#

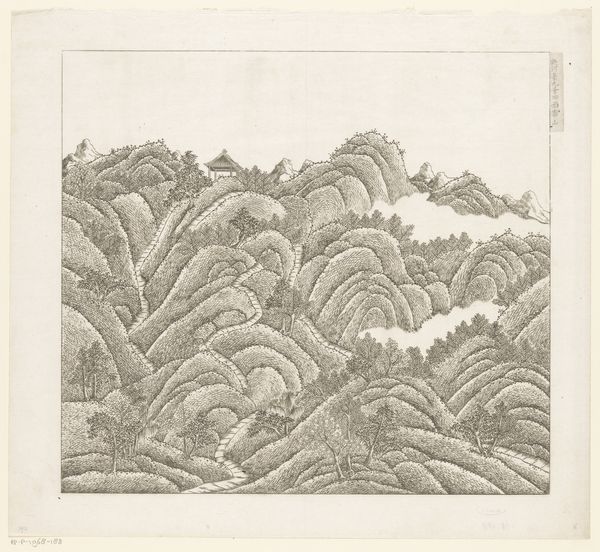

pencil drawn

#

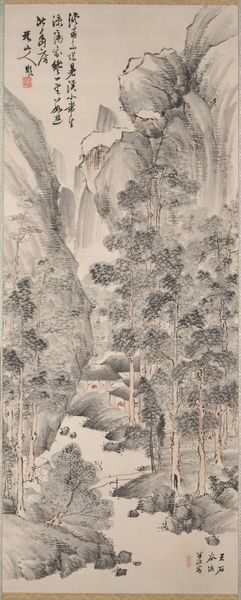

toned paper

#

light pencil work

#

pen sketch

#

pencil sketch

#

asian-art

#

old engraving style

#

landscape

#

pen-ink sketch

#

mountain

#

china

#

pen work

#

sketchbook art

#

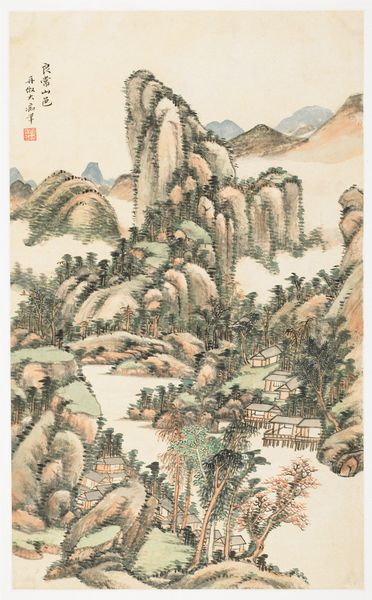

watercolor

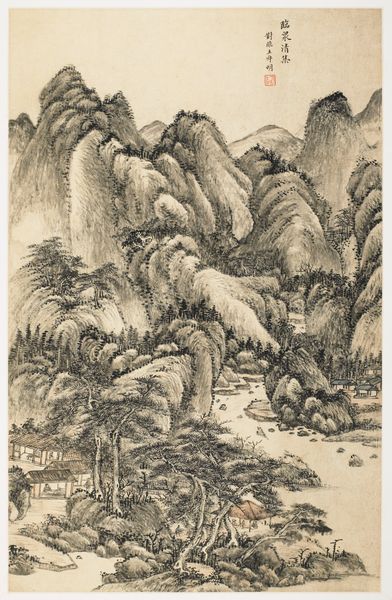

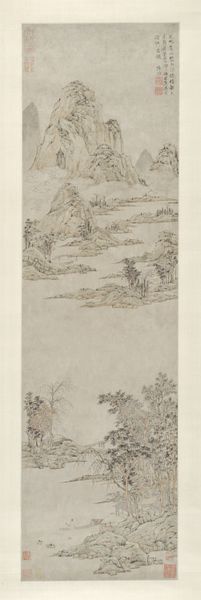

Dimensions: Image: 53 x 22 1/4 in. (134.6 x 56.5 cm) Overall with mounting: 87 3/4 x 28 1/4 in. (222.9 x 71.8 cm) Overall with knobs: 87 3/4 x 31 in. (222.9 x 78.7 cm)

