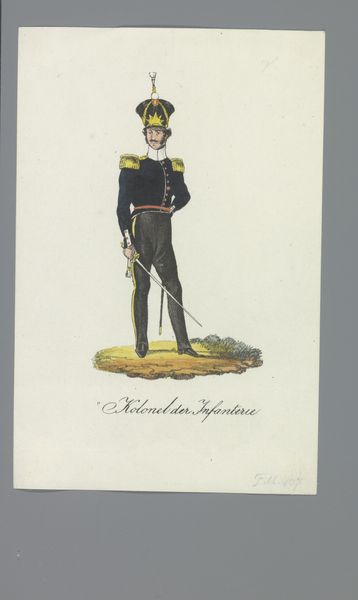

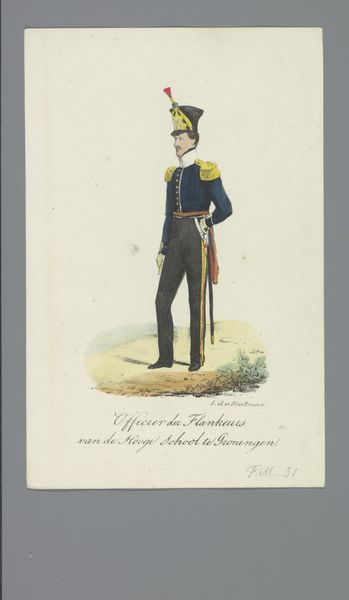

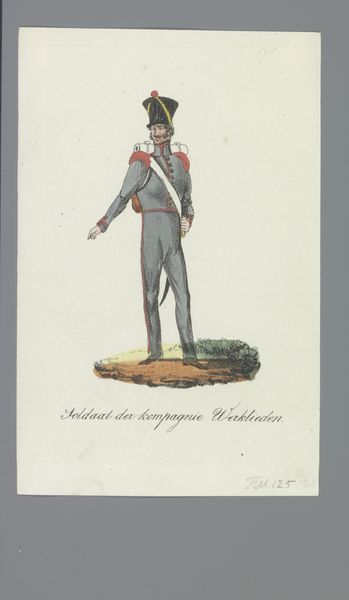

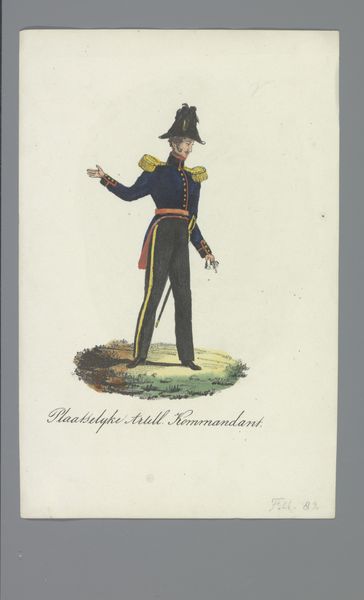

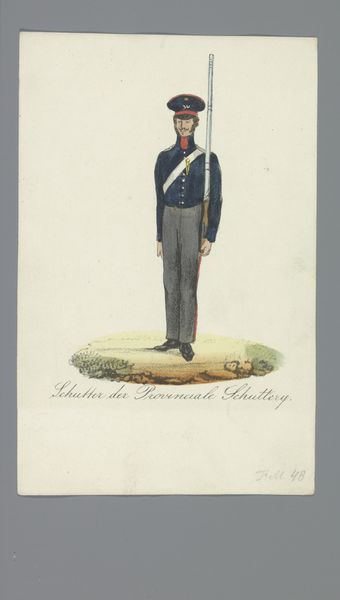

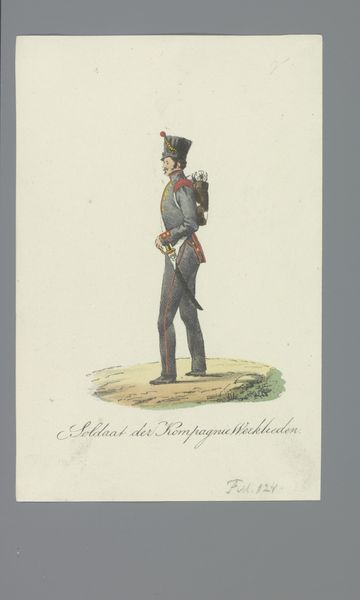

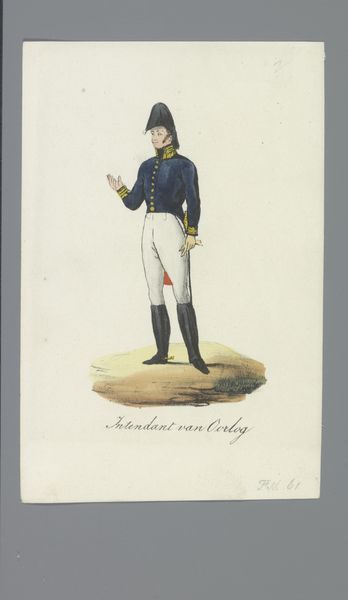

drawing, paper, ink, pencil

#

portrait

#

drawing

#

paper

#

ink

#

romanticism

#

pencil

#

costume

#

watercolour illustration

#

genre-painting

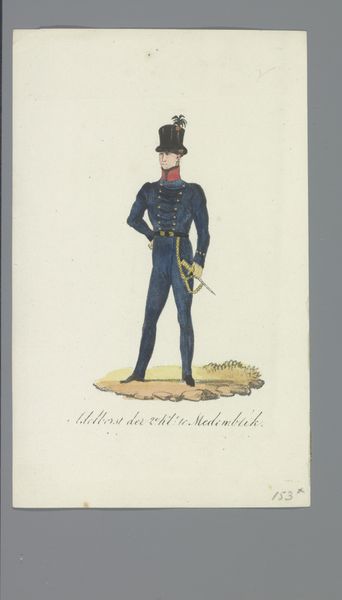

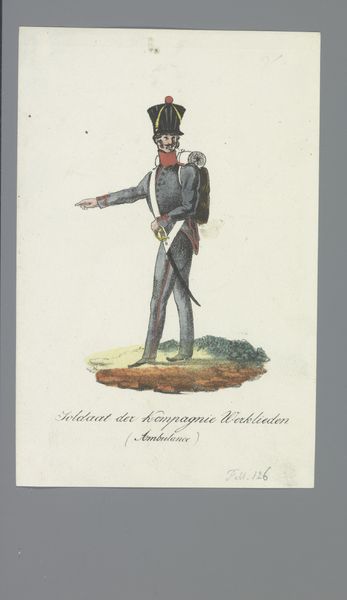

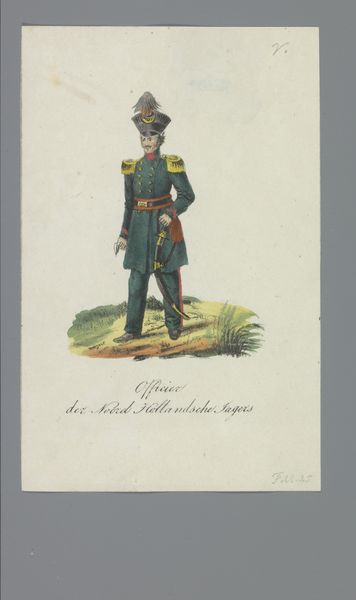

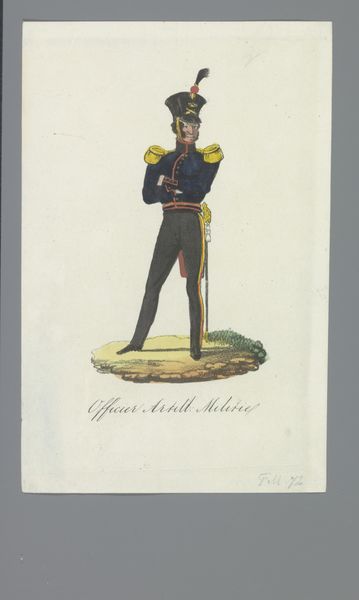

Dimensions: height 170 mm, width 110 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Editor: This is "Schutter Artillerist," a drawing made with pencil, ink, and watercolor on paper, sometime between 1835 and 1850 by Albertus Verhoesen. It's currently held at the Rijksmuseum. I’m really struck by the detail in his uniform – what else do you see in it? Curator: I’m drawn to consider the material conditions behind such depictions. This wasn’t just an image; it was a *product* – consider the social implications embedded in the procurement and crafting of the paper itself, and the pigments of the inks and watercolors, not to mention the economic position of someone who could commission such a piece. What kind of statement was this meant to make about the subject’s, and by extension, the commissioner's status? Editor: That’s a great point; I hadn't considered the paper itself as a marker of class. Do you think the choice of watercolor, ink and pencil was typical for depicting military figures at this time, and why? Curator: The relative accessibility of paper and these drawing materials, especially compared to the cost of oil paints, suggests that this portrait could have been targeting a market that falls outside the sphere of the super wealthy. The precision achievable with pen and ink, coupled with the delicate color washes allowed by watercolor, creates an image that balances aspirations of aristocratic portraiture with emerging middle-class tastes and consumer possibilities. What about the subject himself – an 'artillerist'. What labor went into becoming a member of this specific class of military? Editor: That’s interesting. Thinking about it that way really shifts my focus from just the image to all the labor that made this image possible, both on the part of the artist and his subject! Curator: Exactly! Looking at the drawing itself we tend to consider solely artistic choices, but placing this work within the matrix of 19th-century production and consumption tells a fuller and maybe more interesting story.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.