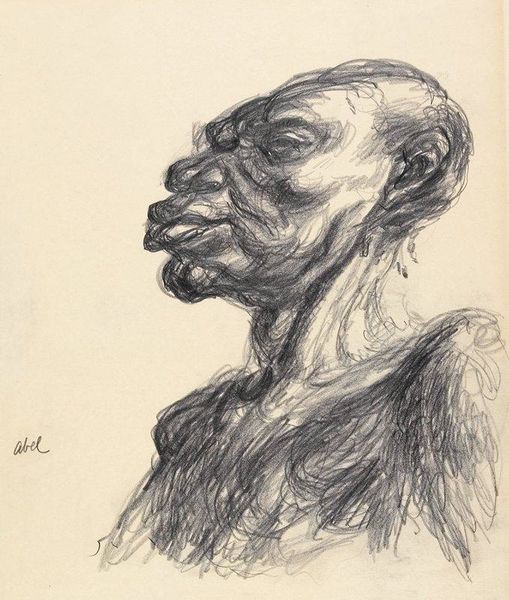

Curator: Standing before us is "Aboura," a charcoal and pencil drawing created in 1925 by Alexandre Jacovleff. It's a powerful portrait that captures the sitter's gaze, and it seems so very intent. Editor: It's hauntingly beautiful. The charcoal gives it a ghostly quality, almost as if the figure is emerging from another dimension. What's with the magnificent headpiece, some sort of halo of feathers, very commanding, in fact? Curator: It appears to be an elaborate headdress, a likely marker of status and cultural identity. Considering Jacovleff's background and travels, it invites questions about representation, power dynamics, and the gaze inherent in portraiture within a colonial context. I understand that "Aboura, chief de Banlieu Windsor (Ouagadougou)" is inscribed in pencil near the figure. Editor: Oh, that puts a completely different spin on it. It's no longer just an image but a document, a record of a meeting between artist and subject. A leader in all his regalia... It seems almost urgent somehow. Is it meant to document an event? A negotiation of some sort? Curator: Indeed, it becomes critical to acknowledge the social, economic, and historical realities framing this encounter. Who was Aboura? What was the context of his chieftaincy? Jacovleff’s artistic project needs to be seen against broader colonial narratives, class divides, and ethnographic studies of that time. Editor: I'm still stuck on those feathers. They add such dramatic flair. It's like, is he adorned or burdened? The lines of the drawing create such movement...almost as if the air vibrates around him, creating this halo effect and a unique story between them. Curator: Those questions regarding adornment versus burden and your immediate, almost visceral reaction, offer critical entry points for a deeper analysis of how cultural symbols are deployed, understood, and sometimes misinterpreted. Editor: It gives a face and being to people and, by proxy, gives respect in some way. I find I respect and value both, with just one look, and then ask myself a million questions afterward! What a thing of beauty! Curator: And isn’t it precisely in that dynamic—in the initial visceral encounter prompting subsequent critical inquiry—that the power of art resides? It is, when properly activated and approached, a space for meaningful intersectional discourse.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.