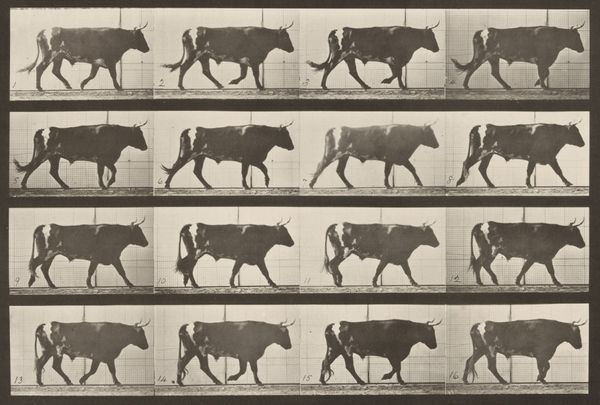

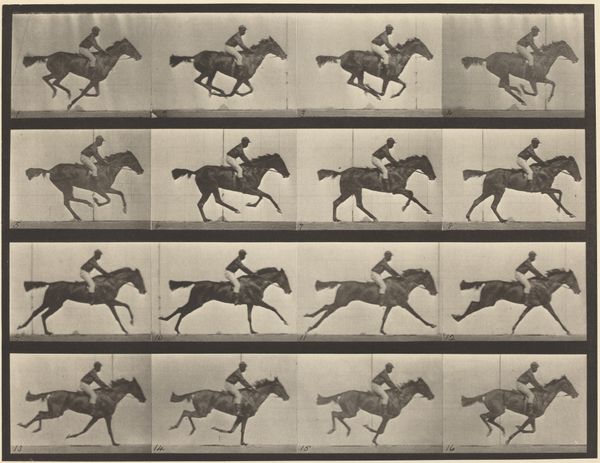

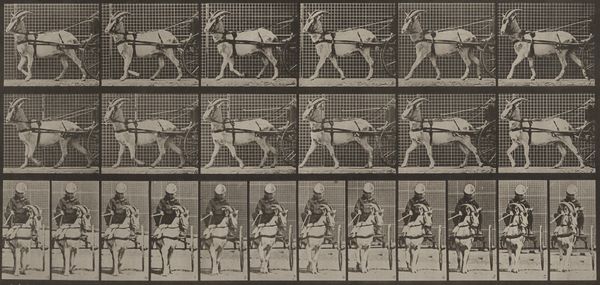

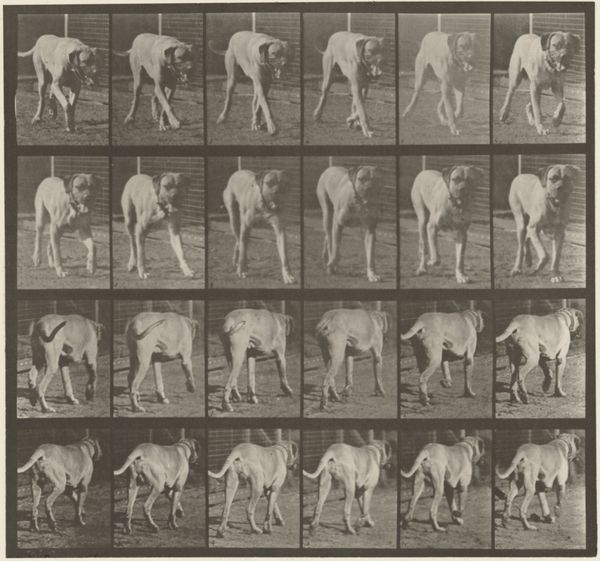

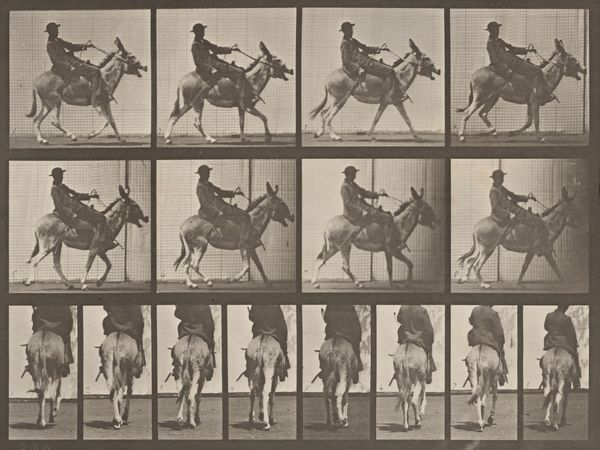

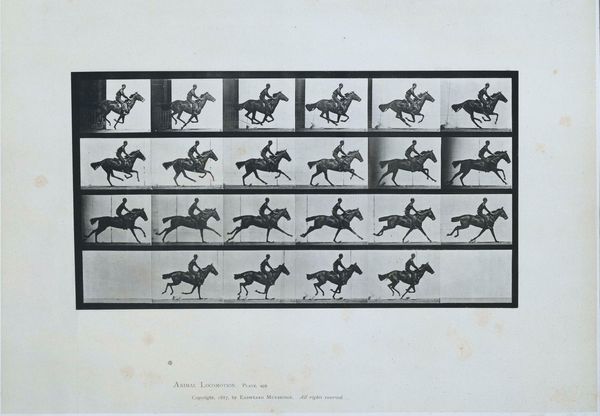

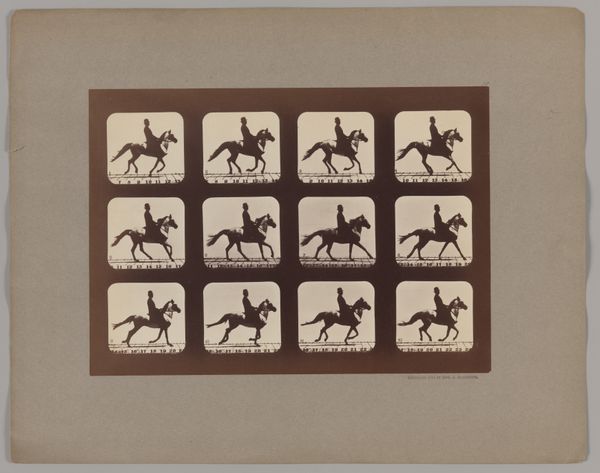

