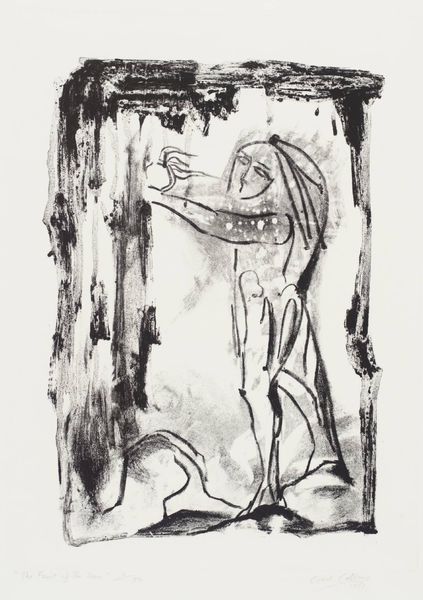

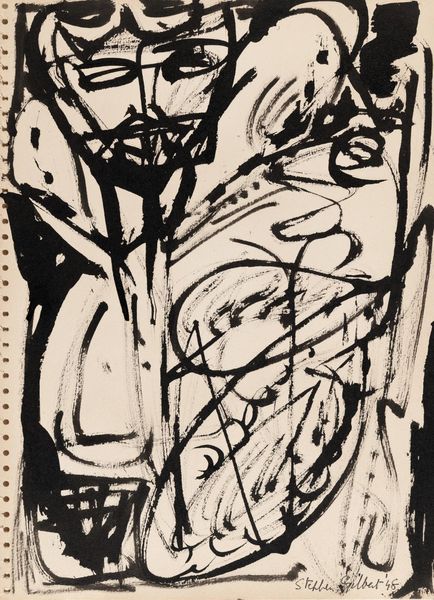

Dimensions: image: 405 x 305 mm

Copyright: © Tate | CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED, Photo: Tate

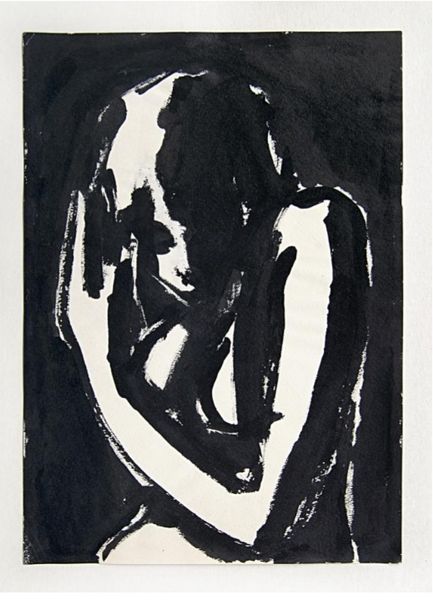

Curator: Cecil Collins' "Sybil," residing here at the Tate, presents a figure rendered in stark, bold strokes. It feels almost like a fragment. Editor: Indeed. The immediacy of the ink suggests a fleeting, almost ephemeral quality. A study in pure form, wouldn't you say? The figure barely coalesces. Curator: And yet, the title immediately invites broader cultural associations, hinting at classical mythology and the role of the prophetess in society. Consider how Collins uses these gestural marks to convey profound meaning. Editor: Precisely. It's the tension between the abstract and the figurative. He is probing the archetype with the least possible detail. The splash of ink near the lower left feels deliberate. A counterpoint? Curator: Perhaps. It could be a visual representation of the chaos inherent in prophecy itself. It’s a bold choice to leave it untitled. Editor: Yes, I believe we both came away with a deeper appreciation for the work, examining both its form and its historical implications.

Comments

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.

tate 10 months ago

⋮

Sybils, the women prophets of Greek and Roman legend, frequently appeared in Collins’s paintings and prints. He recounted in an interview in 1979: ‘They [Sybils] seem to be visions of certain functions of the feminine soul – prophetic, oracular, sometimes coming out of caves, guardians of altars, uttering prophesies. They are, as it were, the voice of the unknown or entries into the unknown land, guarded in my paintings, I think seldom by a man but practically always, by a woman or an Angel’ (Cecil Collins, ‘Theatre of the Soul’, interviews, 27 September and 13 October 1979, Keeble, p.121).