drawing, print, ink

#

portrait

#

drawing

# print

#

ink

#

men

Dimensions: Sheet: 18 1/4 × 14 5/16 in. (46.4 × 36.4 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

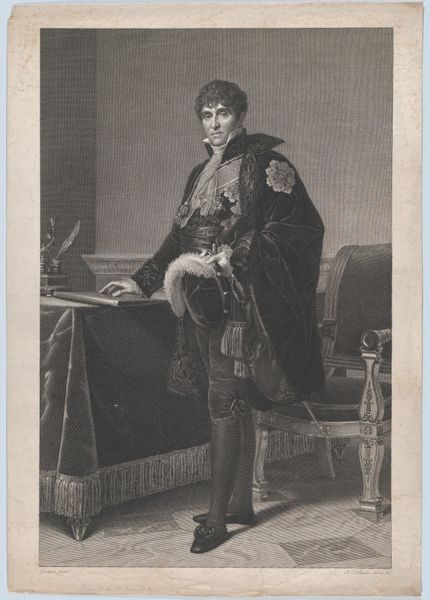

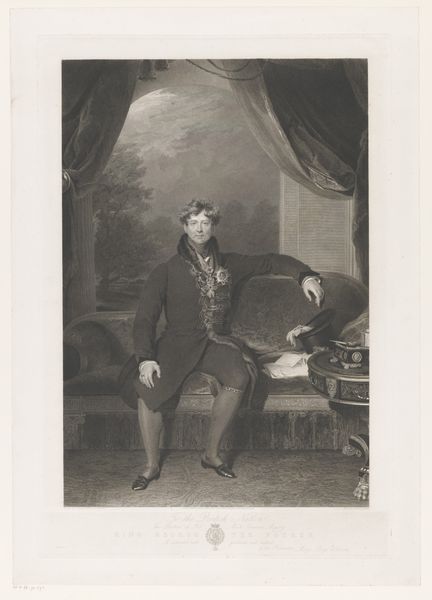

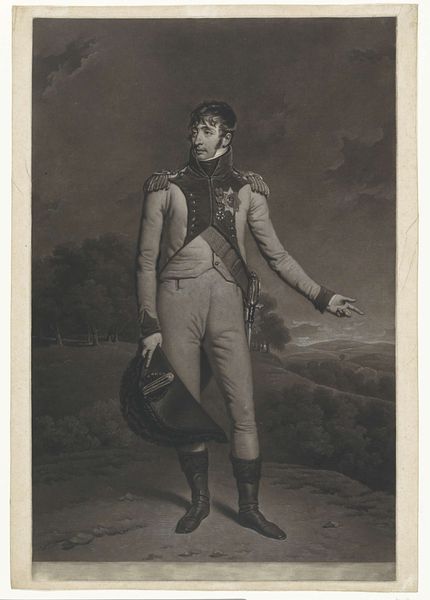

Curator: Before us we have "The Duke of Wellington," a print rendered in ink by William Say in 1828. Editor: My initial reaction is of stiff formality, wouldn’t you agree? It’s all hard lines and meticulously rendered finery. The man himself seems rather contained, even with the raised glass. Curator: I see the formality but also a distinct visual language of power. The raised glass, an age-old symbol of celebration, points to the Duke’s victories, solidified by the rich textures that emphasize his rank and prestige within the established order. His decorated clothing is quite fascinating. Editor: Indeed, all that finery acts as a visual declaration of dominance and privilege, no? The strategic composition underscores this—notice how the landscape in the background, viewed from above, mirrors his literal position of power. He figuratively surveys his domain. I feel like the portrait uses semiotics as a reinforcement of his authority in British history, a position often maintained through colonial violence and political maneuvering. Curator: Yes, and that background—suggesting London, perhaps—is bathed in a soft light that contrasts the foreground's sharp details. This light almost sanctifies the Duke and reinforces a sort of “divine right” visually linking his personal achievements to national ideals. This creates continuity to British identity. Editor: Yet, the continuity often overlooks the dissent, and, for those actively marginalized. Those national ideals weren't necessarily benevolent to all under British rule, or within Britain itself, right? Curator: That's a fair point. And it leads to how we should view Wellington. A man, or as an archetype for this time in history. As viewers, we must remember the visual narrative this image is creating. Editor: A constructed narrative, yes. Recognizing these elements and questioning them helps us critically engage with history rather than passively accept a triumphant, singular version of events. It pushes for broader understanding of society and historical influence. Curator: Absolutely. The interplay of iconographic cues encourages that deeper inquiry. Editor: So much for a simple toast, eh? It holds worlds within.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.