#

shape in negative space

#

negative space

#

white dominant colour

#

portrait reference

#

limited contrast and shading

#

animal drawing portrait

#

portrait drawing

#

tonal art

#

a lot negative space

#

remaining negative space

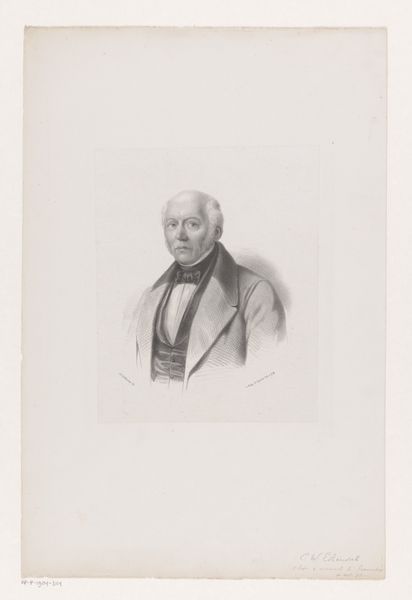

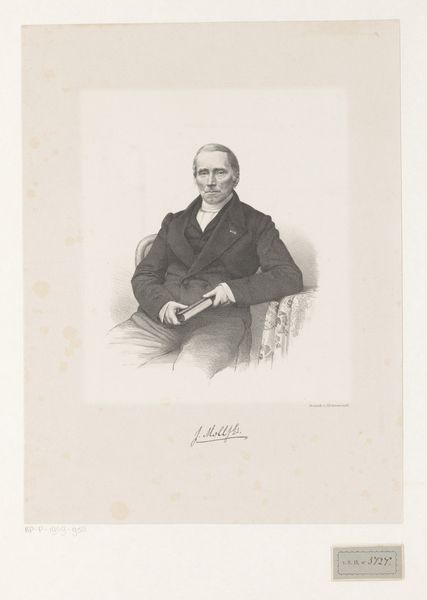

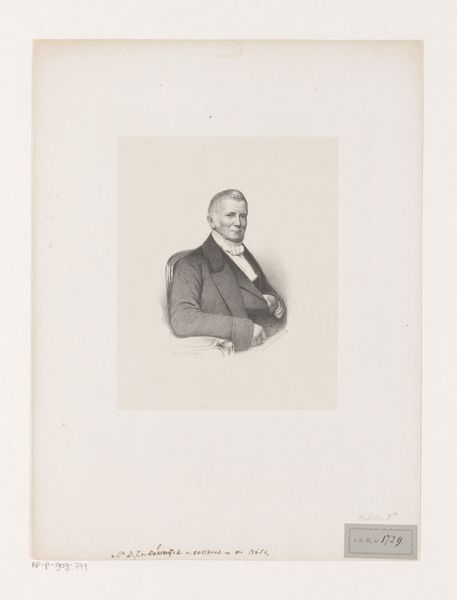

Dimensions: height 438 mm, width 300 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

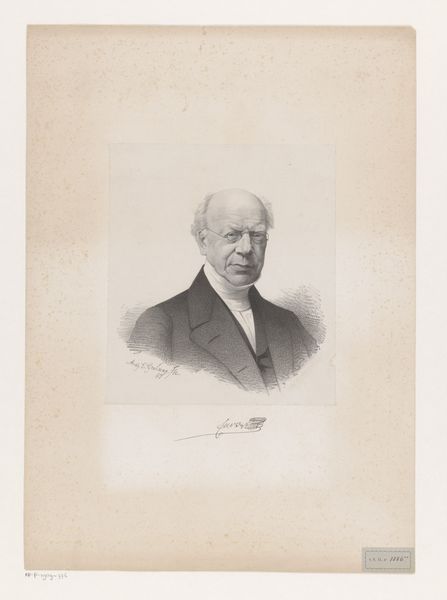

Curator: This is a portrait of Elisa Cornelis Unico van Doorn, an artwork attributed to Johan Hendrik Hoffmeister, likely created sometime between 1851 and 1883. It’s a striking example of tonal art. Editor: My initial reaction is…serenity, I think. The composition, with all that quiet, white space around him, it’s like he’s floating in a dream. A very composed, dignified dream. Curator: That's a lovely way to put it. The artist's careful use of negative space really isolates van Doorn, placing him in sharp focus. He commands attention without being ostentatious. What’s fascinating to me is what that blank space could represent, maybe a deliberate commentary on social class and visibility. Editor: I can see that. Is the emptiness supposed to represent privilege, that some individuals exist in a kind of protected sphere, untouched by the messiness of daily life? Or maybe the opposite—a commentary on the isolation and pressure felt by those in positions of power? Curator: Or maybe something more banal. Art production was expensive and artists economised as much as possible, sometimes resulting in unfinished-looking artwork such as this one. Editor: Potentially. But I would say there are plenty of other choices. Given the time period, mid to late 19th century, one must remember that this was the era of nascent photography. Think of those early portraits, staged and lit to mimic painting... Could this artist be using starkness, absence of setting, as a way of consciously setting his work apart, to assert the value of drawing as opposed to mechanical image production? To explore what it is about drawing that no photo could replicate? Curator: Ah, I see where you're going. It’s like Hoffmeister is emphasizing the *hand* in handmade, highlighting the skill and artistry involved. Every etched line, every shaded area declares "a human made this". And look at those eyes; the artist captures a particular sharpness. It is almost as if this drawing captures the essence of Mr. Van Doorn in a way a photo simply couldn’t. Editor: Precisely. We can see something here about personhood in the 19th century. Even something about Dutch society and its view of identity during the period that you wouldn’t be able to glean anywhere else. This may just be a portrait of a man but so much can be read from that drawing itself. Curator: It leaves me wondering about Van Doorn, what his story was. The drawing becomes a tantalizing glimpse into a life long past. Editor: Absolutely. And in the gaps, in what isn’t there, is just as revealing. We have a remarkable drawing to remind us of this fact.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.