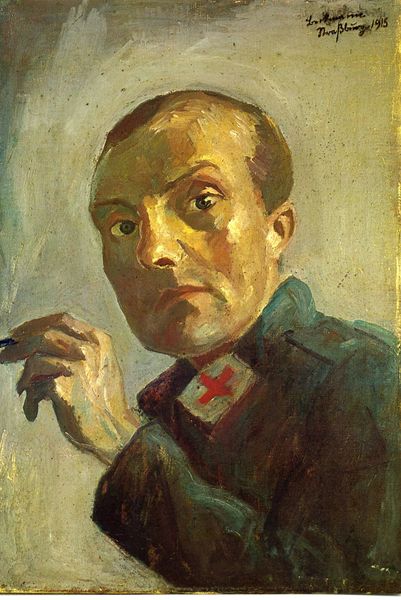

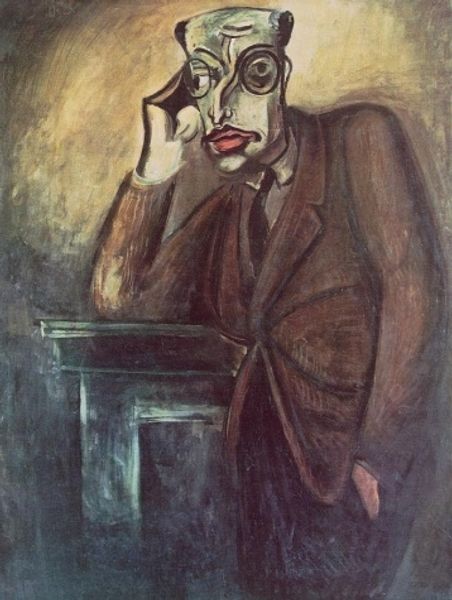

painting, oil-paint, oil

#

portrait

#

self-portrait

#

painting

#

oil-paint

#

oil

#

oil painting

#

expressionism

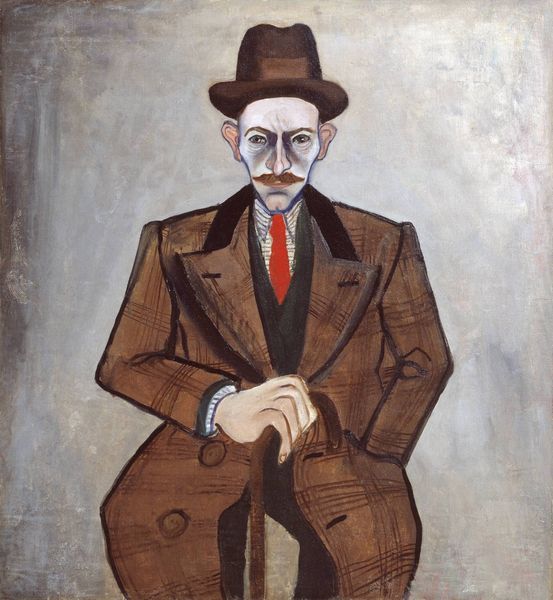

Dimensions: 65.0 x 55.5 cm

Copyright: Public Domain

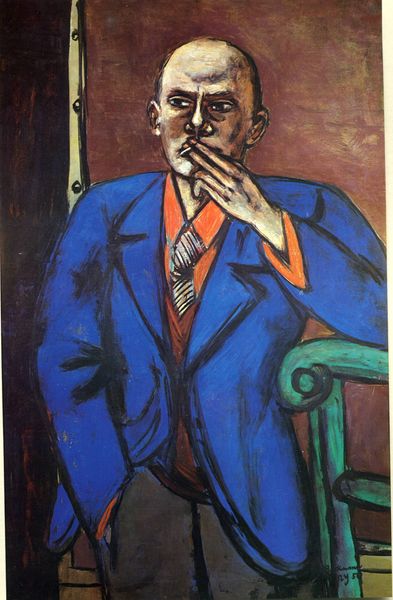

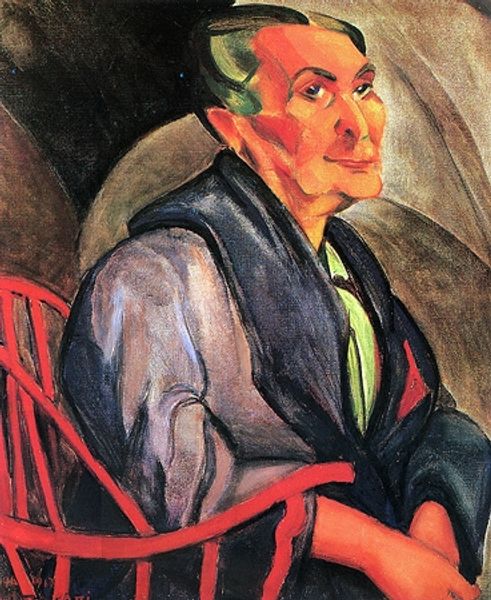

Curator: This is Max Beckmann's “Self-Portrait with Champagne Glass,” painted in 1919, now residing in the Städel Museum. Editor: Immediately, I’m struck by the somber mood, given the supposed celebratory context. The rigid composition and almost grotesque distortion of features create a sense of unease. Curator: Precisely. Beckmann's use of champagne becomes heavily symbolic here. In the aftermath of World War I, champagne becomes a symbol of the artist class in Germany struggling to express their psychological trauma; Beckmann lost many friends during the war and had a nervous breakdown from battlefield traumas. Editor: You see that in the painting's very structure, too. Note how Beckmann segments the composition. His body is boxed into the scene by a gaudy red curtain, another champagne reveler who looks like death himself, and a portrait behind him, evoking the many deaths of the past, but a fragile one: we can only see its ghostly form. The rigid shapes suggest that reality is splintering into shards, mirroring his psychological state. Curator: It’s as if he is surrounded by symbols of fleeting pleasure that are ultimately empty or even macabre in his world. The almost caricatured face behind him could represent societal superficiality or the ever-present specter of death looming after such immense loss. This makes him turn toward his own image within the painting as the most stable feature; it represents an attempt to gain inner stability. Editor: And that piercing gaze! His direct address—a typical strategy used in the composition of portraiture—is completely inverted here because he’s made the choice not to look joyous or inviting in his gaze. Instead, his cold eye invites viewers into the psychic experience of surviving death on an unimaginable scale. This tension within the semiotics of the self-portrait underscores that feeling of unease we spoke about. Curator: Absolutely. The champagne isn't celebratory; it’s almost like a mask or a way to self-medicate amidst a world steeped in post-war trauma, or more simply, a prop within the artist's repertoire as the man attempts to establish some feeling of mastery over death itself by adopting an almost godlike, but world-weary, status. Editor: It really makes you think about how artists can visually translate trauma into form and color. The painting is far more potent than any literal depiction of a war scene. Curator: For me, the self-portrait serves as a window into the profound emotional and cultural weight carried by artists like Beckmann, struggling to reconcile the past with an uncertain future, an invitation into what Adorno would have called “negative dialectics” toward the traumas of history. Editor: I'll certainly look at Beckmann’s work with renewed sensitivity, considering both his formal mastery and the symbolic weight he infuses into his canvases.

Comments

Join the conversation

Join millions of artists and users on Artera today and experience the ultimate creative platform.