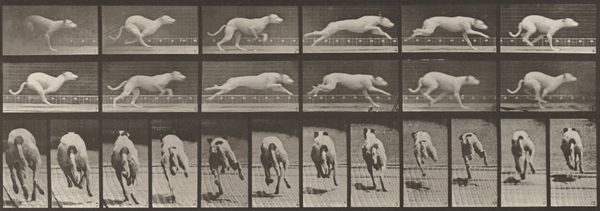

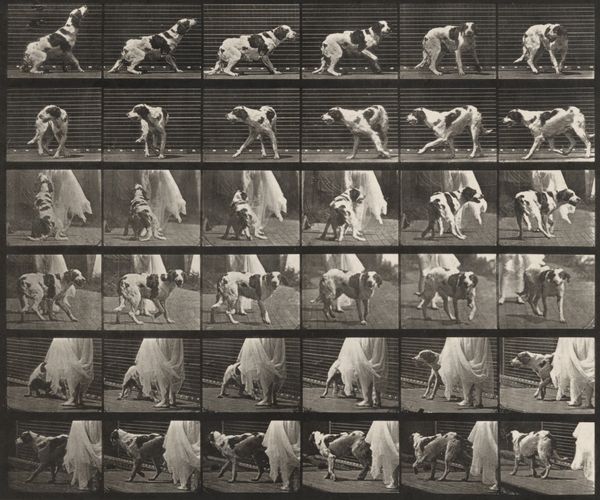

print, photography, gelatin-silver-print

#

animal

# print

#

photography

#

gelatin-silver-print

#

realism

Dimensions: image: 19.3 × 39 cm (7 5/8 × 15 3/8 in.) sheet: 46.1 × 60.4 cm (18 1/8 × 23 3/4 in.)

