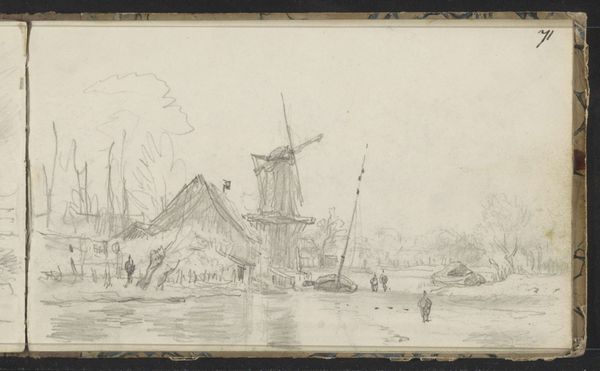

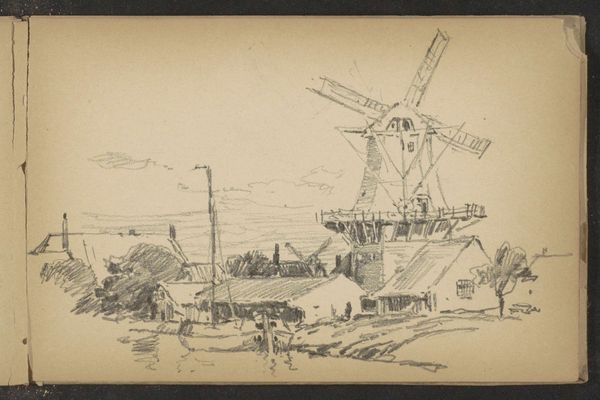

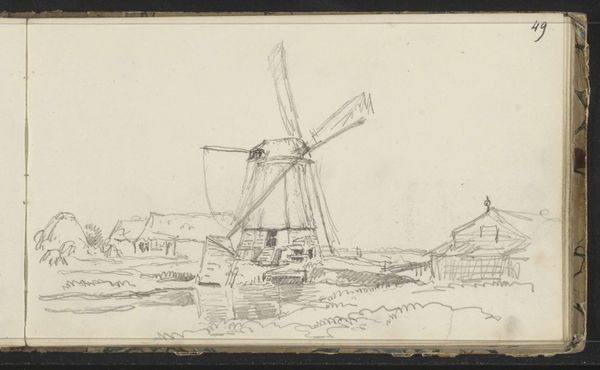

drawing, pencil

#

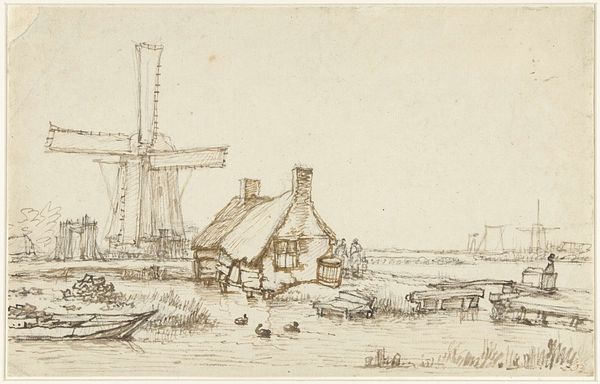

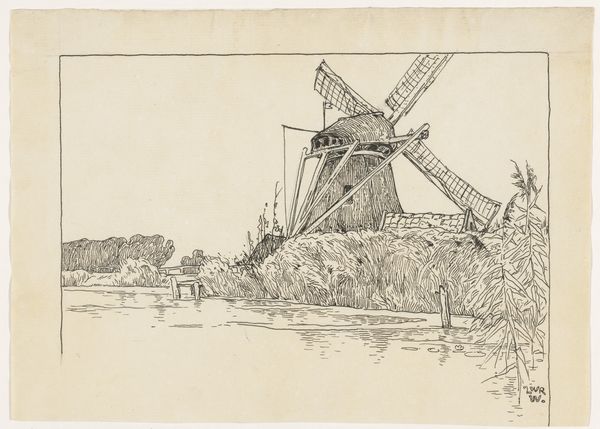

drawing

#

netherlandish

#

baroque

#

dutch-golden-age

#

landscape

#

form

#

pencil

#

line

#

realism

Copyright: Public Domain

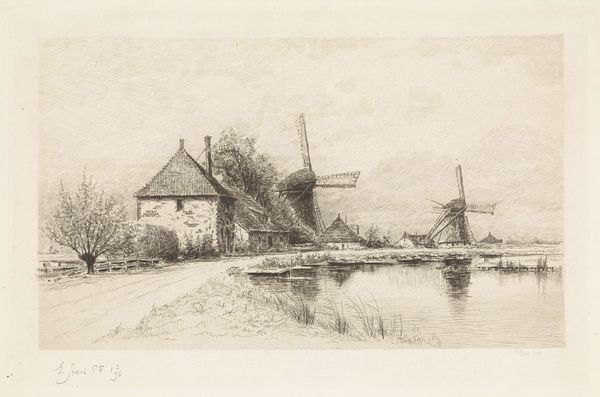

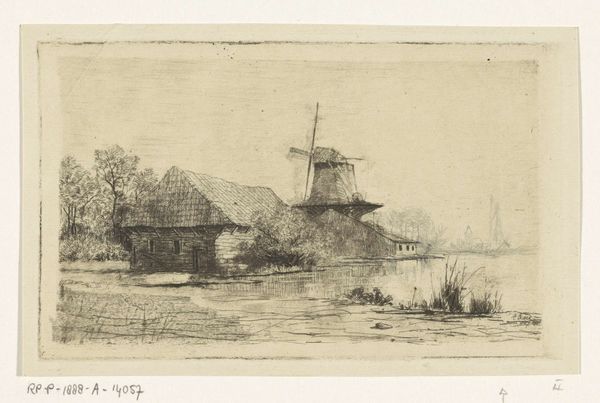

Curator: Jacob van Ruisdael’s “House and Windmill on the Bank of a Canal,” dating from around 1650, offers a glimpse into the Dutch Golden Age through a humble pencil drawing now held at the Städel Museum. Editor: Immediately, the drawing’s softness strikes me. It's incredibly subtle, almost a whisper of a scene, using delicate lines to construct depth and texture. The composition, though seemingly simple, invites the eye to wander across the canal and back. Curator: Ruisdael, a towering figure in Dutch landscape painting, here employs drawing to capture not just the appearance of the scene but, arguably, the very spirit of the Dutch countryside. Consider the symbolic weight of the windmill—an emblem of Dutch ingenuity and the ongoing battle against the waters. Editor: True, but the linear precision and gradations create form and also atmospheric perspective. The windmill and house are rendered with similar techniques that create a harmonious effect within the work. Semiotics might tell us something about those houses clustered in the distance too, although Ruisdael emphasizes those closest. Curator: Certainly. This drawing can also be interpreted through a postcolonial lens. The Dutch Golden Age was built on global trade, and these picturesque landscapes often romanticize a national identity that obscures the darker realities of colonialism and social stratification, with only some enjoying access to those landscapes depicted here. The canal and windmills made possible trade across networks to consolidate land ownership, in fact. Editor: An interesting point. Nevertheless, look closely at how Ruisdael employs light and shadow using simple, precise strokes. Notice the reflections on the water, the textured details of the thatched roof, and those open, shadowed, window frames. Curator: I agree, it’s undeniable that there's a stark contrast with his more idealized, often monumental, oil paintings of the period. But it’s perhaps through the depiction of ordinary life in this way, Ruisdael quietly communicates a sense of Dutch selfhood, one connected to land and labor, with complicated class relations. Editor: A complex view, and the contrast is undeniable, the stark simplicity also helps me view each architectural detail that brings form to the fore, that I’d gloss over otherwise. Thank you. Curator: And to you, it really allows for many entry points.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.