Copyright: Public Domain

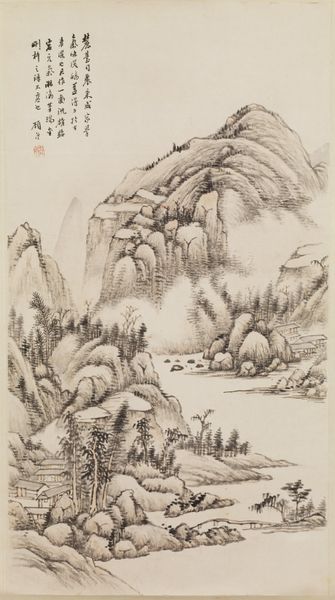

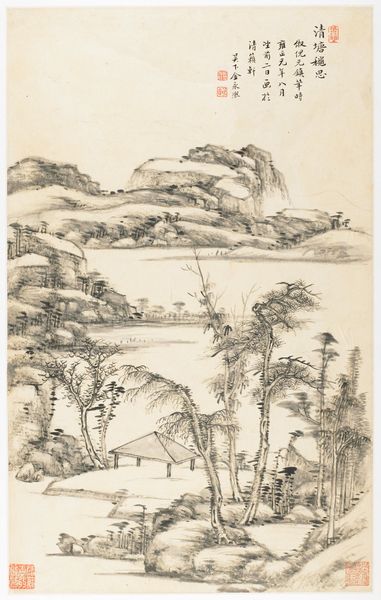

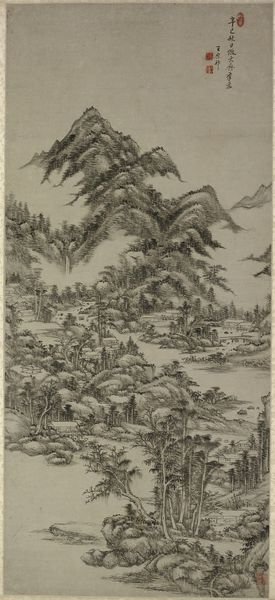

Curator: Immediately, the intricacy and delicate balance strikes me. The sheer level of detail achieved with what appears to be very fine pen work… there's a meditative quality. Editor: It's a landscape rendered in ink on paper, a piece titled "Landscape in the Style of Huang Gongwang," dating back to 1666. It was crafted by Wang Shimin, and it's now housed here at the Met. Considering the historical moment, I'm curious about its echoes of political and social upheaval. Curator: Ah, Huang Gongwang, one of the Four Masters of the Yuan Dynasty. It’s fascinating to see Shimin engaging with that artistic lineage so directly. The choice to emulate suggests a seeking of legitimacy and connection with an earlier golden age. Editor: Exactly! Looking at it through a contemporary lens, this act of artistic homage raises questions about cultural continuity during the Qing dynasty and the literati's response to the shift in power. The careful brushstrokes… Curator: Pen strokes actually, adding to its uniqueness in style that's much closer to a pen drawing that a watercolor technique. It feels different from typical brushstrokes used to describe paintings done using classical method, where the instrument is the "brush" and ink acts almost like watercolor. Editor: Well, whatever that stylistic decision evokes a deep sense of nostalgia for the past, particularly in landscape art. One could say there's a form of subtle resistance embedded in revisiting and revitalizing the values associated with an earlier dynasty. Curator: I see a world defined by scholar-officials. Mountains embody more than just geology, they stand as metaphors for the cosmic order and also reflect one’s aspiration towards philosophical wisdom. What about you? What symbols or meanings pop out? Editor: It is hard to ignore the calligraphy, inscribed with what seems like a formal poem at the top of the artwork... It’s both aesthetic and critical; the script, the composition, the mountain, the trees all function together like a system of cultural signs communicating privilege. I want to understand more about Wang Shimin's relationship to authority. Curator: The artistic skill evident in this imitation demonstrates how important it was for artists in 17th-century China to have a thorough awareness of the canon. It allowed Shimin to enter into conversation with the masters. Editor: Perhaps those mountains hold something other than an idyllic retreat; that's to say, by choosing this kind of landscape, artists weren’t really passive observers. Curator: Well, I now recognize, looking at it anew through your perspective, a visual representation of resilience; how artists continued exploring what defines beauty despite enormous upheaval. Editor: Agreed, that's why engaging art history through contemporary theory expands the picture—art objects, in our modern reality, become vehicles capable of generating conversations about gender, identity and race that may challenge established values in society, for example.

Comments

No comments

Be the first to comment and join the conversation on the ultimate creative platform.