Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

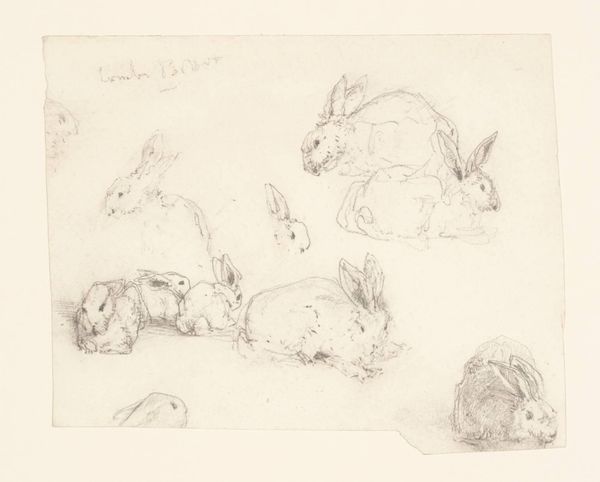

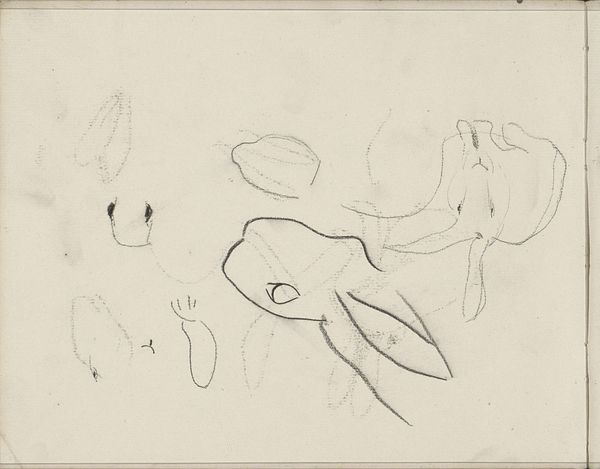

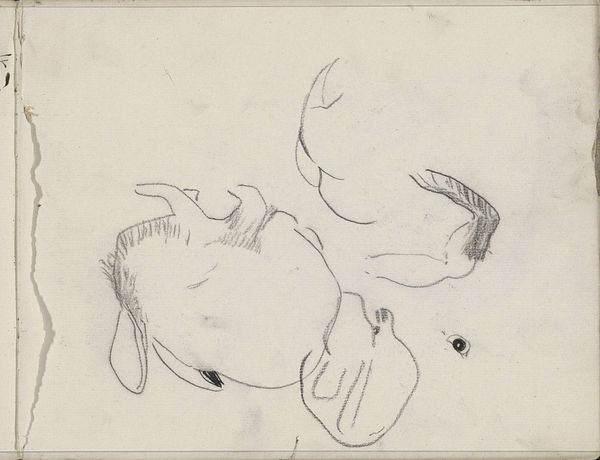

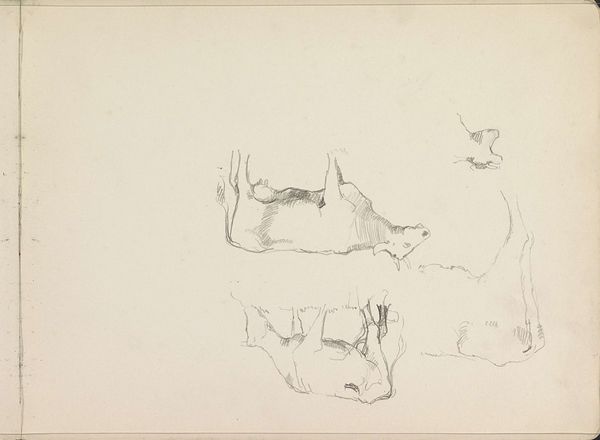

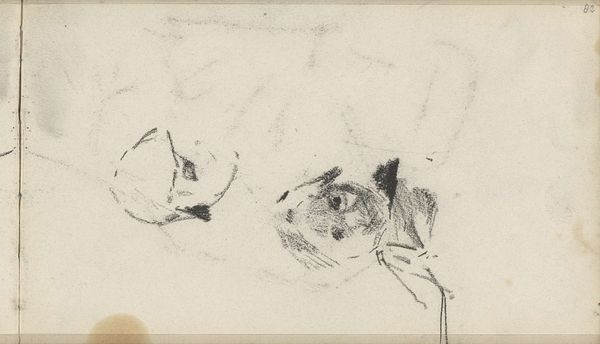

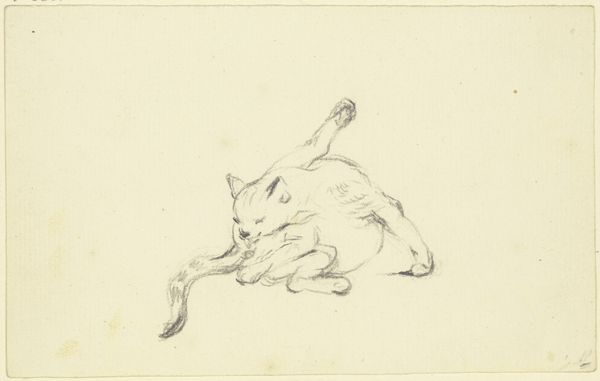

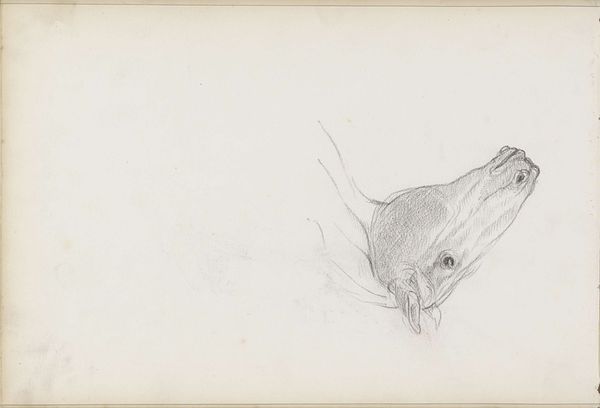

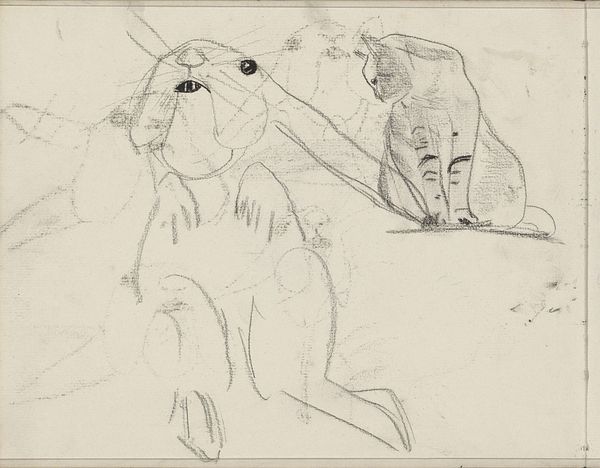

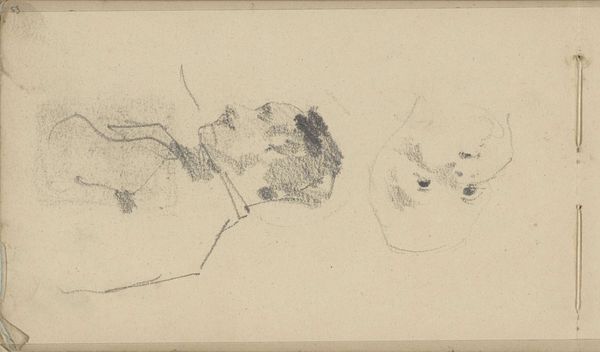

Editor: Here we have Carel Adolph Lion Cachet's "Konijnen," or "Rabbits," drawn in 1896, using pencil on paper. It looks like a quick sketch, almost like something from a personal sketchbook. What stands out to you about this piece? Curator: This unassuming sketch actually reveals much about the late 19th century’s changing attitudes towards art and the natural world. We see a deliberate shift away from academic rigidity toward capturing fleeting impressions, aligning with Impressionist ideals. What was the role of institutions like the Rijksmuseum during this shift? Did they embrace or resist this focus on sketching and works on paper? Editor: That's an interesting question. I suppose the establishment would have been hesitant at first. I wouldn't necessarily think that such a simple work would reflect so much about socio-political influences at the time. Curator: Exactly! Think about it: before photography became widespread, quick sketches like these often served scientific purposes, documenting animal anatomy. By presenting such a sketch as art, Cachet blurs the lines between science, art, and personal expression. Did this shift democratize art making, making it more accessible to the public? Editor: In a way, it feels like it did. Seeing the artist’s hand so clearly makes it feel more relatable. Curator: Precisely. And the display of this piece now at the Rijksmuseum contributes to the narrative of the evolving role of art institutions themselves. It raises questions about what gets valued, whose perspective is highlighted, and the shifting criteria for what constitutes "art." Editor: So it’s not just about rabbits, it's about how we've changed what art is for, who it's by, and who it's for. I wouldn't have guessed there were so many historical factors to consider. Curator: It all adds depth, doesn’t it?

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.