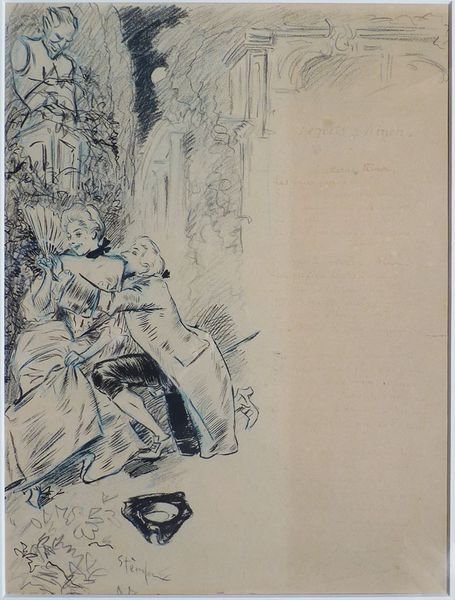

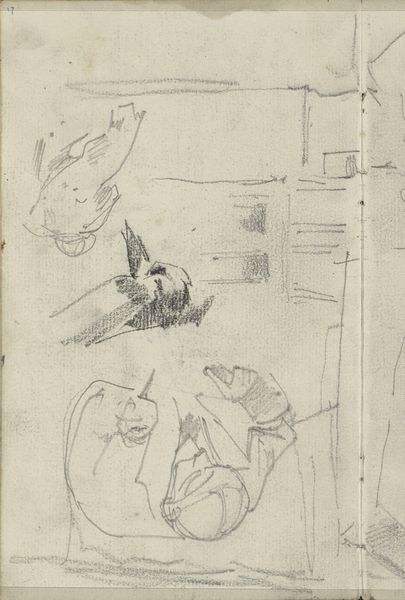

Dimensions: height 244 mm, width 154 mm

Copyright: Rijks Museum: Open Domain

Curator: Looking at "Street View with a Bridge," created around 1895 by Jan Hoynck van Papendrecht. It's a drawing executed in pencil. Editor: It feels… tentative. Like a half-remembered dream of a cityscape, quickly sketched before the details fade completely. Curator: I think that perfectly encapsulates the essence of Impressionism, its capturing of fleeting moments. Considering Papendrecht's background, predominantly known for his military art, this work seems like an interesting divergence. What are your thoughts about that switch, and maybe, does the bridge offer some commentary? Editor: Military art emphasizes precision, control, and, arguably, power structures. Shifting to something like this, loose and undefined, suggests a desire to perhaps represent vulnerability, transience… I hesitate to make too grand a claim, but a bridge is inherently a connector, a pathway across divides. Maybe that reflects a change in perspective for the artist. Was this at a point when war and imperialism were being called into question? Curator: Absolutely. The turn of the century witnessed a growing anti-war movement. I also can't help but think about the increasing urbanization during this time. These environments can represent not only connection and opportunity, but also alienation. The sketch's unfinished quality adds to this uncertainty; are we building, destroying, or simply observing? And more to the point, who is afforded such "observation" through what structures are these visual experiences consumed. Editor: That's a fascinating point, this 'unfinished' aspect. In that sense it evokes a sentiment in line with Walter Benjamin and even modern black and indigenous considerations. In a society which promotes completeness as some aspirational and almost mandatory point of cultural significance, the sketch and all of its implications provide an intriguing counterpoint. Curator: Precisely. And the choice of pencil as medium? Perhaps speaks to accessibility, or a deliberate subversion of traditional painting's authority. Editor: It does. In that, there's the chance of democratisation and inclusivity. Well, I hadn't considered it that way at first glance, but I appreciate how situating this seemingly simple drawing within larger historical and social contexts unlocks all sorts of potential meanings. Curator: That's what makes art history so engaging for me—unearthing those connections and letting them inform our present.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.