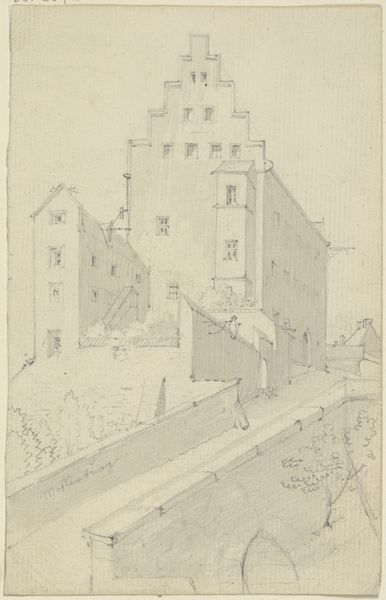

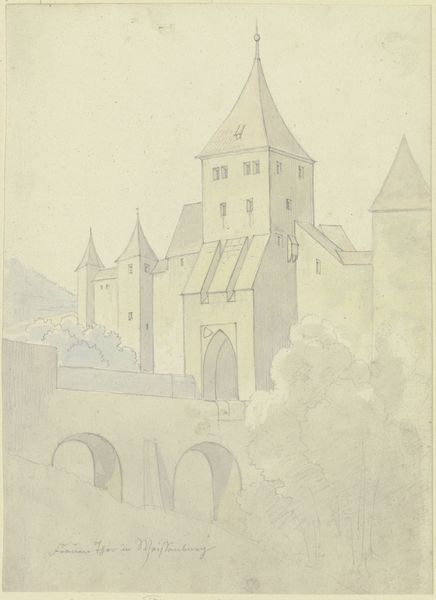

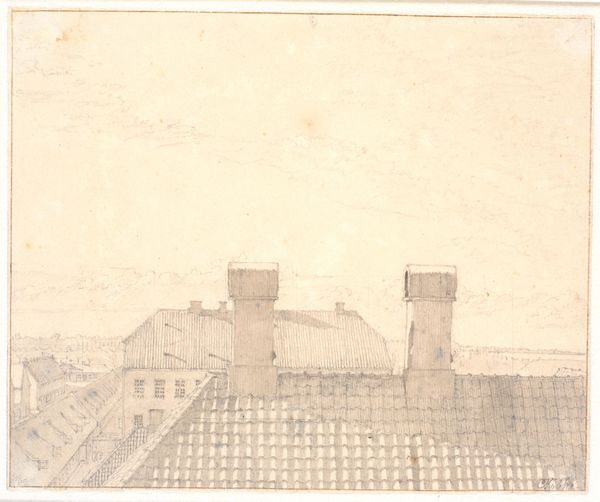

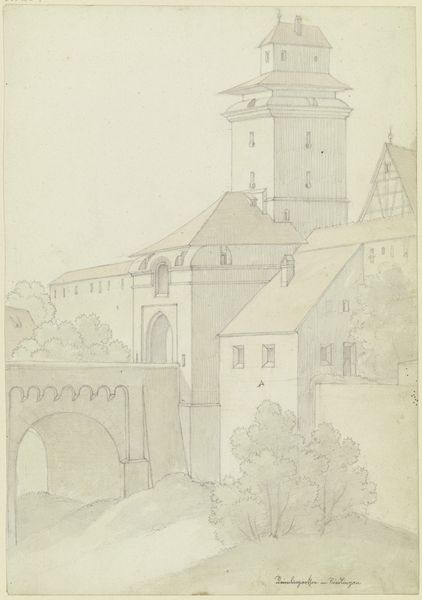

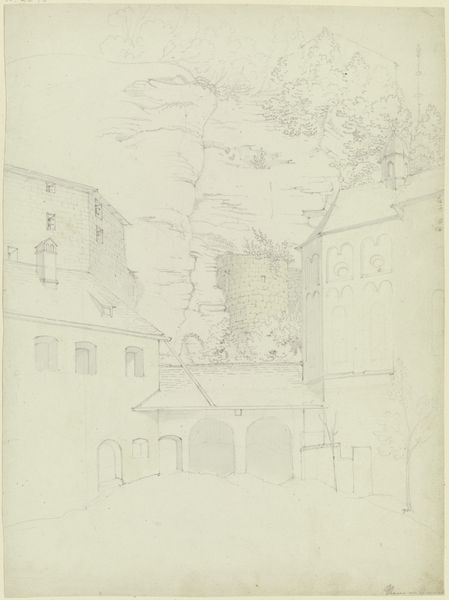

drawing, paper, ink, pencil, architecture

#

drawing

#

16_19th-century

#

landscape

#

paper

#

ink

#

pencil

#

architecture

Copyright: Public Domain

Editor: So, this is Karl Ballenberger's "At the Castle of Nuremberg," a drawing done with pencil, ink, and paper. It evokes a feeling of quiet observation, doesn’t it? What strikes me is how much detail there is in the stonework and architecture with seemingly basic tools, particularly on the towers. What do you see in this piece? Curator: What interests me most is the labour evident in Ballenberger's meticulous rendering of the stone walls and architectural elements, suggesting the role of architecture not only as a marker of power, but also a physical manifestation of human work, extraction, and consumption. Consider the procurement of materials, the masons shaping each block, the social structures required to erect such structures. Where was the paper made, and who made the inks used to trace such precise lines? Editor: That’s a fascinating perspective. I was focused on the artistic skill, but you're right, there's a whole network of labor embedded in the materials themselves. The extraction of stone, the forging of tools… It definitely changes how I see it. How would people in Ballenberger's time consider labor as related to the arts? Curator: In the 19th century, there was a growing separation between "high" art and craft. Academies valued painting and sculpture, often distancing those forms from the perceived "lower" status of decorative arts and manual trades. However, I'd argue that Ballenberger's drawing actively resists this separation, inviting us to consider the architectural process as itself an act of creative, skilled labor. Editor: That makes so much sense. It blurs the lines between art, architecture, and the effort required to construct the world around us. Seeing art as part of a wider socioeconomic process feels quite transformative. Curator: Exactly! Thinking about materiality and labour shifts our understanding, helping us recognize art not as isolated beauty, but as interwoven within social and material conditions. Editor: I never thought of it this way before. It’s more than just looking at pretty pictures; it's about understanding the human stories behind the creation. Curator: Precisely, and recognizing those hidden connections is central to appreciating the depth and complexity of art, like this seemingly simple drawing.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.