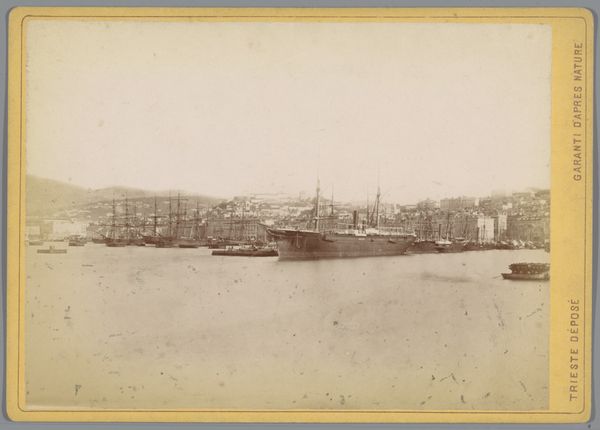

photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

landscape

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

cityscape

#

genre-painting

#

realism

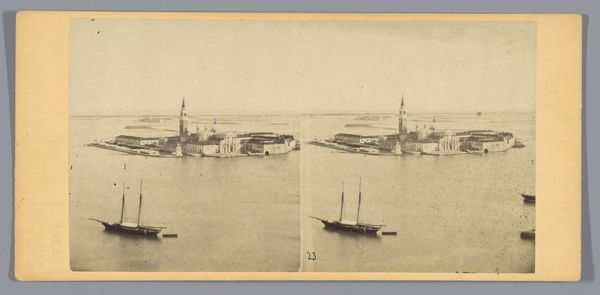

Dimensions: height 169 mm, width 224 mm, height 314 mm, width 450 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: This gelatin-silver print by Paul Güssfeldt, titled “The ship de Hohenzollern surrounded by full rowboats in a harbor,” captures a vibrant scene from 1889. It really evokes a strong sense of place, doesn’t it? Editor: Absolutely, but it also feels a bit melancholic. The sepia tone lends an air of faded grandeur, almost like a memory. And look at all those rowboats—packed with people yet they seem so quiet, reserved even. Curator: Perhaps the solemnity stems from what the ship, the Hohenzollern, would have represented: power, progress, perhaps even empire. Rowing towards such a vessel may have had symbolic significance for these citizens. The horizon, punctuated by that church spire, seems to balance temporal and spiritual authority, doesn’t it? Editor: True, but let’s not overlook the labor involved in creating this image. Consider the collodion process used at the time, the careful development needed to achieve this tonality on the gelatin-silver print. It is not only the event it pictures but also the photographic technique itself. Curator: Precisely. This choice of medium amplifies a tangible sense of history. Consider how, beyond simply documenting the day, Güssfeldt made active choices about composition that enhance deeper thematic concepts. It speaks volumes about this era's cultural memory. Editor: And about social structure. There's something quite telling in the mass production implied by all those nearly identical rowboats, all made in a shipyard or factory according to certain specifications of the day, but rowed with such human force, even skill. One questions what the meaning of each single one is! Curator: You've got me thinking… beyond the visible activity and historical event being pictured, the photograph creates the silent story of this society as a cohesive group working with similar purposes for all involved people to coexist in that era of Germany! The iconographical message it passes is astonishing. Editor: It’s about how our view shifts once we look at who labored. Knowing this image wasn't simply a snapshot changes the feeling drastically! It shifts it to a labor production site, it is a window to those who have never sailed! Curator: Yes, understanding the image through your materialist lens and mine, we see it is less a static snapshot, and more a meditation on labor, technology and national identity at a specific turning point in time. Editor: A point that shows the value of seeing through production and context to appreciate.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.