Copyright: National Gallery of Art: CC0 1.0

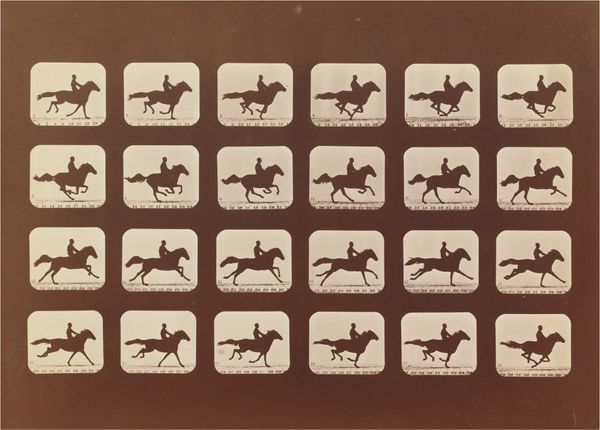

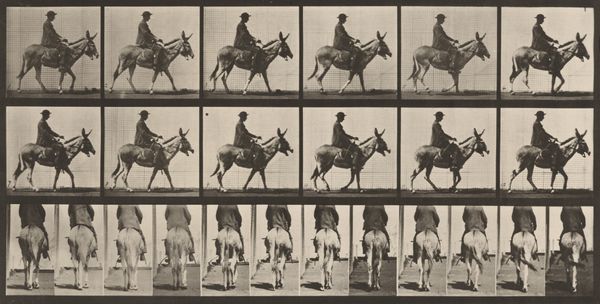

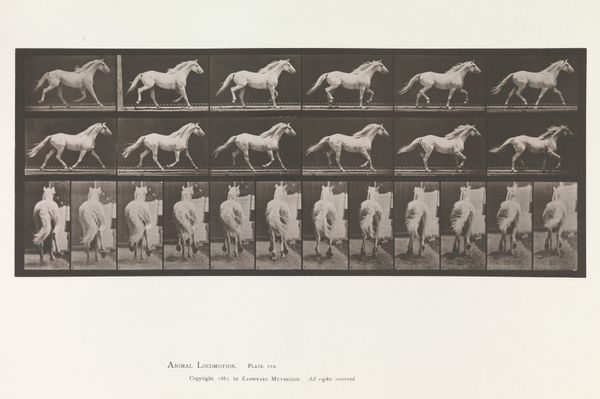

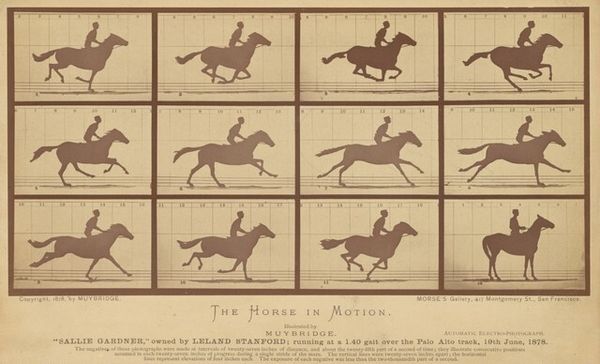

Curator: Right now we’re looking at "Plate Number 679. Goat; galloping," a gelatin silver print from 1887 by Eadweard Muybridge. Editor: My first thought? How scientific it looks. All those frames, that grid… it's like a lab experiment. Curator: Precisely! Muybridge was instrumental in bringing science into the realm of art. This series of photographs was intended to study animal locomotion, initially funded by Leland Stanford. Stanford had a theory that horses, during a gallop, lifted all four hooves off the ground simultaneously. Muybridge aimed to prove it. Editor: So, less about artistry and more about deconstructing movement into these discrete, almost manufactured steps? It feels like a commentary on labor, or perhaps the industrial dissection of nature itself. Each captured frame representing time, labor, resources put in by the artist for these prints, which were further studied, analyzed and published. Curator: The serial imagery was incredibly groundbreaking at the time. Not only did it resolve a debate in the art world of accurately representing movement, but it also became a pre-cursor to the technology of motion pictures and significantly changed visual culture and perception, challenging traditional boundaries in academic science and popular culture. Muybridge toured widely with the images, lecturing about the science of movement, making these photographic innovations available to all kinds of audiences. Editor: So its wide distribution contributed to its cultural influence? It’s fascinating how something meant to be purely observational took on so many layers. The image raises more questions than it answers: what exactly were the conditions of making these photographs? It all boils down to what gets captured, reproduced, and ultimately consumed in a rapidly changing technological environment. Curator: Absolutely. Muybridge blurred lines of high and low art, capturing something inherently beautiful—animal motion—and making it available for scientific and public scrutiny through mass-producible photographic methods. His legacy sits firmly in both art history and the history of science and technology, influencing many fields by shaping new avenues of artistic and scholarly explorations of modern life and visual perception. Editor: So in the end, it's more about motion and capturing the goat itself. More about how the photograph came to be and why? Fascinating. Curator: Exactly. A merging of science and art that reshaped both worlds.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.